That Was the Week That Was

That Was the Week That Was was an acclaimed but short-lived satiric show in England then again in America. The British version went on the air in November of 1962 and went off at the end of ’63. One of its last episodes was among its most memorable: A shortened episode that paid tribute to John F. Kennedy shortly after his assassination. The audio from it was released as a record album and it remains one of the few relics of that live show. Other weeks, it was songs and sketches about what was happening in the world with David Frost as its host.

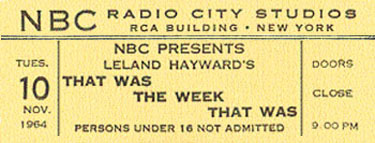

The pilot for an Americanized version aired in this country on November 10, 1963. Ratings were soft but critics raved about the show which was also headed up by David Frost and which started his rise to fame in the U.S. A weekly version commenced on January 10, 1964. Frost, commuting from the U.K., continued to host or at least dominate the proceedings. Nancy Ames was the “TW3 Girl,” singing the title and closing song which each week featured new and topical lyrics. The rest of the cast changed from week to week but at times included Henry Morgan, Alan Alda, Mike Nichols & Elaine May, Elliot Reid, Buck Henry and many more. For a half hour, they’d talk about items in the news and parody whatever there was to parody.

There were two other notable contributors though you didn’t see much of either on screen. Comedy songwriter Tom Lehrer wrote tunes, many of which he later recorded and put out as an album entitled That Was the Year That Was. And puppeteer Burr Tillstrom, best known for the kids show Kukla, Fran & Ollie invented a new art form with what he called “Hand Ballets.” They were little vignettes set to music in which Tillstrom used his bare hands as puppets and would mime some in-the-news situation. The most memorable one was an interpretation of the Berlin Wall. One of Tillstrom’s hands played the wall; the other represented a person who lived in East Berlin and who was in agony about being separated from his family on the other side of the wall/hand.

TW3 was a modest success in America and NBC kept it on the air expecting that it would draw extra attention during the ’64 Presidential Campaign. What they hadn’t reckoned with was this: It was then relatively easy and not all that expensive for a political candidate to buy a half-hour or even an hour of prime-time TV time. Most of the candidates did that, often pre-empting regular programming with little advance notice. You’d tune in to see your favorite show and discover it was not on and a political ad was in its place. The Republican National Committee took to buying the time slot for That Was the Week That Was, over and over just to keep it off the air and stifle its somewhat-liberal viewpoints. This was a special problem for TW3 as it was done live, and material written for one week was often out-of-date and unusable a few weeks later. Often, they would write and rehearse for several days and then find out that the show would not be airing; that a special touting Barry Goldwater for President would air instead. By the time TW3 did air again, it had lost its mojo and whatever steady viewers it had. It ended in May of ’65.

The ticket above is to a live broadcast that probably did air since it was one week after the election. Leland Hayward, who got billing over the title on tickets and some other places, was a show business entrepreneur who bounced back and forth between being an agent and a producer. His most notable work was on Broadway where he “produced” (i.e., put together the deals for) shows like Mister Roberts, Gypsy and The Sound of Music. His main contribution to That Was the Week That Was was probably just getting it on the air.

Arthur Murray Party, The

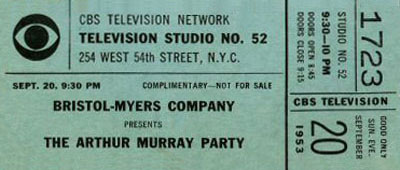

Arthur Murray was the founder and figurehead of a chain of studios that would teach you to dance, thereby making you more attractive and popular. The Arthur Murray Party was a weekly show that was basically an infomercial before that term was invented. Each week, Arthur and his wife Kathryn hosted a big party filled with instructors from his schools who would dance together and with guest stars, making it all look so fun and easy.

The series started in 1950 on ABC, the moved to the DuMont Network, then back to ABC, then over to CBS and continued to rebound between networks, NBC included, until it finally went off in 1960. Its form was often parodied as was the stiffness of his host, who was often compared to Ed Sullivan. But it entertained a lot of people and probably sold them a lot of dance lessons.

Sammy Davis Jr. Show, The

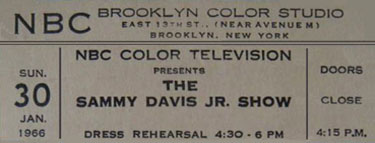

The weird part about The Sammy Davis Jr. Show is how often Sammy wasn’t on it. Sammy had been a frequent guest on other variety shows and specials and hosted a few, all to great success so NBC arranged to give him his own show. The first show aired on January 7, 1966 and got tepid reviews despite a guest list that included Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, Nancy Wilson, Corbett Monica, the dance team of Augie & Margo, and The Will Mastin Trio. Davis himself was reportedly unhappy with the show.

Then the next three weeks, guest hosts filled in for Sammy. Months earlier, he had taped a variety special for ABC that had not been aired. When the network finally scheduled it, they reminded Davis of a clause in his contract that said that he would not appear on any other TV program for three weeks preceding the broadcast of the special. NBC and Davis were furious and accused ABC of slotting the show in a deliberate effort to sabotage his new series. That was probably the idea but it worked. Sammy Davis Jr. had to stay off The Sammy Davis Jr. Show for three weeks which were hosted, one per week, by Johnny Carson, Sean Connery and Jerry Lewis. Davis used that time to work on future shows and to try and revamp the format. It helped a lot and the show got better when he returned to it but the momentum was gone…or something. It was cancelled and the last episode — a one-man show with just Sammy — aired on April 22.

The last three or four episodes of the 15 episodes were produced after the cancellation notice. They were looser with more ad-libbing and Sammy booked guests that he wanted on the show as opposed to guests he was told would help the ratings. Many TV critics thought the series had finally found itself and urged NBC to give it another chance but that didn’t happen. There was talk of another network picking it up but that didn’t happen either. Sammy did a lot of television but didn’t have his own series again until his 1975 talk show, Sammy & Company, which was notorious for how much its guests fawned over each other.

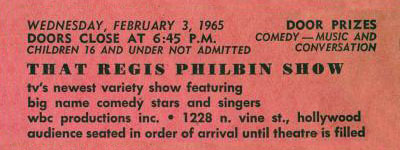

That Regis Philbin Show

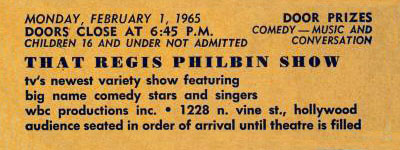

Regis Philbin got his start in broadcasting as a writer for the local news at KCOP TV in Los Angeles. His first on-air opportunity came at a station in San Diego and that’s where he was offered his own talk show. Steve Allen had been doing a syndicated show for the Westinghouse Broadcasting Company and when it went off in 1964, Westinghouse hired Philbin, moved him back to L.A. and offered That Regis Philbin Show to the many stations that had been programming The Steve Allen Show. Some took it, some didn’t…and then those that did began dropping it and That Regis Philbin Show ended in three or four months (accounts differ). Philbin bounced around between small TV and radio jobs until April of 1967 when he was hired as the sidekick on The Joey Bishop Show which ran late night on ABC and which was done from the same building as Philbin’s failed syndicated series. It was the first of many comebacks for the man who would eventually log more hours on television than anyone else.

Al Jarvis Show, The

Al Jarvis (1909-1970) was one of the first radio disc jockeys in Los Angeles and one of the first to start doing television. Starting around 1947 and continuing through the fifties, he usually had a daily radio program and a daily TV show. The radio one was usually Make-Believe Ballroom and the TV one was either a dance party show, a talk show or some combination of the two forms. The above ticket is from 1952 when he was broadcasting on KECA-TV, which was then the name of the L.A. ABC affiliate. Ob February 1 of 1951, KECA switched over to become KABC.

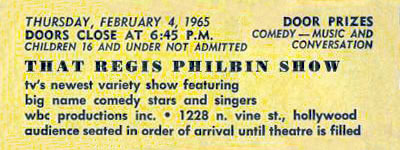

That’s Life

That’s Life was an extremely original and daring concept in TV: An hour-long ongoing sitcom and musical comedy that each week featured songs (some written for the show, some not) and dances. Robert Morse was the star and the show had something of the feel of his hit, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He played a young man named Robert Dickson while E.J. Peaker played his new wife, Gloria Quigley.

Each week, we got another chapter of their evolving life together, and there were guest stars aplenty. Among those who appeared, sometimes more than once as recurring characters, were Ethel Merman, Mel Tormé, Phil Silvers, Leslie Uggams, Paul Lynde, Vikki Carr, Mahalia Jackson, Alan King, Robert Goulet, Tony Randall and Liza Minnelli. Shelley Berman and Kay Medford turned up often as Gloria’s parents. The show also found ways to incorporate musical groups and their hits into its plot each week. On the first episode, which aired September 24, 1968, The Turtles sang “Eleanor.”

The above ticket is for August 18 and it’s for the second episode, which was telecast October 1 and told the story of how Bobby decided to ask Gloria to marry him. During the course of the hour, guest star Nancy Wilson sang “Marriage Blues,” E.J. Peaker sang, “It Must Be Him,” Morse sang, “Embarrassment of Riches,” Morse and Peaker sang “Our Love is Here to Stay” and”The Two of Us,” and Wilson and Peaker sang, “To Get a Man.” Guest stars Tim Conway and Jackie Vernon didn’t sing.

The series was a critical hit but that was about it. Audiences never discovered it…or if they did, they didn’t much like what they were watching. Twenty-six episodes were produced with the last airing April Fool’s Day of ’69. There were a few week of reruns and then the timeslot (Tuesday nights at 10) was given over to one night of a thrice-weekly Dick Cavett Show. That’s Life was never rerun again, which is a shame. It was one of those shows that deserved more of a chance.

Hudson Brothers Show, The

No sooner was The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour a hit than its producers, Allan Blye and Chris Bearde, sought to replicate that success on Saturday morn with an act called The Hudson Brothers. Promoting Bill, Brett and Mark Hudson as the seventies version of Groucho, Harpo and Chico, CBS launched them as the summer replacement for Sonny and Cher, with a show that aired in primetime from 7/31/74 to 8/28/74. This segued into the half-hour Saturday AM version, which was called The Hudson Brothers Razzle Dazzle Show. That one lasted one year, commencing 8/7/74.

Both shows featured zany sketches and music (the Brothers had some modest record hits around then) and a family of regulars that included Gary Owens and Rod Hull. Rod Hull was an Australian comedian who worked with a large bird puppet called Emu. You can read all about Rod here.

Oddly enough, the primetime version — which had only been intended to launch the brothers in preparation for their Saturday morn show — probably fared better. There was talk of later bringing it or them back in some format but the act instead drifted through other venues and the Hudsons went their separate ways.

Redd Foxx Comedy Hour, The

Here’s another ticket for a show that taped at CBS but as you can see from the absence of those letters on the ticket, the show didn’t air on CBS. It also wasn’t called The Redd Foxx Show like the ticket says. There was a later program called The Redd Foxx Show and it was a situation comedy. This one was a variety show that was broadcast on ABC as The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour.

Mr. Foxx starred in Sanford and Son from 1972 to 1977. When it was finally cancelled, he signed a big contract with ABC and this series resulted. It was produced by the team of Allan Blye and Bob Einstein, and it was a very funny, innovative series that not a lot of people watched. Foxx was joined by regulars Billy Barty, Bill Saluga and Hal Smith, along with some of his old nightclub cronies like Slappy White and “Iron Jaw” Wilson. “Iron Jaw” was a performer who was often on nightclub bills with Foxx as an opening act. His performance consisted of linking about a dozen lightweight wooden chairs into a cluster and lifting that assemblage up in his teeth. That was about all he did but Foxx kept him working. Andy Kaufman also appeared once or twice.

When Redd left NBC, there were press reports that the main point of contention had been that the network wouldn’t give him a dressing room with a window in it. The actual reason was that, given the success of Sanford and Son, he felt he deserved a lot more money than NBC was offering and also that he had more to offer than just playing Fred Sanford. He wanted, for example, to host variety specials and to guest host The Tonight Show — the latter, a demand that was vetoed by Johnny Carson. ABC offered a lot more…so off he went. The opening of his first telecast showed a shot of the ABC studio and an announcer introduced him. You then heard the voice of Redd Foxx yelling, “I ain’t comin’ out ’til I get a window!”

What followed was a funny show but America wasn’t watching. A bad time slot (Thursday nights at 10) was one reason. Another may have been that people really only loved him as Sanford. The only attention the series got was when they did a sketch spoofing Farrah Fawcett’s then-famous hair-do, It was a visit to her home where everyone — including her parents, the maid and a parrot — wore Farrah wigs. The actress sued and ABC settled with a promise that her coiffure would not be mocked on any ABC show. For a couple years there, the main taboo on an ABC show was any joke that mentioned Farrah Fawcett. Other networks could and did make fun of her but it was verboten on ABC.

Records show that The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour debuted on September 15, 1977 and last aired on January 26, 1978. The above ticket is for January 20, which makes one suspect the taping either didn’t occur or that it resulted in a show that never aired. By March of 1980, Redd Foxx was back on series television…playing Fred Sanford again.

Lennon Sisters Show, The

The Lennon Sisters were four toothy young ladies — Dianne, Peggy, Kathy and Janet — who became famous singing on The Lawrence Welk Show. How they got on that series is one of the simplest “rocket to stardom” stories in the history of show business. Lawrence Welk’s son Larry went to school with them and told his father about these sisters who were such fine vocalists. The elder Welk auditioned them and quickly added them to his “musical family,” which meant they got a lot of television exposure but not the highest paychecks.

They appeared on the Welk show from 1955 to 1968 when they decided it was time to do bigger, better-paying jobs. They’d had several successful record albums and this prompted ABC to star them in a special with special guest Jimmy Durante. (That was how Jimmy always spelled it despite the type on the above ticket.) The special did well enough to lead to a weekly series that began in September of 1969. It was called Jimmy Durante Presents The Lennon Sisters Hour.

The series began on a sad note: Six weeks before debut date, the father of the Lennon Sisters was shot to death in a parking lot. The shooter was a deranged fan who believed he was married to Peggy Lennon, and that the father was attempting to break them up. Perhaps that contributed to the low entertainment value of the series, which was cancelled in mid-season.

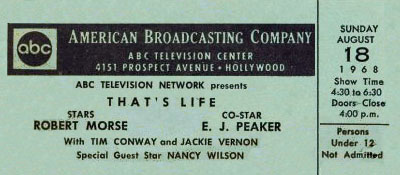

New Show, The

Lorne Michaels left his role as Executive Producer of Saturday Night Live in 1980. In 1984, NBC was in such ratings trouble in prime time that they made him one of those offers he couldn’t refuse. Reportedly, they dangled a staggering sum of cash and total freedom to do whatever he wanted with an hour on Friday nights. The problem, as many would later comment, was that Lorne Michaels didn’t have an idea for a new show, nor the time to conceive one. The New Show debuted on January 6, 1984 and was instantly labelled “Saturday Night Lite” by most critics. It was a largely unstructured hour of sketches and musical acts that was at its best when it most closely resembled the series that had made Michaels famous, offering much the same look and feel, although the show was not broadcast live. It also featured many of the same cast members and guest stars, along with several refugees from SCTV. The last episode aired on March 23. Many people have fond memories of certain sketches, especially several that featured Steve Martin, but Michaels has so far refused to release the series on DVD.