Rhoda

Valerie Harper appeared in (and darn near stole) the first episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1970 and many thereafter. Her Jewish, agonizingly-single character of Rhoda Morganstern provided a nice contrast to Mary’s white bread niceness. And after veteran character actress Nancy Walker began appearing occasionally to play Rhoda’s mother, you had another sitcom just waiting to happen. Finally, in 1974, it spun off on its own, largely under the creative direction of writer-producers Lorenzo Music and David Davis.

Harper and Walker were at the center of it all, joined by Julie Kavner as Rhoda’s younger sister, Harold Gould as her father, and a number of characters who were probably intended as regulars but didn’t stick around long. This included David Groh, who played a man who wooed and eventually wed the title character. Though the wedding episode drew monster ratings, the show lost a great deal of its edge with a married Rhoda. Eventually, they separated and the show never quite regained its pre-marital momentum. In all, it lasted five seasons.

The most interesting character on the show, and maybe the most popular, was never seen. It was Carlton, the perpetually-inebriated doorman of the building in which Rhoda lived — a man heard primarily over that building’s intercom. He did make a few on-camera appearances but something always got in the way, preventing the audience (and even Rhoda) from seeing his face. Carlton was so popular that when Rhoda got married, the producers made sure the newlyweds made their new home in the same apartment house. (One of those producers, Mr. Music, provided the voice of Carlton. In 1980, Carlton was finally seen — in the pilot for what was intended as a weekly, prime-time animated program, Carlton, Your Doorman. The one episode produced won an Emmy as that year’s Best Animated Special but failed to become a series.)

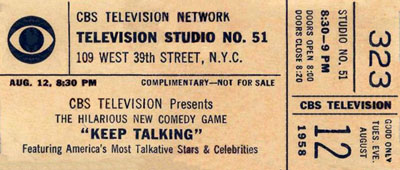

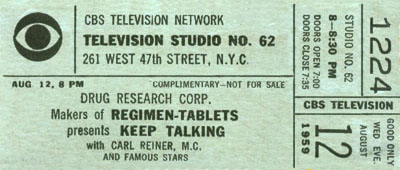

Keep Talking

Keep Talking was a prime-time game show that ran from 1958 to 1960. Each week, two teams would compete, each team composed of three celebrities. The rules changed from time to time but basically, the idea was to keep a story going with the panelists handing it off each time a bell rang, improvising wildly. Somewhere in there, they had to incorporate a secret word and the other panel had to guess the word…and as I recall from my vague memories, no one cared all that much about the scoring. The fun was in how one panelist would take the story off in some odd direction and then the next would have no idea what to do with it. Frequent players included Paul Winchell, Danny Dayton, Morey Amsterdam, Peggy Cass, Pat Carroll, Orson Bean, Audrey Meadows and Elaine May.

The show went on the air in July of 1958 and its first host was Monty Hall, a Canadian who was then fairly new to American TV. He was replaced in October because, if we believe his autobiography, the comedians on the show were complaining about him making funny remarks and competing with them. This seems unlikely, especially since his replacement was Carl Reiner, who was probably funnier than anyone on the panel. When Reiner left to do other things, Merv Griffin took over for the final season.

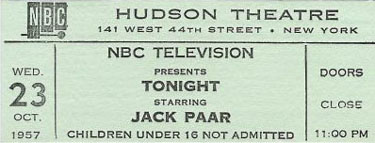

Tonight (1957-1962)

Steve Allen hosted his final episode of Tonight on January 25, 1957. The following Monday, NBC debuted a new multi-hosted, “magazine” show in the time slot…Tonight: America After Dark. It was an instant flop and they hurriedly began searching for someone who could do a new version of Tonight more like the old version. The logical choice might have been Ernie Kovacs, who’d hosted two nights a week during the final months of Allen’s run…but Kovacs was off in Hollywood appearing in movies and therefore unavailable. Instead, they picked Jack Paar, who had hosted a dizzying array of short-lived programs for all the networks in the preceding years. He took over NBC’s late night time slot on July 29, 1957.

The early Paar Tonight program was a mess. At one point before its debut, someone at NBC got the brilliant idea that it should consist of three separate game shows. Each night, the contestant who won the first would move on to appear on the second…and so forth. This notion was discarded, in part because America After Dark was sinking fast and there wasn’t the time to develop three new game shows. So they went with the idea of conversation/chat show but even then, NBC wanted to save a tiny amount of money by booking guests a week at a time — the same people for five nights in a row. This too was discarded but for the initial weeks, Paar struggled to make conversation with eccentric guests in whom he had no interest. Further souring the proceedings was the man selected as Paar’s sidekick, veteran comic actor Franklin Pangborn. Pangborn had been funny in scripted film parts but on a live, ad-lib show he was a disaster.

For several months, Paar teetered on the brink of cancellation but then everything miraculously came together. Pangborn was eliminated and eventually, the show’s announcer — Hugh Downs — expanded his role to full sidekick status. And Paar found his style and the right kind of guest to have on. He soon had a whole stock company of recurring visitors that included Alexander King, Oscar Levant, Dody Goodman, Jonathan Winters, Peter Ustinov, Hans Conried, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Elsa Maxwell, Cliff “Charlie Weaver” Arquette and Peggy Cass.

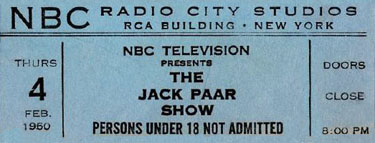

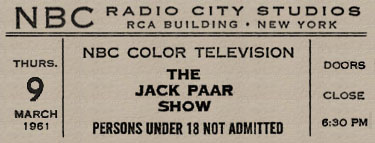

In these tickets, one can see things changing. Paar didn’t like staying up late — he once said he’d never watch his show if he hadn’t been on it — so when taping became more practical, it went from a live show to one recorded earlier and earlier in the evening. For some reason, as they moved it earlier, they decided to raise the minimum audience age from 16 to 18.

But the big change was in the name. Few recall that there were a few years there when Tonight ceased to exist and it became just The Jack Paar Show, though many people, Paar included, continued to refer to it as “The Tonight Show,” which technically had not yet been its name. It was just Tonight. As you can see from the above ticket for 2/4/60, it was The Jack Paar Show then. Exactly one week later — 2/11 — Paar did his famous on-air resignation because the network had censored an innocuous joke about a “water closet” and what he said when he quit for several weeks was, “I’m leaving The Tonight Show.” Before that, there had also been a brief interim period when its title had been Jack Paar Tonight. (Paar’s unsuccessful attempt to return to the format in 1973 would be called Jack Paar Tonite.) In Paar’s final months, NBC did all it could to get the word “Tonight” back into promotions and TV Guide and to pretend that that had been the name all along.

Paar did his final show in the time slot on March 30, 1962, and the show was handed over to guest hosts for six months to await the arrival of Johnny Carson. After a brief hiatus, he returned to NBC with a shorter but largely identical weekly prime time series called The Jack Paar Program that ran until 1965.

Tonight (1954-1957)

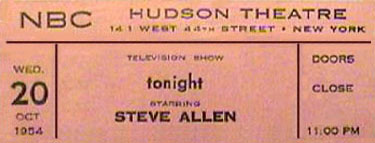

In 1954, NBC exec Sylvester “Pat” Weaver was looking for a show that could open up the late night time slot for network programming. He’d previously tried a raucous variety show there — Broadway Open House, hosted some nights by Morey Amsterdam and others by Jerry Lester. This time, his search led him to The Steve Allen Show, which the New York NBC station had recently begun airing. That show was acquired, retitled and expanded…and it debuted on September 27, 1954 as Tonight! Histories note that the exclamation point was soon deleted…and we can see there is none on the earliest ticket above, which is from October 20.

Tonight did everything it could to fill the time: There were games, interviews, sketches, songs…even, for a brief time, a nightly (real) news round-up. Steve played piano, chatted with eccentric guests and audience members and put up with stunts which he sometimes described as “plots by the staff against my life.” Gene Rayburn was the announcer and sidekick, Skitch Henderson led the band and the regulars included singers Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Pat Marshall and Andy Williams. Allen also developed a “stock company” of talented comedians like Don Knotts, Louis Nye, Tom Poston and Dayton Allen, though some of these didn’t join him until his post-Tonight ventures.

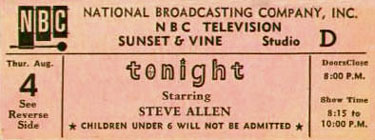

Most of the time, as the above tickets show, Tonight came from the Hudson Theater in New York. The one ticket above for a broadcast from the West Coast is for August 4, 1955. For eight weeks that year, Tonight emanated from Hollywood where Steve Allen was filming the title role in the movie, The Benny Goodman Story. Most performers would consider it a tiring full-time job to either host a late night show five evenings a week or to star in a major motion picture. Somehow, without missing a day on either, Allen managed to do both…though right after, he did take his first two-week vacation from Tonight, turning the festivities over to guest host Ernie Kovacs.

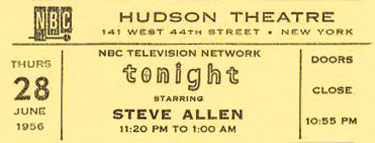

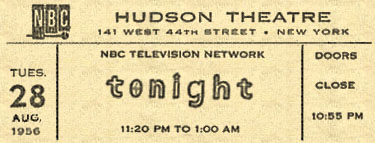

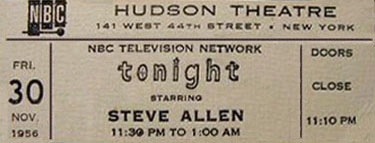

The August 28, 1956 ticket lacks the name of Steve Allen because it was for a Tuesday night. In June of that year, Allen and his crew had added a prime-time Sunday night series to their workload, competing on NBC against Ed Sullivan’s popular CBS program. The burden became too great and soon after, the Monday and Tuesday night broadcasts of Tonight were turned over to a roster of ever-changing guest hosts, including Ernie Kovacs, Jack Paar, Henry Morgan, Bill Cullen, Gene Rayburn, Rudy Vallee, Tony Randall, cartoonist Al Capp and even, from the old Broadway Open House, Morey Amsterdam and Jerry Lester. It is not known who was hosting on the eve of the above ticket, but Kovacs became the regular Monday-Tuesday host in October.

He continued, with Allen hosting the rest of the week, until the end of January, 1957 when Allen decided to give up the late night show. The entire thing was replaced by a famous disaster — a multi-hosted “magazine” show called Tonight: America After Dark. When that didn’t work, they went scurrying to find another single host who could do something more like what Steve Allen had done. The result was the Jack Paar era of Tonight.

The Steve Allen years remain legendary but largely lost: As with many shows of the day (including the Tonight run of Paar and the early years of his successor, Johnny Carson) few tapes or kinescopes exist. Allen went on to do more shows, some of which were in a similar enough format that many people remember them when they think they’re remembering his years on Tonight. This can get you to wondering if the lost shows are legendary in part because they are lost, and are appraised only through rose-colored memories. Judging from what does exist — and from those later shows — that’s not the case here. Steve Allen’s Tonight does seem to have been as unpredictable, spontaneous and innovative as everyone remembers…the kind of show you dared not miss because the next day, everyone would be saying, “Did you see what happened on that show last night?” Talk shows aren’t like that anymore. They don’t have anyone as brave and as willing to soar before millions without controls and preparation as was Steve Allen.

We do have a mystery with these tickets. Every single history of Tonight says that for its entire run, the Steve Allen version was an hour and 45 minutes in length, commencing at 11:15 PM in the East. Yet here, we see that the 6/28/56 and 8/28/56 tickets give an airtime of 11:20 PM to 1:00 AM, and the 11/30/56 ticket says 11:30 PM to 1:00 AM. If there’s an explanation for this, I’d love to hear it.

Steve Allen Show, The (1953-1954)

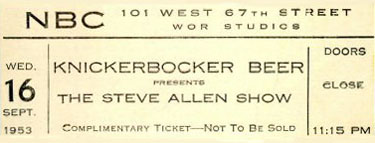

In 1953, the local NBC station in New York was WNBT and its late night movie program was getting clobbered by a better package of films being broadcast every night on the CBS affiliate, WCBS. Knickerbocker Beer, which was then a major brand, decided it wanted to sponsor something else on WNBT…say, a variety show. Ted Cott, a successful radio executive who had recently moved into television at the NBC affiliate, suggested Steve Allen as host.

Histories say that Allen debuted in the Fall of ’53 with a 45 (or 40 in some accounts) minute program every night called The Knickerbocker Beer Show, and that after thirteen weeks, its name was changed to The Steve Allen Show. The above ticket suggests that the name change came much more rapidly than that.

Done at first without writers and always without much of a budget, Allen’s local show was an immediate success, garnering both critical acclaim and the desired higher (than WCBS) ratings. On it, Allen would play the piano, chat with audience members or guests or sidekick-announcer Gene Rayburn, bring on Steve Lawrence and/or Eydie Gorme to sing a song — the bandleader was Bobby Byrne — and basically lay the foundation for talk shows to come. Less than a year later, most of the operation would be moving over to do a network show called Tonight.

Hollywood Palace, The

In 1963, ABC cleared two hours of Saturday night and refurbished a theater on Vine Street in Hollywood for a live Jerry Lewis talk show that was a spectacular and costly flop. Originally announced as a firm two-year deal, Jerry’s attempt was cancelled after 13 episodes, leaving the network with two problems: What to do with that two hours on Saturday night and what to do with that theater they’d purchased and rebuilt. They solved the second problem and half of the first by creating The Hollywood Palace, a one-hour variety show featuring the kind of vaudeville acts that had once placed the famed Palace Theater in New York. Though taped, the show strived for a “live” feel and acts were often recorded in one long, continuous take with little editing.

The host changed each week with Bing Crosby filling the post on the first show (January 4, 1964), the last (February 7, 1970) and twenty-eight other times in-between. Other frequent hosts were Milton Berle, Sid Caesar, Sammy Davis Jr. and Jimmy Durante. Durante was so popular on the show that after he hosted one that guest-starred The Lennon Sisters (December 5, 1967), ABC tried spinning-off a separate show, Jimmy Durante Presents the Lennon Sisters, which also taped at the Hollywood Palace. It didn’t last long. More successful was what happened after the one time Dean Martin hosted, which was the episode broadcast June 13, 1964. Both ABC and NBC offered him a weekly show, NBC won out and The Dean Martin Show went on the air in September of the following year.

Perhaps the most memorable episodes were the two hosted by Groucho Marx — 3/14/64 and 4/10/65. The latter featured the final performance of Margaret Dumont, re-creating a scene from the Marx Brothers film, Animal Crackers.

The top ticket above — for a taping on 2/22/64 — lists “Efram Zimbalist” as host. Actually, his name was Efrem Zimbalist Jr. and the following September, he became the star of an ABC series, The F.B.I. His Hollywood Palace episode, which aired a week after taping, featured comic actor Louis Quinn (who’d appeared with Zimbalist on 77 Sunset Strip), Kate Smith, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans with The Sons of the Pioneers, comedian Corbett Monica, comedy team Lewis and Christy, Alex Rix and his Trained Russian Bears, Adagio dancers Szony and Claire, and the famed high-wire act, The Great Wallendas.

The second ticket above, for an episode that aired May 22, 1965, featured host Tennessee Ernie Ford and his guests, Edie Adams, Ann Miller, comedian Jack Carter, acrobat Santos, The Gus Augspurg Monkeys and the O’Keffe comedy divers.

The third ticket is for an episode broadcast December 10, 1966. Host Jimmy Durante welcomed The Turtles, comedian George Carlin, actor Peter Lawford, singer Elaine Dunn, The Polack Brothers’ Elephants and two very famous acts. One was the great pantomime clown George Carl, not to be confused with Mr. Carlin. George Carl toured the globe with an act that no less than Johnny Carson once described as the funniest twenty minutes in the history of show business. It basically consisted of Carl attempting to perform a harmonica routine and getting himself hopelessly tangled in the microphone cord — one of those “you had to see it” routines. Also on the bill that evening at the Palace was Mrs. Miller, who had a brief, inexplicable career singing pop songs of the day, hopelessly out of style and key.

The fourth ticket is for the sixth season opener which aired 9/28/68 and featured host Bing Crosby, comedian Sid Caesar, folk singer Bob Gibson, jazz singer Abbey Lincoln and country-western singer Jeannie C. Riley and pop singer Bobby Goldsboro.

And the last ticket is for one that aired October 25, 1969 with host Englebert Humperdinck, comedian Jack E. Leonard, singer Nancy Ames, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Sid Caesar in a sketch with Maureen Arthur and Mickey Deems, and singer Lonnie Donegan.

One other performer deserves mention. At the end of each episode, that week’s host would read the list of who’d be performing on the stage the following week. The list was brought to him by the show’s “Billboard Girl,” an attractive model chosen for her poise and showgirl figure. For a while, it was a then-new actress named Raquel Welch. She went on to better things.

Della

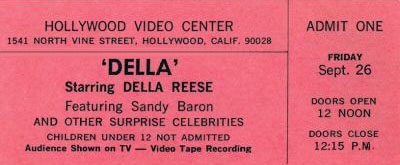

In 1969, we had another one of those occasional periods when it seems like everyone with a S.A.G. card is getting to host a new talk show. Singer Della Reese’s was ballyhooed as the first one ever hosted by an Afro-American but it had more to recommend it than just that. She was a pretty good host and an awful lot of fine musical performers were enlisted to guest and to duet with Ms. Della. But actually, the best thing about the show was her co-host, comic Sandy Baron, who ably supplied whatever Reese couldn’t in the comedy department. They made a pretty good parlay and one of the industry trade papers later attributed the short run of Della to the fact that the field was then flooded with talk shows and there simply weren’t enough time slots for them all.

The best part of every episode was a segment at the end where Della, Sandy and that day’s guests would sit on stools and improvise short comedy scenes based on what were described as “suggestions from the audience.” Often in the world of improv comedy, that means that they had audience members write down some ideas which then went to someone who’d substitute pre-scripted premises…or maybe see if any of the audience submissions could be reworded slightly into one of the planned bits. I didn’t know much about improvisation in 1969 and since I recall those segments as being sometimes very funny, I wonder now if they were on the up-and-up. It’s certainly possible because Baron was the driving force in almost all of them and he was a very gifted comedian.

Baron was then on the rebound from the cancellation of Hey, Landlord!, a pretty funny sitcom he did for one season (1966-1967). A few years later, he would score a major success when he took over the role of Lenny Bruce in the Broadway play, Lenny. But failure was apparently more comfortable for Baron. It is said that the Lenny experience led to one of several mental breakdowns he was to suffer. Every time things were going well for him, friends observed, he’d go nuts, disappear and live as a homeless person for months. From time to time, he would surface again and often get some decent gig — Woody Allen hired him to be the on-camera narrator of most of Broadway Danny Rose — and then he’d crash-dive and submerge again. He developed chronic emphysema and the one time I met him, he was strapped to a portable oxygen tank. He was then living in a hotel thanks to some money he’d received as charity from acquaintances…but he was incapable of working and he said that when the funds ran out, he expected to go back out and live on friends’ couches and in the streets, oxygen tank and all. This was about two years before his death in 2001. I think acquaintances chipped in and kept him from sleeping in alleys for the rest of his life but still, it was a sad ending for someone who was once, albeit briefly, the hottest new comic in the business.

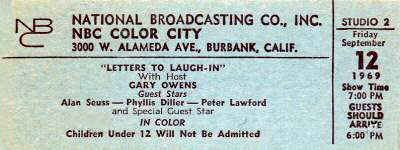

Letters to Laugh-In

Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In was a hit TV show that aired from January of 1968 to May of 1973. In September of ’69, its producers tried expanding their franchise into daytime with Letters to Laugh-In. This was back when each network’s daytime schedule was taken up with game shows and soap operas…and every year, someone would suggest, “Hey, maybe the housewives would like a change of pace.” There were several attempts to introduce comedy and/or variety into those line-ups and like Letters to Laugh-In, they didn’t last long. (The show it replaced, by the way, was the original Match Game. When Letters to Laugh-In failed to click, NBC replaced it with a soap opera, Somerset, which was a spin-off of another NBC soap opera, Another World.)

The host of Letters to Laugh-In was Gary Owens, who served as announcer of the prime-time show, and the premise was simple enough. Viewers were invited to send in their favorite jokes and each day, Gary and three guest performers would read selected jokes aloud. If your joke got read on the air, you received the tidy sum of $2.00 and there was a real prize if yours was selected as the best of the day. The worst joke won a trip to Beautiful Downtown Burbank. One of the three performers on each week of shows was a member of the prime-time cast. On the above ticket, the Laugh-In performer was Alan Sues, who apparently hadn’t been on the show long enough for the NBC ticket printers to know how to spell his name.

I recall it as a fun, fast-paced show that might have worked in another part of the day. One of the writers of the prime-time show, David Panich, was once asked about it. David said, “That was just a plot on the part of our cheap producers to establish that a joke was worth no more than two dollars.”

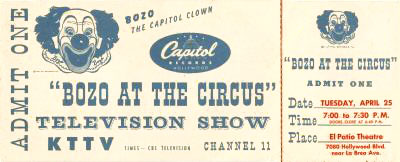

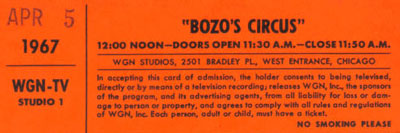

Bozo the Clown

Childrens’ records were big business in the forties and fifties, and some of the best were issued on the Capitol label. In 1946, a writer-producer for Capitol named Alan Livingston created the all-time superstar of the genre, Bozo the Clown, and issued the first of many records narrated by Bozo and chronicling his globe-spanning adventures. The material was cleverly-written with full orchestrations and the vocal talents of the original Bozo, Vance “Pinto” Colvig. The multi-talented Mr. Colvig had actually worked as a circus clown in his youth, but had more recently made his career as a cartoon writer and voice actor. He provided the sound of, among other great animated characters, Mr. Disney’s Goofy.

The Bozo records were a huge hit, leading to toys and merchandise, and to Colvig getting painted up in Bozo make-up for personal appearances. In 1949, he became one of the first TV personalities when he hosted a kids’ show on Los Angeles TV for a time. In the years following, other actors were recruited to play Bozo in a wide array of venues and one of them, Larry Harmon, came up with an idea. In 1956, together with a band of investors, he purchased the right to license and package Bozo TV shows across the country. Eventually, Harmon would acquire all rights to the World’s Most Famous Clown and build an industry around him.

The way it worked was that local TV stations throughout the U.S. would license the right to produce a Bozo show in their city, usually employing a local actor who would be properly trained by Harmon’s crew. He would don the rademarked clown make-up, and he’d play games with kids, do little comedy bits, and introduce the Bozo cartoons that Harmon’s animation company produced. The programs went under various names — Bozo’s Circus, Bozo at the Circus, Bozo’s Big Top, et al.

The two most notable franchise operations were on KTLA in Los Angeles, where Vance Colvig, Jr. (son of Pinto) stepped into his father’s oversized shoes from 1959-1964, and WGN in Chicago, where local producers pulled out all stops. Catering to an audience of both kids and adults, the WGN program began in 1961 and featured a live 13-piece band and top circus acts from around the world. A gent named Bob Bell was Chicago’s Bozo until ’84, whereupon comedian Joey D’Auria stepped into those immense shoes and kept folks laughing until the show finally ended in 2001. This ticket is from 1967, which was around the time the show hit its peak in popularity, even spawning a prime-time spin-off called Big Top. (Thanks to George Pappas of WGN for some corrections to this listing.)

Money Maze, The

Nick Clooney is probably best known these days as a host on American Movie Classics and as the father of actor George Clooney. From 1974-1975, he was known as the host of The Money Maze, an ABC game show. (George worked on the staff of the program.)

It was kind of a dumb program, with couples competing for the right to challenge a huge maze that filled most of the studio. The husband would race through twists and turns in the labyrinth while his wife watched from an elevated platform called the Crow’s Nest, which gave her a view of the whole layout. She would yell out instructions — “Turn left! Turn right!” — while he tried to locate five “money towers.” These were pillars hidden in the maze which lit up when the husband pressed a button on them. One had a “1” on it; the rest had zeroes. If the hubby got all five towers lit and got out of the maze within 60 seconds, the couple won $10,000, which presumably made it all worth the effort. If he only lit the “1” tower and three zeroes, they got $1000. If he got the “1” and two zeroes, it meant $100, and I seem to recall at least one couple winning a big ten bucks. In order to win anything, the runner had to light the “1” tower and get out of the maze in the allotted time. During one phase of the show, the towers also had prize names on them; one represented a mink stole, another was a trip to Hawaii, etc.

Those of you interested in Trivial Connections might like to know that the producer of this series was the late Don Segall, whose career in TV and comic books I wrote about here. The director was Artie Forrest, who has directed as many TV shows as anyone who ever lived, most recently Whose Line Is It, Anyway? The announcer was Alan Kalter, who now works for David Letterman. And the show was under the aegis of Daphne Productions, which was Dick Cavett’s production company. Most likely, it got on the air because Cavett had received some sort of commitment from ABC as part of the contract for his late night talk show.

The show had a short run, in part because ABC was then having clearance problems with its late afternoon programming (it only ran in about half the country) but to a great extent because the set was so involved. Segall told me that it took a huge crew at least 24, sometimes 48 hours to set up the maze, which was rearranged for every tape day. At the time, there were only a few studios in New York that could accommodate it and they were in such demand that they charged a fortune in rental. Every time the producers of Money Maze went in to tape a new block of shows, they had to pay for several days of studio rental to set up, and then it cost an absurd amount in overtime to strike the set and store it away. Don described it as the first game show where the stage crew took home more money than the contestants.

It was a pretty clear ancestor of the so-called “reality shows” of today but don’t expect to see it on the Game Show Network. Word is that all but one or two of the tapes of Money Maze were erased, due either to neglect or the Clooneys paying someone off.