Beat the Clock (1979-1980)

This was a revival of an earlier Goodson-Todman show — one that, as I mentioned here, I never liked. I didn’t like the original with Bill Collyer. I didn’t like the 1969-1974 revival hosted by Jack Narz and later by Gene Wood. I didn’t like this version, which was hosted by Monty Hall. And though I never saw the short-lived 2002 revival hosted by Gary Kroeger, I’m pretty sure I didn’t like it, either; not if it consisted of people having to do silly stunts before a clock ran down.

Audiences didn’t warm to the 1979-1980 version either — not on TV and not even in person. You can see the desperate attempt to bolster ratings in the above tickets. The show changed from Beat the Clock to All-Star Beat the Clock, which it did by bringing celebrities in to attempt the stupid timed feats. Needless to say, “all-star” was a bit of an overstatement. You don’t get real stars to go on television and attempt to catch marshmallows in their ears while sitting on a skateboard and balancing a bowl of live guppies…in 45 seconds. The show also tried the Tattletales gimmick of having the putative celebrities play for the studio audience, thereby helping to fill the seats. Rumor has it they still had trouble filling the house. Even the homeless folks decided they’d rather go hungry.

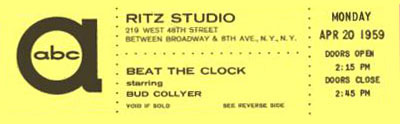

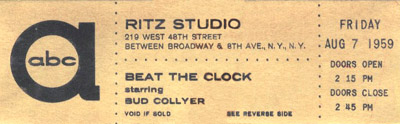

Beat the Clock (1950-1961)

Everyone has a couple of TV shows they can’t stand. Among mine are the various versions of Beat the Clock, a program built on the principle that there’s always someone who’ll humiliate themselves for a free blender. Bud Collyer was the genial host of the original version which started on radio in 1949, moved to CBS television in 1950, then shifted to ABC from 1958 to 1961. Even though Mr. Collyer had supplied the voice of Superman on radio and for animation, I was never able to warm to him as a TV host. On Beat the Clock, he got contestants to perform silly stunts while a big clock ticked off their deadlines…and there was something very condescending about the way he instructed the people in their assignments and giggled at their failures.

The Ritz Theater was an appropriate place to do Beat the Clock, as it was built on a deadline in 1921. The Shubert organization gave the contractor a mere sixty days to erect the place and his crew managed to do it. A week later, its first attraction (two short plays by John Drinkwater) went into rehearsal. It housed now-forgotten plays until 1943 when it was converted to a radio studio and later, a television facility. It closed down in 1965 and remained dark until it was purchased, renovated and reopened in 1971. In 1990, it was renamed the Walter Kerr Theater, honoring the famed Broadway critic. Over the years, dozens of theatrical productions played there, every single one of which was more entertaining than Beat the Clock.

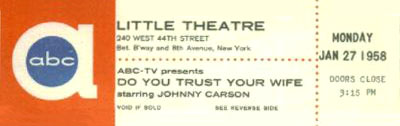

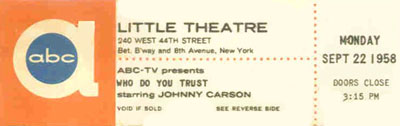

Who Do You Trust

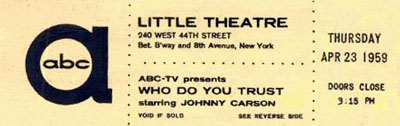

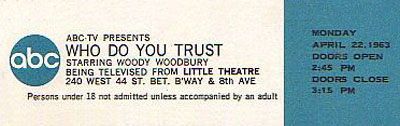

TV history books will tell you that Edgar Bergen (and wooden friends) hosted a prime-time game show called Do You Trust Your Wife? from 1956 to 1957. They will further tell you that when it shifted to daytime on July 14, 1958, its name was changed to the ungrammatical Who Do You Trust (should have been Whom and had a question mark) and that Bergen was replaced by Johnny Carson. The above tickets tell a different story. Here we see Johnny hosting the daytime version in January of ’58 and it’s still called Do You Trust Your Wife? Perhaps the name change is what occurred on the July date. On the September 22, 1958 ticket above, the name of the show is in a typeface other than the one normally used then on ABC tickets. That would suggest someone had made a quick fix on the printing plates to change the name of the program.

Writing the name of Carson’s game show without a question mark was symbolic of the program, which was a quiz show that never got around to asking many questions. Like Bergen’s version and Groucho’s You Bet Your Life, the quiz format was just an excuse for the host to banter with contestants and, in Johnny’s case, to engage in demonstrations. A belly dancer would come on to play the game and before they got to that, she’d give Johnny a lesson in her craft. It all honed and demonstrated Carson’s fine skills for making an interview interesting and participating in stunts — two of the three essential skills (the other being the monologue) that he’d display on The Tonight Show.

Occasionally, the game show got randy. Tuesday through Friday, Johnny would do the show live. On Fridays, he’d also tape a show that could air on Mondays so he and the crew could have a three-day weekend. After doing the live Friday show and before taping Monday’s, he and announcer Ed McMahon would repair to a nearby tavern for dinner and drinks, often resulting in an alcohol-enhanced taping that would be looser and dirtier than the norm and, of course, funnier. It all earned Johnny The Tonight Show, though not without a wait. When he was signed to replace Jack Paar on the late-night show, he still had six months on his Who Do You Trust contract, and that show’s producer, Don Fedderson, saw no reason to let him out early. The Tonight Show endured six months of guest hosts while Johnny hosted his afternoon program under duress, cracking jokes about ABC holding him prisoner. In actuality, it was not ABC but Fedderson, who knew that his show would not long survive the loss of Johnny…and it didn’t. Carson was finally replaced by comedian Woody Woodbury, ratings on Who Do You Trust plunged, and that was the end of that.

P.D.Q.

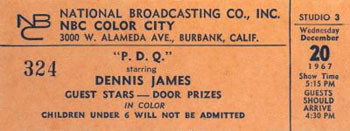

P.D.Q. was a fringe-time afternoon game show on NBC. “Fringe-time” means it was scheduled late in the afternoon and not every network affiliate carried it, so in some cities it was syndicated to non-NBC stations. The premise was that you had two teams, and at times they’d be one celebrity and one civilian. One member of each team would go into a little booth while the other member would race against the clock, running back and forth to put letters up on a board that would spell out a word or phrase. The person in the booth would have to guess the word or phrase based on seeing some but not all of the letters, and the team which “got it” in the fewest number of seconds would get the points. It was kind of like someone said, “How can we rip off Password but make it more physical?” Presiding over the game when it aired from 1965 to 1969 was Dennis James, the Iron Horse of TV game show hosting. Not long after it went off, Lin Bolen took command of NBC’s daytime game show lineup and, legend has it, she decided she didn’t want any of her programs hosted by “old men like Dennis James,” the theory being that housewives wanted someone hunkier to look at during the day. When the decision was made in 1973 to revive P.D.Q., it was retitled Baffle and Dick Enberg came in to host.

On the above ticket, one can see many indicators that P.D.Q. had trouble filling its studio audience: The long lead time between when they wanted you there and when they did the show, the door prizes, the low minimum age, etc. An awful lot of people who went to see them tape P.D.Q. probably arrived at NBC that day hoping to see something else.

Amateurs Guide To Love, The

The Amateurs Guide To Love was a messy attempt to cross-pollinate a game show with a Candid Camera type show, also folding in elements of a “let’s discuss romance” daytime program. The format changed a bit during its run but basically, a celebrity panel was shown pre-taped clips where people on the street had been caught in hidden camera stunts that were supposed to point up the way men and women acted, individually and collectively. The tape was stopped before the payoff and the panel would predict how the folks would react, with prizes going to the subjects if the panelists didn’t guess the outcome. Or something like that. I never quite understood the show; not when it was a prime-time CBS special hosted by McHale Navy‘s Joe Flynn…not when it became a daytime CBS show hosted by Gene Rayburn. The special aired in August of ’71 and the series started in March of ’72, so I’m guessing the top ticket was from a test show done at a time when the network was still deciding whether or not to pick up the daytime version. The words “special preview” are one tip-off, as is the absence of the CBS eye. They usually leave it off tickets to shows that tape at CBS facilities but air in other venues. I’m presuming they also leave it off shows that may not wind up on CBS. (A version of this show also aired briefly on the USA Network, but that was years later.)