Hollywood Palace, The

In 1963, ABC cleared two hours of Saturday night and refurbished a theater on Vine Street in Hollywood for a live Jerry Lewis talk show that was a spectacular and costly flop. Originally announced as a firm two-year deal, Jerry’s attempt was cancelled after 13 episodes, leaving the network with two problems: What to do with that two hours on Saturday night and what to do with that theater they’d purchased and rebuilt. They solved the second problem and half of the first by creating The Hollywood Palace, a one-hour variety show featuring the kind of vaudeville acts that had once placed the famed Palace Theater in New York. Though taped, the show strived for a “live” feel and acts were often recorded in one long, continuous take with little editing.

The host changed each week with Bing Crosby filling the post on the first show (January 4, 1964), the last (February 7, 1970) and twenty-eight other times in-between. Other frequent hosts were Milton Berle, Sid Caesar, Sammy Davis Jr. and Jimmy Durante. Durante was so popular on the show that after he hosted one that guest-starred The Lennon Sisters (December 5, 1967), ABC tried spinning-off a separate show, Jimmy Durante Presents the Lennon Sisters, which also taped at the Hollywood Palace. It didn’t last long. More successful was what happened after the one time Dean Martin hosted, which was the episode broadcast June 13, 1964. Both ABC and NBC offered him a weekly show, NBC won out and The Dean Martin Show went on the air in September of the following year.

Perhaps the most memorable episodes were the two hosted by Groucho Marx — 3/14/64 and 4/10/65. The latter featured the final performance of Margaret Dumont, re-creating a scene from the Marx Brothers film, Animal Crackers.

The top ticket above — for a taping on 2/22/64 — lists “Efram Zimbalist” as host. Actually, his name was Efrem Zimbalist Jr. and the following September, he became the star of an ABC series, The F.B.I. His Hollywood Palace episode, which aired a week after taping, featured comic actor Louis Quinn (who’d appeared with Zimbalist on 77 Sunset Strip), Kate Smith, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans with The Sons of the Pioneers, comedian Corbett Monica, comedy team Lewis and Christy, Alex Rix and his Trained Russian Bears, Adagio dancers Szony and Claire, and the famed high-wire act, The Great Wallendas.

The second ticket above, for an episode that aired May 22, 1965, featured host Tennessee Ernie Ford and his guests, Edie Adams, Ann Miller, comedian Jack Carter, acrobat Santos, The Gus Augspurg Monkeys and the O’Keffe comedy divers.

The third ticket is for an episode broadcast December 10, 1966. Host Jimmy Durante welcomed The Turtles, comedian George Carlin, actor Peter Lawford, singer Elaine Dunn, The Polack Brothers’ Elephants and two very famous acts. One was the great pantomime clown George Carl, not to be confused with Mr. Carlin. George Carl toured the globe with an act that no less than Johnny Carson once described as the funniest twenty minutes in the history of show business. It basically consisted of Carl attempting to perform a harmonica routine and getting himself hopelessly tangled in the microphone cord — one of those “you had to see it” routines. Also on the bill that evening at the Palace was Mrs. Miller, who had a brief, inexplicable career singing pop songs of the day, hopelessly out of style and key.

The fourth ticket is for the sixth season opener which aired 9/28/68 and featured host Bing Crosby, comedian Sid Caesar, folk singer Bob Gibson, jazz singer Abbey Lincoln and country-western singer Jeannie C. Riley and pop singer Bobby Goldsboro.

And the last ticket is for one that aired October 25, 1969 with host Englebert Humperdinck, comedian Jack E. Leonard, singer Nancy Ames, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Sid Caesar in a sketch with Maureen Arthur and Mickey Deems, and singer Lonnie Donegan.

One other performer deserves mention. At the end of each episode, that week’s host would read the list of who’d be performing on the stage the following week. The list was brought to him by the show’s “Billboard Girl,” an attractive model chosen for her poise and showgirl figure. For a while, it was a then-new actress named Raquel Welch. She went on to better things.

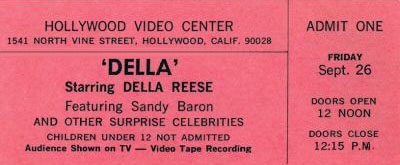

Della

In 1969, we had another one of those occasional periods when it seems like everyone with a S.A.G. card is getting to host a new talk show. Singer Della Reese’s was ballyhooed as the first one ever hosted by an Afro-American but it had more to recommend it than just that. She was a pretty good host and an awful lot of fine musical performers were enlisted to guest and to duet with Ms. Della. But actually, the best thing about the show was her co-host, comic Sandy Baron, who ably supplied whatever Reese couldn’t in the comedy department. They made a pretty good parlay and one of the industry trade papers later attributed the short run of Della to the fact that the field was then flooded with talk shows and there simply weren’t enough time slots for them all.

The best part of every episode was a segment at the end where Della, Sandy and that day’s guests would sit on stools and improvise short comedy scenes based on what were described as “suggestions from the audience.” Often in the world of improv comedy, that means that they had audience members write down some ideas which then went to someone who’d substitute pre-scripted premises…or maybe see if any of the audience submissions could be reworded slightly into one of the planned bits. I didn’t know much about improvisation in 1969 and since I recall those segments as being sometimes very funny, I wonder now if they were on the up-and-up. It’s certainly possible because Baron was the driving force in almost all of them and he was a very gifted comedian.

Baron was then on the rebound from the cancellation of Hey, Landlord!, a pretty funny sitcom he did for one season (1966-1967). A few years later, he would score a major success when he took over the role of Lenny Bruce in the Broadway play, Lenny. But failure was apparently more comfortable for Baron. It is said that the Lenny experience led to one of several mental breakdowns he was to suffer. Every time things were going well for him, friends observed, he’d go nuts, disappear and live as a homeless person for months. From time to time, he would surface again and often get some decent gig — Woody Allen hired him to be the on-camera narrator of most of Broadway Danny Rose — and then he’d crash-dive and submerge again. He developed chronic emphysema and the one time I met him, he was strapped to a portable oxygen tank. He was then living in a hotel thanks to some money he’d received as charity from acquaintances…but he was incapable of working and he said that when the funds ran out, he expected to go back out and live on friends’ couches and in the streets, oxygen tank and all. This was about two years before his death in 2001. I think acquaintances chipped in and kept him from sleeping in alleys for the rest of his life but still, it was a sad ending for someone who was once, albeit briefly, the hottest new comic in the business.

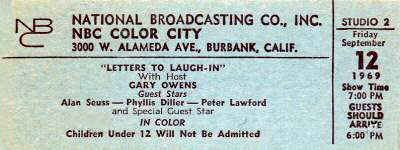

Letters to Laugh-In

Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In was a hit TV show that aired from January of 1968 to May of 1973. In September of ’69, its producers tried expanding their franchise into daytime with Letters to Laugh-In. This was back when each network’s daytime schedule was taken up with game shows and soap operas…and every year, someone would suggest, “Hey, maybe the housewives would like a change of pace.” There were several attempts to introduce comedy and/or variety into those line-ups and like Letters to Laugh-In, they didn’t last long. (The show it replaced, by the way, was the original Match Game. When Letters to Laugh-In failed to click, NBC replaced it with a soap opera, Somerset, which was a spin-off of another NBC soap opera, Another World.)

The host of Letters to Laugh-In was Gary Owens, who served as announcer of the prime-time show, and the premise was simple enough. Viewers were invited to send in their favorite jokes and each day, Gary and three guest performers would read selected jokes aloud. If your joke got read on the air, you received the tidy sum of $2.00 and there was a real prize if yours was selected as the best of the day. The worst joke won a trip to Beautiful Downtown Burbank. One of the three performers on each week of shows was a member of the prime-time cast. On the above ticket, the Laugh-In performer was Alan Sues, who apparently hadn’t been on the show long enough for the NBC ticket printers to know how to spell his name.

I recall it as a fun, fast-paced show that might have worked in another part of the day. One of the writers of the prime-time show, David Panich, was once asked about it. David said, “That was just a plot on the part of our cheap producers to establish that a joke was worth no more than two dollars.”

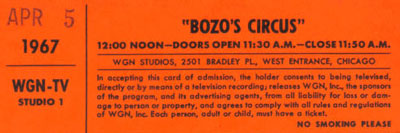

Bozo the Clown

Childrens’ records were big business in the forties and fifties, and some of the best were issued on the Capitol label. In 1946, a writer-producer for Capitol named Alan Livingston created the all-time superstar of the genre, Bozo the Clown, and issued the first of many records narrated by Bozo and chronicling his globe-spanning adventures. The material was cleverly-written with full orchestrations and the vocal talents of the original Bozo, Vance “Pinto” Colvig. The multi-talented Mr. Colvig had actually worked as a circus clown in his youth, but had more recently made his career as a cartoon writer and voice actor. He provided the sound of, among other great animated characters, Mr. Disney’s Goofy.

The Bozo records were a huge hit, leading to toys and merchandise, and to Colvig getting painted up in Bozo make-up for personal appearances. In 1949, he became one of the first TV personalities when he hosted a kids’ show on Los Angeles TV for a time. In the years following, other actors were recruited to play Bozo in a wide array of venues and one of them, Larry Harmon, came up with an idea. In 1956, together with a band of investors, he purchased the right to license and package Bozo TV shows across the country. Eventually, Harmon would acquire all rights to the World’s Most Famous Clown and build an industry around him.

The way it worked was that local TV stations throughout the U.S. would license the right to produce a Bozo show in their city, usually employing a local actor who would be properly trained by Harmon’s crew. He would don the rademarked clown make-up, and he’d play games with kids, do little comedy bits, and introduce the Bozo cartoons that Harmon’s animation company produced. The programs went under various names — Bozo’s Circus, Bozo at the Circus, Bozo’s Big Top, et al.

The two most notable franchise operations were on KTLA in Los Angeles, where Vance Colvig, Jr. (son of Pinto) stepped into his father’s oversized shoes from 1959-1964, and WGN in Chicago, where local producers pulled out all stops. Catering to an audience of both kids and adults, the WGN program began in 1961 and featured a live 13-piece band and top circus acts from around the world. A gent named Bob Bell was Chicago’s Bozo until ’84, whereupon comedian Joey D’Auria stepped into those immense shoes and kept folks laughing until the show finally ended in 2001. This ticket is from 1967, which was around the time the show hit its peak in popularity, even spawning a prime-time spin-off called Big Top. (Thanks to George Pappas of WGN for some corrections to this listing.)

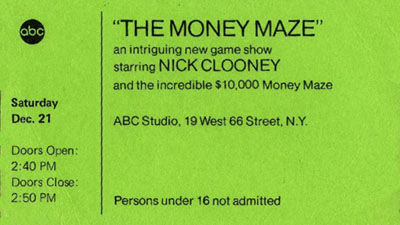

Money Maze, The

Nick Clooney is probably best known these days as a host on American Movie Classics and as the father of actor George Clooney. From 1974-1975, he was known as the host of The Money Maze, an ABC game show. (George worked on the staff of the program.)

It was kind of a dumb program, with couples competing for the right to challenge a huge maze that filled most of the studio. The husband would race through twists and turns in the labyrinth while his wife watched from an elevated platform called the Crow’s Nest, which gave her a view of the whole layout. She would yell out instructions — “Turn left! Turn right!” — while he tried to locate five “money towers.” These were pillars hidden in the maze which lit up when the husband pressed a button on them. One had a “1” on it; the rest had zeroes. If the hubby got all five towers lit and got out of the maze within 60 seconds, the couple won $10,000, which presumably made it all worth the effort. If he only lit the “1” tower and three zeroes, they got $1000. If he got the “1” and two zeroes, it meant $100, and I seem to recall at least one couple winning a big ten bucks. In order to win anything, the runner had to light the “1” tower and get out of the maze in the allotted time. During one phase of the show, the towers also had prize names on them; one represented a mink stole, another was a trip to Hawaii, etc.

Those of you interested in Trivial Connections might like to know that the producer of this series was the late Don Segall, whose career in TV and comic books I wrote about here. The director was Artie Forrest, who has directed as many TV shows as anyone who ever lived, most recently Whose Line Is It, Anyway? The announcer was Alan Kalter, who now works for David Letterman. And the show was under the aegis of Daphne Productions, which was Dick Cavett’s production company. Most likely, it got on the air because Cavett had received some sort of commitment from ABC as part of the contract for his late night talk show.

The show had a short run, in part because ABC was then having clearance problems with its late afternoon programming (it only ran in about half the country) but to a great extent because the set was so involved. Segall told me that it took a huge crew at least 24, sometimes 48 hours to set up the maze, which was rearranged for every tape day. At the time, there were only a few studios in New York that could accommodate it and they were in such demand that they charged a fortune in rental. Every time the producers of Money Maze went in to tape a new block of shows, they had to pay for several days of studio rental to set up, and then it cost an absurd amount in overtime to strike the set and store it away. Don described it as the first game show where the stage crew took home more money than the contestants.

It was a pretty clear ancestor of the so-called “reality shows” of today but don’t expect to see it on the Game Show Network. Word is that all but one or two of the tapes of Money Maze were erased, due either to neglect or the Clooneys paying someone off.

Concentration (1958-1973)

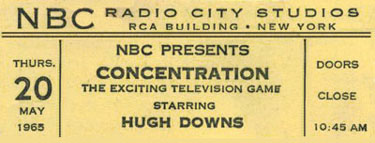

Hugh Downs was the announcer/sidekick on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show when NBC asked him to also host a daytime game show. It made for a long workday but Downs agreed and Concentration went on the air. It was a very simple game of memory, strategy and perception, and you won if you could uncover the pieces of a hidden rebus and solve it.

There was also a prime time version of Concentration in 1958 and 1961. At first, it was jazzed up with more lights and music, and Downs was ignominiously passed over for the moderator position, which went to Jack Barry who, with his partner Dan Enright, owned and produced the show. When ratings proved disappointing, NBC decided it needed Downs after all, and he agreed on the condition that they remove the “improvements.” This was done, he took over the nighttime version…and its ratings went up.

Downs was very proud and protective of the series. At a time when it was revealed that certain other game shows were rigged and their handlers — Jack Barry and Dan Enright — were being shamed out of the business, Downs happily pointed out that Concentration was practically rig-proof. Even if someone had given a contestant the answer, they couldn’t do much with it. If they solved the puzzle too early, they didn’t win much in the way of prizes. If they waited until the bounty grew to a hefty size, they risked losing control of the game board, which meant that their opponent would win. And at no point could the winnings equal the kind of megabucks that characterized the shows that were fixed. Nevertheless, Downs himself was known to skulk around and investigate to make sure the game he was fronting was as honest as he represented it to be. That honesty was one of the things that kept Concentration on the air for so long. When the game show scandals hit, NBC quietly bought out the interests of Barry and Enright, removed all mention of them from the show’s history, and kept things running.

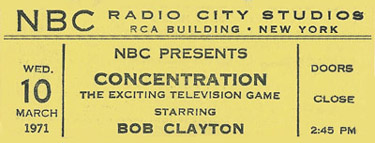

After Paar left The Tonight Show, Downs took over The Today Show…but he retained the Concentration job until 1969 when the workload got to be too much for him. When he announced his desire to quit the game show, the network asked him to stay on for an extra four months past the expiration of his contract to help them with an important ratings period. Downs agreed on the condition that the show’s announcer, Bob Clayton, be given the host’s job after him. Downs and Clayton were friends, and Clayton had filled in for Downs a few times and done the show the way Downs felt it should be done. As someone who had himself been typecast for a time as an off-camera announcer, Downs felt that Clayton was deserving of the on-camera gig, so he made the condition. NBC agreed and Clayton got the assignment…but not for long. Another Tonight Show sidekick, Ed McMahon, had been hosting Snap Judgment, another game show for NBC. When it was cancelled, Clayton was booted from Concentration and McMahon installed in his place. Downs was furious at the double-cross. Several months later, realizing McMahon wasn’t working out, an NBC executive actually phoned Downs and asked, “Do you know how we can reach Bob Clayton?” Downs later said he tried not to be too smug.

Clayton returned as emcee until the show was cancelled in 1973. Jack Narz hosted a syndicated revival that ran from 1973 to 1979 and then Alex Trebek hosted Classic Concentration, which ran from 1987 to 1991.

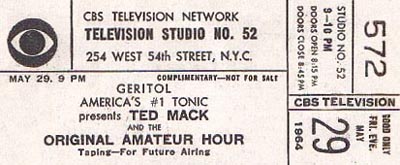

Original Amateur Hour, The

It always struck me as a little odd that everyone on Ted Mack’s show had talent except Ted Mack. I also don’t recall ever seeing anyone on that show whose talents, real though they may have been, seemed likely to lift them to any other spot in the great pantheon of show business. A few of the folks who appeared on The Original Amateur Hour later had careers but not because of that show. I mean, Robert Klein appeared on Mr. Mack’s show as part of a doo-wop group called The Teen-Tones, but that didn’t lead to a single job. Moreover, the success rate, given how long the show was on the air and how many talented amateurs it showcased, was amazingly low. How did it stay on the air, between radio and TV, for almost 40 years? I’d guess that the early part of the run had appeal because America was still climbing out of The Great Depression, and there was a certain thrill to listening to some poor kid get a chance to play his ocarina on radio and maybe, just maybe, get discovered and strike it rich.

But I can tell you what kept the show on the air its last decade or so, and the magic word is right there on the above ticket: Geritol. Its makers had discovered that certain kinds of shows were very good for selling their product. Today, one hears a lot about demographics and advertisers who seek a young audience. Geritol did the opposite: They wanted to reach people who might purchase “America’s #1 tonic,” which meant mostly older folks. To that end, they sponsored a number of shows — Lawrence Welk’s being the prime example — even when the overall ratings weren’t grand. Today, a network might refuse the business (as ABC eventually cancelled Welk, despite Geritol’s wishes) on the grounds that a couple of older-skewing shows can drag down the rest of the schedule. But back then, individual sponsors had more clout, especially over certain time slots. So Ted Mack stayed on, despite a lack of talent or, at times, much of an audience.

Chicken Soup

In the late eighties, comedian Jackie Mason made a comeback of sorts with a one-man show that played Broadway and theaters around the nation. Entitled, The World According to Me, it was kind of a “best of” of stand-up material he’d been performing for several decades and it was very funny. ABC grabbed him up for a situation comedy that debuted on September 12, 1989 under the name, Chicken Soup. As you can see from the first ticket above, they were taping in May without having settled on that name.

On Chicken Soup, Mason played Jackie Fisher, a single Jewish man who stumbles into an odd relationship with an Irish-Catholic widow with three children. Lynn Redgrave played the widow and critics were almost unanimous in remarking how unconvincing the stars were as a couple. It was difficult to imagine the on-screen Jackie Mason being in love with anyone but certainly not Ms. Redgrave. Never have the co-stars of a situation comedy seemed so remote from one another. Only when the scripts allowed Mason to sneak in a bit of his stand-up style did the series show any life. But that didn’t happen often enough for the show to survive and it only ran eleven episodes.

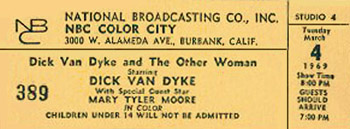

Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman

In 1969, with their film careers not going quite the way they wanted, Dick Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore reunited for an hour of songs and sketches themed around the various aspects of dating and marriage. Critics raved about Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman and audiences loved it. It led to offers for both Dick and Mary to return to series television and soon after, Mary was working on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. And a year after that made a hit, Dick Van Dyke was doing The New Dick Van Dyke Show.

Mary Tyler Moore Hour, The

A few years after The Mary Tyler Moore Show ended its historic run, Mary decided she not only wanted to be back on television but to venture into the then-dying field of variety programming, Her first attempt (titled simply Mary) was a quick failure, yanked from the airwaves before it could do irreparable damage to her stardom. A year later, she was back with a new format that tried to split the difference between variety and a situation comedy. On The Mary Tyler Moore Hour, she played TV star Mary McKinnon, who was engaged in the business of starring in a weekly variety series. Most weeks, the storyline involved securing a couple of guests to appear on her program and within the framework of that scenario, there was ample opportunity to sing, dance and do sketches. But it all felt forced and contrived, and no one was too happy with the result.

A writer who worked on the show once told me that among the reasons that its makers gave for the failure was that Mary felt out of place. Even though they surrounded her with friends (like Nancy Walker), she still would have been happier if they could have done the show at the facility at Radford. Unfortunately, that studio was still primarily film and did not seem to have an available stage suitable for a big variety show. The venue was probably not a major reason for the show not working but it seems to have been at least a tiny contributing factor. (Bob Newhart stuck to the same building when he attempted to follow his hit MTM sitcom.)