Play Your Hunch

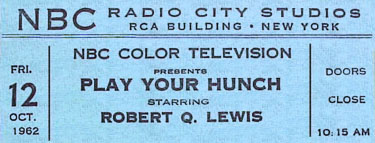

Play Your Hunch was The Game Show That Would Not Die. It started on CBS in the daytime. They cancelled it after six months. It moved to ABC, again in daytime. They cancelled it after six months. Then it moved to NBC, where it lasted four years in daytime with occasional brief forays into nighttime. I don’t know why the above tickets from 1961 and 1962 describe a program that had been on the air since 1958 as “a new audience participation show.”

Merv Griffin hosted for most of the run, and the show was pretty simple. Two teams of contestants (usually husband-wife) would be shown little puzzles, usually involving three people coming out on stage or three objects being unveiled. The correct answer to the question would be one of the three choices, which were labelled X, Y and Z. If you guessed right, you got points. That was it.

One of Merv’s big breaks came about because Play Your Hunch was done live each morning from Studio 6B in what was then called Radio City Studios. Later in the day, long after Merv and his show were out of there, the studio was reset for Jack Paar’s late night show. Mr. Paar was a nervous, superstitious gent and when he was working at NBC, he usually declined to ride the elevators at Rockefeller Center. Instead, he would reach his office each morning by an intricate series of stairwells and short-cuts. His route took him through the usually-deserted Studio 6B but one day, he arrived at the studio much earlier than usual and found himself walking onto a broadcast of Play Your Hunch.

The studio audience went berserk and Paar, finding himself unexpectedly on live TV, attempted to flee. But Merv ran over and got a vise-grip on the bewildered star’s arm to keep him there so he could conduct a brief, funny interview. Paar swore he had no idea that his studio was being used by another program each morning. “So this is what you do in the daytime,” Paar quipped to Griffin, who had occasionally sung on Tonight.

Later, Paar admitted he was impressed with how Griffin had “milked” the accident for its maximum entertainment value by keeping him there. He gave Merv a shot guest-hosting Tonight and when that went well, it led to Griffin becoming a candidate to succeed Paar and also getting signed to do The Merv Griffin Show on NBC’s daytime schedule. Merv left the game show and Gene Rayburn took over for a month. Then NBC decided to put Match Game on later in the year, Rayburn went off to get ready to host that, and Robert Q. Lewis helmed Play Your Hunch until it went off in September of 1963.

To Tell the Truth (1969-1981)

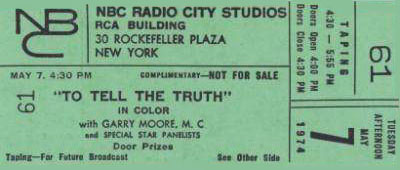

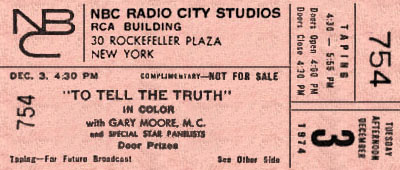

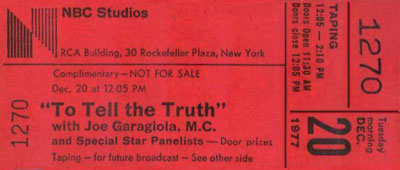

Garry Moore had a long, glorious career hosting game shows. You’d think someone would know how to spell his name on a ticket. This one was for the syndicated daytime version of To Tell the Truth, which ran from 1969 to 1981. Moore hosted until 1977 and then mysteriously disappeared. All of a sudden, Bill Cullen, and then Joe Garagiola were filling in for him “while Garry is off on a much-deserved vacation.” Audiences sensed something was wrong and began bombarding the show with mail asking what was really happening, and was the rumor true that Garry had died? No, it wasn’t — but the correspondents were right that something was wrong.

Moore had developed a cancerous node in his throat, and was off for a few months while it was removed and he got his voice back. He decided not to return to the daily or weekly grind and to retire but to deal with the rumors, he came back and hosted To Tell the Truth for one last time. His surprise walk-on at the beginning stunned the studio audience and they gave him one of the most enthusiastic, loving ovations ever on television, then later in the show fell properly silent as he explained about his operation and his retirement. Thereafter, Garagiola became the permanent host.

In deference to all the tobacco sponsors he’d had over the years — you can see him smoking incessantly on I’ve Got A Secret, brought to you by Winston cigarettes — Moore did not reveal that he’d had cancer. He died in 1993 and the cause of death was listed as emphysema.

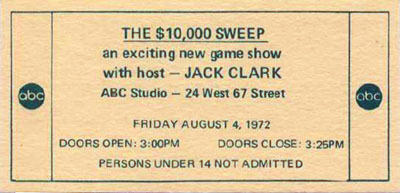

$10,000 Sweep, The

You probably haven’t heard of The $10,000 Sweep because it was an unsold game show pilot. The way it worked, two pairs of contestants competed against one another to answer questions. If a team won one game, they earned $2000. If they won two, they got $4000 and so on, for a total possible winning of a then-staggering ten grand. ABC didn’t buy the show but the notion of giving away ten thousand dollars stayed with producer Bob Stewart who soon sold The $10,000 Pyramid to CBS with Dick Clark as host. Sweep was hosted by another, unrelated Clark — Jack Clark, a frequent game show announcer and an occasional an on-camera host. He passed away in 1988 and probably still holds the record for hosting game shows that didn’t get on the air.

Not only did he preside over an amazing number of unsold pilots but he was one of the first people many producers called when they needed someone to host an untaped “run-through” of a potential program. Many shows go through dozens of such rehearsals and tests before they get anywhere near an actual pilot, and Jack Clark was the guy who — assuming he wasn’t working for pay somewhere that day — would always come over and host your run-through for little or no money. Around 1981, I worked with him on an unsuccessful effort to revive the show Rhyme and Reason in a new format. It led up to a run-through for NBC execs (and went no further) but I was impressed with Clark’s obvious experience and with how utterly cooperative he was. Charlie Brill and Mitzi McCall were the celebrity panelists and though we were doing it just once in a dingy rehearsal hall for an audience of about ten, Clark performed like he was hosting a real TV show on a real set with a full house and all of America watching. A very nice man and, as they say, a true professional.

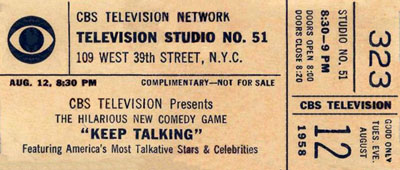

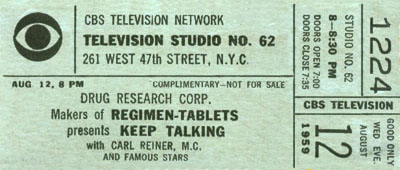

Keep Talking

Keep Talking was a prime-time game show that ran from 1958 to 1960. Each week, two teams would compete, each team composed of three celebrities. The rules changed from time to time but basically, the idea was to keep a story going with the panelists handing it off each time a bell rang, improvising wildly. Somewhere in there, they had to incorporate a secret word and the other panel had to guess the word…and as I recall from my vague memories, no one cared all that much about the scoring. The fun was in how one panelist would take the story off in some odd direction and then the next would have no idea what to do with it. Frequent players included Paul Winchell, Danny Dayton, Morey Amsterdam, Peggy Cass, Pat Carroll, Orson Bean, Audrey Meadows and Elaine May.

The show went on the air in July of 1958 and its first host was Monty Hall, a Canadian who was then fairly new to American TV. He was replaced in October because, if we believe his autobiography, the comedians on the show were complaining about him making funny remarks and competing with them. This seems unlikely, especially since his replacement was Carl Reiner, who was probably funnier than anyone on the panel. When Reiner left to do other things, Merv Griffin took over for the final season.

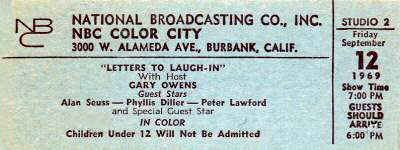

Letters to Laugh-In

Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In was a hit TV show that aired from January of 1968 to May of 1973. In September of ’69, its producers tried expanding their franchise into daytime with Letters to Laugh-In. This was back when each network’s daytime schedule was taken up with game shows and soap operas…and every year, someone would suggest, “Hey, maybe the housewives would like a change of pace.” There were several attempts to introduce comedy and/or variety into those line-ups and like Letters to Laugh-In, they didn’t last long. (The show it replaced, by the way, was the original Match Game. When Letters to Laugh-In failed to click, NBC replaced it with a soap opera, Somerset, which was a spin-off of another NBC soap opera, Another World.)

The host of Letters to Laugh-In was Gary Owens, who served as announcer of the prime-time show, and the premise was simple enough. Viewers were invited to send in their favorite jokes and each day, Gary and three guest performers would read selected jokes aloud. If your joke got read on the air, you received the tidy sum of $2.00 and there was a real prize if yours was selected as the best of the day. The worst joke won a trip to Beautiful Downtown Burbank. One of the three performers on each week of shows was a member of the prime-time cast. On the above ticket, the Laugh-In performer was Alan Sues, who apparently hadn’t been on the show long enough for the NBC ticket printers to know how to spell his name.

I recall it as a fun, fast-paced show that might have worked in another part of the day. One of the writers of the prime-time show, David Panich, was once asked about it. David said, “That was just a plot on the part of our cheap producers to establish that a joke was worth no more than two dollars.”

Money Maze, The

Nick Clooney is probably best known these days as a host on American Movie Classics and as the father of actor George Clooney. From 1974-1975, he was known as the host of The Money Maze, an ABC game show. (George worked on the staff of the program.)

It was kind of a dumb program, with couples competing for the right to challenge a huge maze that filled most of the studio. The husband would race through twists and turns in the labyrinth while his wife watched from an elevated platform called the Crow’s Nest, which gave her a view of the whole layout. She would yell out instructions — “Turn left! Turn right!” — while he tried to locate five “money towers.” These were pillars hidden in the maze which lit up when the husband pressed a button on them. One had a “1” on it; the rest had zeroes. If the hubby got all five towers lit and got out of the maze within 60 seconds, the couple won $10,000, which presumably made it all worth the effort. If he only lit the “1” tower and three zeroes, they got $1000. If he got the “1” and two zeroes, it meant $100, and I seem to recall at least one couple winning a big ten bucks. In order to win anything, the runner had to light the “1” tower and get out of the maze in the allotted time. During one phase of the show, the towers also had prize names on them; one represented a mink stole, another was a trip to Hawaii, etc.

Those of you interested in Trivial Connections might like to know that the producer of this series was the late Don Segall, whose career in TV and comic books I wrote about here. The director was Artie Forrest, who has directed as many TV shows as anyone who ever lived, most recently Whose Line Is It, Anyway? The announcer was Alan Kalter, who now works for David Letterman. And the show was under the aegis of Daphne Productions, which was Dick Cavett’s production company. Most likely, it got on the air because Cavett had received some sort of commitment from ABC as part of the contract for his late night talk show.

The show had a short run, in part because ABC was then having clearance problems with its late afternoon programming (it only ran in about half the country) but to a great extent because the set was so involved. Segall told me that it took a huge crew at least 24, sometimes 48 hours to set up the maze, which was rearranged for every tape day. At the time, there were only a few studios in New York that could accommodate it and they were in such demand that they charged a fortune in rental. Every time the producers of Money Maze went in to tape a new block of shows, they had to pay for several days of studio rental to set up, and then it cost an absurd amount in overtime to strike the set and store it away. Don described it as the first game show where the stage crew took home more money than the contestants.

It was a pretty clear ancestor of the so-called “reality shows” of today but don’t expect to see it on the Game Show Network. Word is that all but one or two of the tapes of Money Maze were erased, due either to neglect or the Clooneys paying someone off.

Concentration (1958-1973)

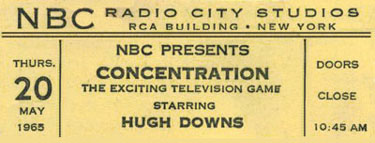

Hugh Downs was the announcer/sidekick on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show when NBC asked him to also host a daytime game show. It made for a long workday but Downs agreed and Concentration went on the air. It was a very simple game of memory, strategy and perception, and you won if you could uncover the pieces of a hidden rebus and solve it.

There was also a prime time version of Concentration in 1958 and 1961. At first, it was jazzed up with more lights and music, and Downs was ignominiously passed over for the moderator position, which went to Jack Barry who, with his partner Dan Enright, owned and produced the show. When ratings proved disappointing, NBC decided it needed Downs after all, and he agreed on the condition that they remove the “improvements.” This was done, he took over the nighttime version…and its ratings went up.

Downs was very proud and protective of the series. At a time when it was revealed that certain other game shows were rigged and their handlers — Jack Barry and Dan Enright — were being shamed out of the business, Downs happily pointed out that Concentration was practically rig-proof. Even if someone had given a contestant the answer, they couldn’t do much with it. If they solved the puzzle too early, they didn’t win much in the way of prizes. If they waited until the bounty grew to a hefty size, they risked losing control of the game board, which meant that their opponent would win. And at no point could the winnings equal the kind of megabucks that characterized the shows that were fixed. Nevertheless, Downs himself was known to skulk around and investigate to make sure the game he was fronting was as honest as he represented it to be. That honesty was one of the things that kept Concentration on the air for so long. When the game show scandals hit, NBC quietly bought out the interests of Barry and Enright, removed all mention of them from the show’s history, and kept things running.

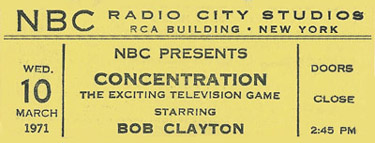

After Paar left The Tonight Show, Downs took over The Today Show…but he retained the Concentration job until 1969 when the workload got to be too much for him. When he announced his desire to quit the game show, the network asked him to stay on for an extra four months past the expiration of his contract to help them with an important ratings period. Downs agreed on the condition that the show’s announcer, Bob Clayton, be given the host’s job after him. Downs and Clayton were friends, and Clayton had filled in for Downs a few times and done the show the way Downs felt it should be done. As someone who had himself been typecast for a time as an off-camera announcer, Downs felt that Clayton was deserving of the on-camera gig, so he made the condition. NBC agreed and Clayton got the assignment…but not for long. Another Tonight Show sidekick, Ed McMahon, had been hosting Snap Judgment, another game show for NBC. When it was cancelled, Clayton was booted from Concentration and McMahon installed in his place. Downs was furious at the double-cross. Several months later, realizing McMahon wasn’t working out, an NBC executive actually phoned Downs and asked, “Do you know how we can reach Bob Clayton?” Downs later said he tried not to be too smug.

Clayton returned as emcee until the show was cancelled in 1973. Jack Narz hosted a syndicated revival that ran from 1973 to 1979 and then Alex Trebek hosted Classic Concentration, which ran from 1987 to 1991.

That @&$# Quiz Show

John and Greg Rice were twin dwarves who were featured on several segments of Real People. Their odd but funny style caught the imagination of Real People host John Barbour, who was then sitting up his own production company and who had some limited experience with bad parody TV games. When The Gong Show started, Barbour was the host for the first week of programs taped for daytime. Producer Chuck Barris hated Barbour’s approach, junked the five shows and took over the position himself.

A few years later, operating on a shoestring budget, Barbour assembled That @&$# Quiz Show with the Rice Twins as hosts who posed very bizarre questions to very baffled contestants. Little is remembered of the show, which lasted in syndication only a few weeks in 1982. Some stations dropped it after one week. My recollection of one viewing is that the program wasn’t quite a quiz show and it wasn’t quite a spoof of a quiz show, falling uncomfortably between the two, and that the Rices tried hard but had no clue as to what they were supposed to do. The most interesting thing about the series was probably that its scenery and key art were designed by Mad Magazine cartoonist Sergio Aragonés, who had also been featured on Real People. That’s his lettering and drawing on the ticket above.

The show’s title was usually pronounced on-air with the punctuation marks replaced by a cacaphony of sound effects. When people who worked on the show gave its title, they often referred to it as That Awful Quiz Show. Most people took the easy route and never mentioned it at all.

Tattletales

Tattletales evolved out of an earlier Goodson-Todman game show called He Said, She Said. In this new version, three celebrity couples competed to see who knew the most about his or her mate. The audience was divided in thirds and each celebrity couple was playing for one segment of the audience, which would divide up the celebs’ winnings. The show paid off then and there: As audience members left, they were handed a check from an automatic check-writing machine. Each “rooting section” had 122 people in it, and the winning celebrity couple’s section might split around $1200 while the losing couples might each have earned $300-$400 for their section. So if you went and sat through the taping of a few episodes, you might take home twenty bucks — not a huge amount, but twenty bucks more than any other show paid you to sit there and applaud. There were homeless folks in the area who went to Tattletales tapings and made enough money to eat for a few days and there were merchants located around CBS who put up signs that said, “We cash Tattletales checks.”

Bert Convy was the host of this series that ran from February of 1974 to March of ’78, then returned to the air in January of ’82 and ran ’til June of 1984 — not a bad run and there was a syndicated version, as well. A few years ago, when Game Show Network acquired the series, they did promos that emphasized the rather amazing percentage of celebrity couples who’d appeared together on Tattletales and divorced soon after.

Family Feud (1988-1995)

Ray Combs was a nervous little man who turned up in the Los Angeles stand-up comedy circuit in the early-to-mid eighties with an absolutely terrible act — the kind of thing a non-professional might whip up for the Rotary Club’s annual pancake breakfast. But he seemed like a nice guy and he sure tried hard. And if his act wasn’t good enough to get him work as a real stand-up, it did land him some gigs doing audience warm-ups — a job that often serves as a kind of consolation prize for those denied real careers in comedy. Combs wasn’t too funny but he was so likeable and eager to succeed that studio audiences took to the guy, and he started developing some “buzz.” Jim McCawley, who was then booking comedians for Johnny Carson took an enormous gamble and put him on in 1986.

The act was still unsophisticated, and more than a few veteran stand-ups remarked that of all the performers they couldn’t imagine would ever make The Tonight Show, Combs was near the top of the list. Amazingly, he not only got on but he did well. (I saw him that evening and it seemed like the audience didn’t find him funny but thought he was trying so hard he deserved a huge ovation.) The spot got him a lot of attention and some high-profile auditions.

Two years later, Mark Goodson wanted to revive the game show Family Feud for syndication but needed a new host — preferably someone who’d be a lot more cooperative and inexpensive than the original emcee, Richard Dawson. They almost went with Joe Namath but when negotiations got difficult, Combs got the job. The above tickets would have been to some of his first shows, and things went well enough for a few years. But shortly after Mark Goodson passed away, ratings took a nosedive. In an unsuccessful effort to save the program, Jonathan Goodson (who’d taken over his father’s company) fired Combs and brought back Dawson, who didn’t fare any better. From that point on, the life and times of Ray Combs took a downward spiral — bad investments, other shows that didn’t make it, a bad car accident that left him with chronic back problems. Deeply depressed, he was finally placed in an institution where in 1996, he took his own life. He only had a few years of his dream but as others have pointed out, that’s a lot more than some people get.