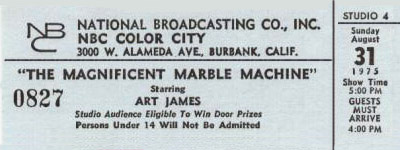

Magnificent Marble Machine, The

Pinball was big in 1975 but someone at the NBC and the game show company Heatter-Quigley didn’t seem to grasp that people liked to play it, not to watch it. In fact, it’s frustrating watching someone else do something like that because you keep thinking when you’d push the button and every time they miss, you want to elbow them aside and take over.

People also liked the new, high-tech pinball machines that were coming out and had very little interest in a huge, clunky lower-tech one called The Magnificent Marble Machine. Also, of course, the folks who were flocking to arcades to play pinball were not the housewives who had to tune in if a game show was going to be successful. So right there, you had more than enough reasons for this one to be a fast flop. Which it was.

It went on NBC in July of that year with Art James as the host and by December, the big pinball machine was in storage. Mr. James was a very good, fast-on-his-feet master of ceremonies who had hosted two modest successes in the game show field — Say When and The Who, What or Where Game. But between and after them, he had the misfortune to get hired for a string of less-than-classics. They included Blank Check, Catch Phrase, Fractured Phrases, Pick and Choose, The Shopping Game, Temptation and Pay Cards. After several in a row failed quickly, he stopped getting called for emcee jobs and returned to his previous station as a game show announcer. Not long before he retired, he had a role in Kevin Smith’s movie, Mallrats, playing — you guessed it — a game show host.

The Magnificent Marble Machine involved two teams (each with one celebrity and one civilian) competing in a question round and then the winning team got to play the big pinball machine. The question round was a bore: Clues were displayed on a screen and players had to buzz in and identify what they were describing. But the pinball machine wasn’t much more exciting. It was twenty feet high and twelve feet wide and the two players on the team had to work the flippers, keep a large ball in play and try to light up bumpers. The more bumpers that were lit up, the bigger the contestant’s winnings. But the flippers didn’t flip so well and it often felt like someone was losing out on the big money because Adrienne Barbeau couldn’t make work the controls properly.

I visited the set one time when my friends, Charlie Brill and Mitzi McCall, were the celebs. They struggled in a pre-taping practice session to learn how to make the flippers flip…but by taping time, they’d both failed to light up one bumper. “I hope nobody’s planning on winning anything today,” Charlie quipped. When they started playing for real, it almost went that way. I remember standing next to the machine during a break and having a great urge to play it, which the crew wouldn’t let me do because then they’d have to let everyone on the set play with it. Everyone wanted to…but like all of America, we had no interest in watching somebody else play it.

By the way: I like that line on the tickets that says, “Studio audience eligible to win door prizes.” Note that it doesn’t actually say that there are door prizes or that someone who attends a taping will win one. It just says that if you’re there, you’re eligible for any door prizes that might occur. The folks who played that day with Charlie and Mitzi were eligible to win things too and didn’t.

Danny Thomas Show, The

The Danny Thomas Show started out on ABC in 1953 as Make Room for Daddy. The show revolved around the home life of nightclub entertainer Danny Williams, and the original title was derived from a situation in Thomas’s own home life. For several years, the only way he could make a living was “on the road,” and he was away from his Los Angeles home and family for weeks, sometimes months at a time. Whenever he was about to return for a while, his family would scurry about their house to clear closet and drawer space for him, and they’d say, “Make room for Daddy.”

ABC originally contracted for a sitcom with a different premise but the assigned writer, Mel Shavelson, was having trouble making it work. One day in a meeting, Danny pleaded with him to find a way because he was counting on a hit series to enable him to stay home with his family. He told Shavelson some anecdotes about the problems he was having and the writer said, in effect, “That’s a much better idea for a show.” So art imitated life and the storyline was switched. The resultant series achieved modest ratings, and some of those involved believed the network only kept it on because a top ABC exec had a crush on actress Jean Hagen, who played Danny’s wife.

In 1956, however, Ms. Hagen decided she wanted out and in what may have been a television “first,” it was announced that her character had died. The show became the story of widower Danny dating new women, trying to find a second wife for himself and a mother for his kids. ABC decided America didn’t care; that without Jean Hagen, there was no show so they cancelled it. Thomas would later attribute what happened next to his prayers to St. Jude, but it was more likely the work of his much-more-powerful agent, Abe Lastfogel. CBS picked up what was now called The Danny Thomas Show and the 1957 season opener was about him returning from his honeymoon with one of the women he’d dated, a nurse played by Marjorie Lord. (Reruns of earlier shows were being syndicated under the Make Room for Daddy title. Some people would never stop calling it that.)

On CBS and in a better time slot, the show flourished and rode high atop the ratings until it ended in 1965. By that time, it had made Thomas (and his partner, Sheldon Leonard, who’d appeared on the show and directed many episodes) moguls in television production. Bill Dana, Joey Bishop and Andy Griffith had all appeared on The Danny Thomas Show in roles calculated to lead to spin-offs, and spin off they did: The Bill Dana Show, The Joey Bishop Show and The Andy Griffith Show. The latter spin-off even spun-off a spin-off with Gomer Pyle, USMC. The Thomas-Leonard company produced others, as well, including The Dick Van Dyke Show, which filmed on the adjoining stage.

The best thing about The Danny Thomas Show was probably the supporting cast, especially Sid Melton as the nervous owner of a local nightclub where Danny Williams played, and Pat Carroll as his wife. The greatest joy came in the occasional appearances of Hans Conried as Danny’s flamboyant Uncle Tonoose. He would make grand entrances, bursting in the front door with suitcases that suggested a long visit as he proclaimed loudly, “Tonoose is here!” Thomas himself was a good, likeable straight man for the crazies around him and his comic timing carried a lot of contrived story premises. The show pretty much lasted until TV outgrew a taste for warm family comedies where the father is a bit of a jackass but does the right thing in the last scene.

In 1970, ABC revived the show they should never have let get away in the first place with Make Room for Granddaddy but its era had long passed. One season and out.

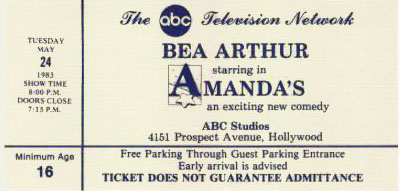

Amanda’s

Bea Arthur starred in Maude from 1972 to 1978. In February of 1983, she returned to series television in Amanda’s (also known as Amanda’s by the Sea), a show which continued the tradition of adapting hit British programs for American TV. Apart from the hotel setting though, it was difficult to tell that Ms. Arthur’s comeback show was an Americanization of Fawlty Towers, which starred its co-creator, John Cleese, as the less-than-stable hotel proprietor Basil Fawlty.

Cleese accepted no responsibility for the U.S. version and refused to allow his name to be used in the credits. He was satisfied to just cash the checks and puzzle as to just what the American producers thought they’d purchased. In one interview, he described a phone call from one of them explaining, “We’ve made a tiny change…we’ve written Basil out of the show.” In actuality, what they’d done was to take Mr. Fawlty and give him a sex change. Bea Arthur’s character, Amanda Cartwright, was also nicer than Fawlty and less given to the kind of rudeness and hysterics that had made the original show so funny. Still, it was nice to see Ms. Arthur again. Two years later, she would be back with more success as one of The Golden Girls.

It was the second of three unsuccessful attempts to turn Fawlty Towers into a U.S. sitcom. The first, Snavely, starred Harvey Korman as hotel entrepreneur Henry Snavely, who was not unlike a nicer Basil, with Betty White as his spouse. It was an unsold 1978 pilot. Five years later, we had Amanda’s, which lasted six episodes. And then in 1999, there was yet another short-lived attempt with John Laroquette in the title role of Payne, a sitcom also known as Royal Payne. All vanished quickly but the reruns of Fawlty Towers continue, as popular as ever. What can we learn from this?

Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell

The idea was to replicate the format of The Ed Sullivan Show, only to do it on Saturday nights with Howard Cosell. And right there you had at least two fatal errors. Saturday night isn’t the night that the family gathers around the TV after supper, the way they did for years to watch Ed. And Howard Cosell was many things — including, people forget, a man who brought a new honesty and maturity to sportscasting — but he wasn’t Ed Sullivan. Cosell wasn’t warm and friendly, and he lacked Ed’s credibility as an endorser of talented people.

And there may have been a third fatal error (maybe the Sullivan show had left the airways because the format had gotten stale and antiquated) and perhaps even a fourth (exec producer Roone Arledge was proficient in sports and news, not entertainment). The end result was a show that only had two things in common with Ed’s old show: It was done in the same studio and it was cancelled.

Ed had been cancelled after 23 years. “Humble Howard,” as some called him, was axed after four months. (Most histories say three.) The top ticket above is to the dress rehearsal of the first episode which aired September 20, 1975 and which tried to capture some of the excitement Ed had achieved by booking The Beatles. What the Cosell show had was an audience packed with screaming teenage girls and, on stage, The Bay City Rollers. Not quite the same thing. The other ticket above is for the next-to-last broadcast, the last being on January 17, 1976.

The whole effort is probably best remembered by its connection to another show that debuted less than a month later. Over at NBC, producer Lorne Michaels had wanted to call his new late night show Saturday Night Live but the name was taken so he settled for NBC Saturday Night. After the Cosell program went off, Michaels’ show took custody of the name as of its 3/26/77 broadcast.

Also, the Cosell series had a small regular comedy troupe of three performers — Bill Murray, Brian-Doyle Murray and Christopher Guest — who were billed as “The Prime Time Players.” It inspired the name of the comedy squadron on Michaels’ show, The Not-Ready-For-Primetime Players. And of course, all three men — Guest and the two Murray brothers — wound up in the cast of the NBC late night series at different times.

My most vivid memory of Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell is that one evening, Howard waded out into the audience to do a brief interview with two men who’d been invited to be there. They were Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman, who were then waging a public campaign to pressure DC Comics to come across with pensions and other financial assistance. The spot gave their cause a nice bit of publicity and it probably helped a little to shame DC into doing the right thing. So Howard, as dislikeable as he could be at times, did something nice. And it would have been even nicer if he hadn’t kept referring to Joe Shuster as “John.”

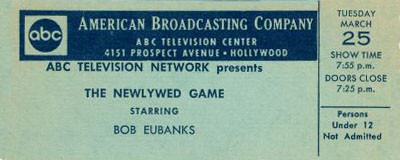

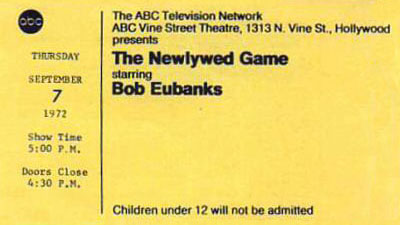

Newlywed Game, The

A friend of mine told me that once when he and his wife needed new furniture, they rehearsed a little routine in which they embarrassed each other by revealing “secrets” which they made up for the occasion. Like, they decided to blurt out that the husband liked to dress in the wife’s clothing, and that her cooking gave him diarrhea at least once a week. Then they went and auditioned for The Newlywed Game, quarrelling the entire time and letting such things “slip.” They were instantly booked as contestants.

Once in front of the cameras, they dropped the act and behaved like dignified human beings, despite the fact that the questions they were asked seemed calculated to evoke the humiliating stories from the audition. They left with their self-esteem relatively intact, plus a new bedroom set. They also received a tongue-lashing from the show’s Contestant Coordinator who realized they’d been “had,” and warned them that they would never get on another Chuck Barris game show as long as they lived. So far, it hasn’t bothered them too much. (The top ticket, by the way, seems to be from 1969.)

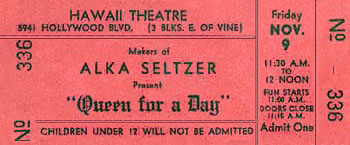

Queen for a Day

Queen For A Day was an offensive, voyeuristic show that capitalized on the misery of its contestants, and I’m surprised no one has tried reviving it lately. Basically, a number of women were paraded on camera each episode to tell why they should be named “Queen For A Day” and awarded a big prize package. Ostensibly, that honor was to go to someone who’d done something to deserve it, but the show usually devolved into the ladies telling about how awful their lives were; how their husbands had left them or died and how their mother was ill and how the roof on their home was collapsing, etc. Somehow, went the premise, some of this would be put right and their lives set on a happier course if the show’s studio audience would vote them “Queen For A Day” which meant they’d get crowned with a tiara and sent home with a box of small appliances. There were a lot of tears, and I guess America’s homemakers liked to watch and cry along, and think, “Thank God that woman has it worse than me,” or something of the sort. An awful spectacle, especially when you considered all the women who cried and poured their hearts out on network TV and didn’t even win the Waring Blender and the case of Noxzema that the winner got.

The show moved around to various studios in Hollywood, broadcasting for a time from (as above) the Hawaii Theatre , which was another of Sid Grauman’s “international” film palaces. The Chinese and The Egyptian were, and still are, further west on Hollywood. The Hawaiian is now a Salvation Army church. I’m guessing the above ticket is from 1953, when the show was seen only on television in Los Angeles. It went network in 1956 on NBC, moved to ABC in 1960 and finally went off in 1964.

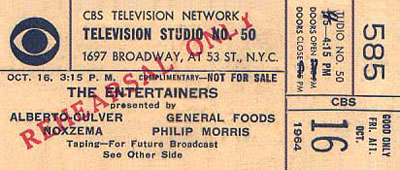

Entertainers, The

The Entertainers probably sounded like a good idea –a variety show starring not one but three stars: Bob Newhart, Carol Burnett and Caterina Valente. Each week, one, two or all three of them would perform songs and sketches, working with a crew of rotating special guest stars that included Ruth Buzzi, John Davidson, Dom DeLuise, Don Crichton, and newspaper columnist Art Buchwald. At times, it was difficult to tell the stars from the guest stars, and the lack of focus seemed to keep audiences at bay. Eventually, Newhart departed and a concerted attempt was made to feature Burnett and Valente as co-hosts — but they had little chemistry and by then, it was too late. The show was cancelled after seven months and the only one who profited from the experience was Carol Burnett. CBS signed her to a long-term contract for specials and guest appearances, and this eventually led to The Carol Burnett Show. Newhart, of course, came back later to great success — but among the many biographies and specials that have recounted the careers of Burnett and Newhart, there is almost no mention of The Entertainers. (This ticket was donated to this site by Brian Gari, for which we thank him kindly.)

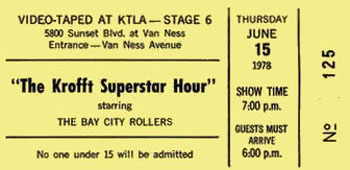

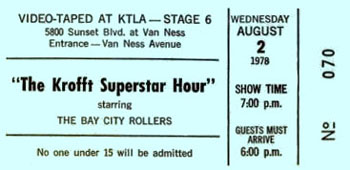

Krofft Superstar Hour

I was actually one of the writers for this one, which was produced for NBC’s 1978 Saturday morning line-up by Sid and Marty Krofft. That season, the whole schedule was pretty much a disaster so after a few weeks, they switched some shows around, dumped others and the Krofft Superstar Hour was chopped down to a half-hour called The Bay City Rollers Show. In its shortened form, it stayed on the NBC Saturday morning schedule for a couple years of the same thirteen episodes being rerun over and over and over again. (I don’t think half of the last two hours we produced ever even aired.)

The show featured The Bay City Rollers and an all-star roster of characters from past Krofft shows: H.R. Pufnstuf, Witchiepoo, Seymour the Spider, Stupid Bat, Hoodoo (the villain from Lidsville, played on our show not by Charles Nelson Reilly but by a gent named Paul Gale, who did a darn good impression of him) and others. Jay Robinson, who’d portrayed Dr. Shrinker on the series of the same name, and Billy Barty, who played his assistant, played identical characters under different names. Also in the cast were Louise DuArt, Sharon Baird, Mickey McMeel, Patty Maloney, Van Snowden and voice actors Lennie Weinrib and Walker Edmiston. This show should not be confused with The Krofft Super-Show, which was on ABC a season or two earlier, but quite a few books on TV history don’t seem to know the difference.

When I signed on to work on the show, it was to have been hosted by ABBA — or so said a powerful agent who swore he represented that group and would deliver them. ABBA was at a low point it its/their career and reportedly eager/willing to do a kids’ show for American TV…but negotiations broke down and we instead got The Bay City Rollers, who were on a similar downturn. Our show was, in fact, the “last hurrah” of the group as composed primarily of the original Rollers. Their Scottish accents and awkwardness delivering intros and comedy material had a certain charm, even if it rendered much of what we wrote unintelligible. Still, I got along great with the guys even though they weren’t getting along so well with one another. At the time, one of them was suing the others, so a certain tension hung over the set.

We had an interesting technical problem on the show, in part because the membership of the Rollers had changed from time to time. Almost all the musical performances consisted of the Rollers lip-syncing to records they’d made a few years earlier…and in one or two cases, guys who were currently in the group were performing to recordings that hadn’t involved them, and they were mouthing the words to someone else’s voices. That made their lip-sync work less convincing than it otherwise might have been. Even when a musician performs to his own track, it is not uncommon for them to be a fraction of a second behind the audio so when you can, you go in and slip the picture a few frames later to compensate. Our editors found that they couldn’t do this easily with the Rollers. All five of the guys were moving their lips a quarter of a second late but the drummer, Derek, was right on the beat. Director Jack Regas, who’d done hundreds of hours of musical numbers for TV, said he’d never seen anything quite like it. Even Derek was a tiny bit behind with his singing but his sticks hit the drum in absolute precision…so if we’d moved the vocal tracks to put the lip movements in sync, the visual of him drumming would have been off. The post-production people had to go in and slide the picture only on angles where you couldn’t see Derek…and on shots of him playing and singing, they had to decide which of the two to let be out of sync. They usually opted to keep the drums in time.

The moment tickets like the above were made available, they were immediately gobbled up by a squadron of teenage girls who staked out the studio every day, and occasionally found their way to a house up in Laurel Canyon where one faction of the Rollers was staying. The writers took turns doing the audience warm-ups for the tapings — the easiest job ever in show business. You just had to walk out and say the name of one of the Rollers and the girls in the bleachers, many of whom were clearly under the minimum age listed on the tickets, would scream themselves into a frenzy. (By the way: Industry legend, which is so often wrong, said that Stage 6 at KTLA was where Al Jolson filmed The Jazz Singer in 1929. Longtime TV producer Joel Tator notes that Stage 6 wasn’t even built at the time, and theorizes that Mr. Jolson actually performed on what is now Stage 9. Either way, when I worked there, everyone told us it was “Where Jolson made The Jazz Singer” and one got the feeling the place hadn’t been cleaned much since then.)

Our Miss Brooks (TV)

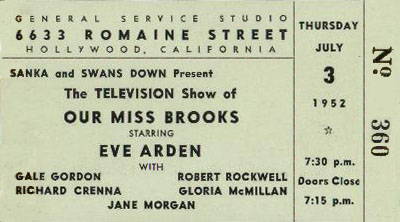

In 1951, I Love Lucy went on TV, not only becoming a smash hit but inventing the way most situation comedies would be filmed thereafter — in front of a live audience with multiple cameras. The show was produced by Desilu, a company owned by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, and they were quickly asked if their studio and methods could be employed for other shows. The first new one they took on was the TV adaptation of the radio show, Our Miss Brooks,. which was filmed on the same stage used for I Love Lucy on other days. The TV version of Our Miss Brooks went on the air October 3, 1952 so the above ticket is probably for one of the very first filmings, maybe even the first.

It was a period when many popular radio shows were being transferred to television but Our Miss Brooks was different from most. For one thing, it employed pretty much the same cast. Most programs recast because the radio actors didn’t always look the way they sounded…but Eve Arden, Gale Gordon, Richard Rockwell, Richard Crenna and all the rest were suitable for their roles. (Buying Crenna as a teenager was a bit of a stretch — he was 26 at the time — but they got away with it.) Also unusual was that the same producers and cast continued to do the show for radio every week for many years.

The TV show was a modest hit for its first three years. Audience enjoyed watching high school English teacher Connie Brooks (Arden) battle with the school’s principal, Osgood Conklin (Gordon) while she lusted after the handsome Biology teacher, Mr. Boynton (Rockwell). But when ratings dipped in 1955, the show underwent a revamp. Miss Brooks and Mr. Conklin moved from Madison High to a private elementary school where they were surrounded by a new supporting cast. The change failed to boost tune-in and that was the last season. The show went off in 1956, the same year a feature film of Our Miss Brooks was released. It was set back in the high school and ended with Miss Brooks and Mr. Boynton finally getting married, thereby ending the series, once and for all.

Our Miss Brooks (Radio)

For years, Eve Arden made a pretty good living playing sarcastic, wise-cracking second leads in movies. She even got an Oscar nomination in 1945 for her role in Mildred Pierce. But around that time, she decided it was time to broaden her appeal and try to get some lead roles and parts that were less abrasive. She managed both with the hit radio show Our Miss Brooks, which went on the air in 1948. It cast her as Connie Brooks, an English teacher at Madison High School who struggled with wayward students and red-tape bureaucracy. Connie was a bit nicer than most of the characters she’d played before, which is to say she only skewered people now and then.

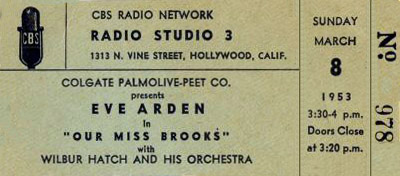

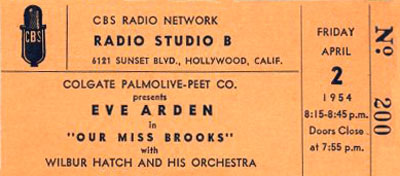

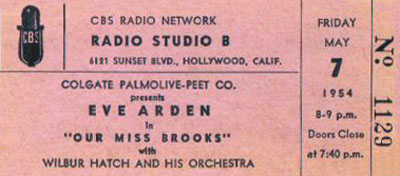

Sharing the mike with her were veteran comic actor Gale Gordon (as the school principal, Osgood Conklin), Robert Rockwell (as Biology teacher Philip Boynton), Richard Crenna (as gawky student Walter Denton) and a wide array of good character actors as pupils and faculty. Wilbur Hatch, whose name is familiar to everyone from the I Love Lucy credits, conducted the orchestra.

Our Miss Brooks aired on Sunday nights. The first ticket above from 3/8/53 is for a live broadcast done from the CBS studio on Vine Street. The other two tickets are from 1954, by which time the show was being recorded Friday evenings at the CBS facility on Sunset for transmission the following Sunday evening. It lasted on the air until 1956, by which time it had already made a successful transition to television with pretty much the same cast.