Mary Tyler Moore Show, The

If you’d attended a filming of Ms. Moore’s classic sitcom — and sadly, I never did — you would probably have heard a warm-up performed by writer Lorenzo Music, who later gained fame as the voice of Carlton the Doorman (on Rhoda) and Garfield the Cat. For a time, shows produced by the MTM company dominated CBS Studio Center in the valley — a facility built on land that had once housed Mack Sennett’s second studio. Sennett erected it just as his business was dying out due to changing audience tastes, as well as the coming of sound film. The property was sold in a bankruptcy hearing and went through several owners before becoming Republic Studios, birthplace of many a movie serial and “B” western. It had moved into renting out space to others by 1963 when CBS leased the place, eventually buying it outright.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show was the sitcom that changed seventies’ television. As is well known, the network was not fond of the script and format devised by writers James Brooks and Allan Burns, and the advance testing of the show predicted a sure-fire flop. Less well known is how the show came to be at all. After The Dick Van Dyke Show, Mary Tyler Moore had attempted to establish a motion picture career. Thoroughly Modern Millie was a modest success but then What’s So Bad About Feeling Good? and Don’t Just Stand There suggested that ticket buyers were not racing to see Laura Petrie on the big screen. A disastrous attempt at a Broadway musical (Breakfast at Tiffany’s) also helped convince her that her place was on television. And what really convinced her (and CBS) was a 1969 special in which she reteamed with her former co-star. Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman was an hour of songs and sketches that earned rave reviews and strong ratings.

It got Mary the offer she needed to return to the world of situation comedy and soon, she not only had a hit show but a production company that produced many of them, including spin-offs Rhoda and Phyllis, as well as acclaimed, unrelated sitcoms including The Bob Newhart Show, WKRP in Cincinnatti, The Tony Randall Show and many more. After The Mary Tyler Moore Show left the air in 1977, she again tried movies and Broadway with mixed success but again fled back to television. She starred in Mary (1978), The Mary Tyler Moore Hour (1979) and another show called Mary (1985).

That @&$# Quiz Show

John and Greg Rice were twin dwarves who were featured on several segments of Real People. Their odd but funny style caught the imagination of Real People host John Barbour, who was then sitting up his own production company and who had some limited experience with bad parody TV games. When The Gong Show started, Barbour was the host for the first week of programs taped for daytime. Producer Chuck Barris hated Barbour’s approach, junked the five shows and took over the position himself.

A few years later, operating on a shoestring budget, Barbour assembled That @&$# Quiz Show with the Rice Twins as hosts who posed very bizarre questions to very baffled contestants. Little is remembered of the show, which lasted in syndication only a few weeks in 1982. Some stations dropped it after one week. My recollection of one viewing is that the program wasn’t quite a quiz show and it wasn’t quite a spoof of a quiz show, falling uncomfortably between the two, and that the Rices tried hard but had no clue as to what they were supposed to do. The most interesting thing about the series was probably that its scenery and key art were designed by Mad Magazine cartoonist Sergio Aragonés, who had also been featured on Real People. That’s his lettering and drawing on the ticket above.

The show’s title was usually pronounced on-air with the punctuation marks replaced by a cacaphony of sound effects. When people who worked on the show gave its title, they often referred to it as That Awful Quiz Show. Most people took the easy route and never mentioned it at all.

Don Rickles Show, The

There was a time when network executives were sure that Don Rickles could be the star of a big hit TV series if only someone could find the right vehicle. In a very short time, Mr. Rickles went through more vehicles than Jay Leno has in his garage. There were pilot scripts that were filmed, pilot scripts that were not filmed, specials and even a couple of shows that made it onto the air. One attempt in 1972 basically tried to turn him into Dick Van Dyke but with a slight twist. Rickles, someone said to someone else, would articulate the anger that we all feel in day-to-day problems. So one episode was about him trying to get his TV repaired and running into bureaucracy and insane people. Another was about him trying to get his car repaired and running into bureaucracy and insane people…and so on. Otherwise, it was pretty much The Dick Van Dyke Show but without the magic.

The Rickles sitcom took place in a living room set that looked like it had been furnished by the same people who designed Rob and Laura Petrie’s home. Don Robinson had a lovely wife (Louise Sorel) who kinda reminded you of Laura, a daughter (Erin Moran) who was a lot like Ritchie, and a best friend (Robert Hogan) who had all the traits of Jerry Helper. Instead of writing The Alan Brady Show, he worked in an ad agency and instead of New Rochelle, he lived in Long Island, New York. Sheldon Leonard, who had executive produced The Dick Van Dyke Show, executive produced The Don Rickles Show. Mr. Leonard also did the audience warm-up, at least at the filming I attended, and I wrote about it in this article. In it, I also note that when Leonard wrote his autobiography years later, he discussed every TV show with which he was involved except that The Don Rickles Show went curiously unmentioned.

The series was quickly forgotten after its thirteen weeks were up. And judging from the lack of promotion it received and the fact that CBS moved it around between several less-than-promising time slots, it would seem everyone had given up on this one long before the final episode aired. Rickles wouldn’t find a decent format for television until four years later and C.P.O. Sharkey…and even that only lasted two years.

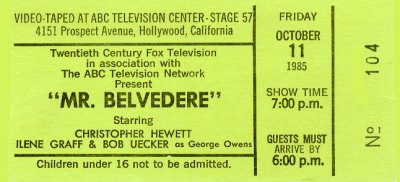

Mr. Belvedere

I always thought Mr. Belvedere was a stealth TV show. It was on for six seasons with respectable ratings but all during that time, I never heard one person mention it, either on TV or in my presence. Bob Uecker would go on the Carson show and casually mention his main line of work before lapsing into very funny tales of his days in baseball. (Uecker claimed to have been a lousy player who never got any respect. He didn’t get a lot in his TV career, either. On the second of the above tickets, his name is misspelled.) I don’t recall seeing any of its other stars anywhere. In fact, the only time I can recall any of my friends mentioning it was an actor pal who was up for a sitcom and who said he hoped it would be like Mr. Belvedere — a show that stays on a long time and earns its cast tons of money, and the network keeps not canceling it because even they forget it’s on. ABC Television Center at Prospect and Talmadge is in the Los Feliz area, where a lot of movie studios were built back in the silent days. This one was originally Vitagraph Pictures, but it went through many hands and remodels before becoming ABC’s main production facility in L.A. In 2000, it became a secondary site to a new studio built in Glendale, but some soap operas still tape there.

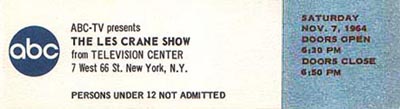

Les Crane Show, The

A radio host named Les Crane figured into ABC’s early attempts to get into the late night market. Crane’s show went for serious talk about issues in a cross between what Mike Wallace had done and what Phil Donahue would do, with much participation from a studio audience. They were seated in a kind of amphitheater formation around the stage, and if someone in the house had a question to ask or a point to make, they’d stand up and Crane would aim his “shotgun mike” at them — a microphone that actually looked like a shotgun — supposedly to pick up their voices. (Some critics suggested the device was more for theatrics than audio.)

It was a pretty good show, though sometimes a bit overly-dramatic. ABC gave up on Crane after four months, renamed the show Nightlife and tried an array of guest hosts, none of whom clicked. So they brought Crane back, added Nipsey Russell as co-host, and tried to do a more entertainment-oriented show, which did even less well. Eventually, Crane went back to radio, and The Joey Bishop Show got the time slot. The above ticket was for one of Crane’s very first shows and it displays one of the reasons his initial format didn’t work. This was a Monday-Friday show discussing what was going on in the world, right? So why were they taping it on Saturday evening? (Thanks to Brian Gari for the ticket.)

Tattletales

Tattletales evolved out of an earlier Goodson-Todman game show called He Said, She Said. In this new version, three celebrity couples competed to see who knew the most about his or her mate. The audience was divided in thirds and each celebrity couple was playing for one segment of the audience, which would divide up the celebs’ winnings. The show paid off then and there: As audience members left, they were handed a check from an automatic check-writing machine. Each “rooting section” had 122 people in it, and the winning celebrity couple’s section might split around $1200 while the losing couples might each have earned $300-$400 for their section. So if you went and sat through the taping of a few episodes, you might take home twenty bucks — not a huge amount, but twenty bucks more than any other show paid you to sit there and applaud. There were homeless folks in the area who went to Tattletales tapings and made enough money to eat for a few days and there were merchants located around CBS who put up signs that said, “We cash Tattletales checks.”

Bert Convy was the host of this series that ran from February of 1974 to March of ’78, then returned to the air in January of ’82 and ran ’til June of 1984 — not a bad run and there was a syndicated version, as well. A few years ago, when Game Show Network acquired the series, they did promos that emphasized the rather amazing percentage of celebrity couples who’d appeared together on Tattletales and divorced soon after.

New Dick Van Dyke Show, The

The original Dick Van Dyke Show left the CBS airwaves in 1966 and its two main stars — Mary Tyler Moore and Mr. Van Dyke — plunged into movies, both with disappointing results. In 1969, they co-starred in a variety special, Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman, that led to offers to return full-time to television. Dick said no and returned to his new home in Arizona. Mary said yes and The Mary Tyler Moore Show went on the air and became a large hit. This prompted CBS to up its offer to Van Dyke…but Dick was happy in Arizona and not interested in returning to L.A. to do a new series. The solution was to remodel and upgrade a studio near Van Dyke’s new desert home and to do the show there…the first network prime-time TV show ever filmed in Carefree, Arizona and (one suspects) the last.

It was titled The New Dick Van Dyke Show though they sometimes omitted the “new,” as you might note in the tickets above. There’s no “new” on the second season ticket but there is on the third season ticket. The first two years were produced in Arizona with Carl Reiner running things, and found Dick playing Dick Preston, a talk show host at a mythical Phoenix TV station, KXIU. Hope Lange played his spouse and suffered the unenviable fate of having most of America say, “They don’t have the same chemistry he had with Mary.” Well, at least the guys at CBS said that, and as her role was downplayed and more of the action centered around the talk show, rumors circulated that Ms. Lange wanted out.

She stayed but one attempt to build an installment more around her relationship with Dick drove Carl Reiner away. Near the end of the second season, CBS rejected an episode in which the Prestons’ young daughter accidentally walked into the bedroom of Mommy and Daddy while Mommy and Daddy were having sex. This happened off-camera and Reiner insisted the scene was tastefully done, very funny and that it had been properly vetted by consultants whose opinions should be honored. CBS refused, the episode never aired and Reiner quit. The series itself was almost cancelled then but Van Dyke had a firm three-year contract and CBS had a hole in its schedule that seemed to need the show.

For what turned out to be its final season, the no-longer-new New Dick Van Dyke Show moved to Hollywood where a new creative team did a remodelling job. Apart from Ms. Lange and Angela Powell (the actress who played their daughter), the entire supporting cast was let go. Dick Preston became an actor on a daytime soap opera, and new cast members were added. They included Richard Dawson (who played a TV cooking host not unlike Graham “The Galloping Gourmet” Kerr), Chita Rivera, Barry Gordon, Henry Darrow, Barbara Rush and Dick Van Patten. Ratings went up but Van Dyke’s interest in the whole project went down and at the end of the season and after completing 72 episodes, he announced he was done with it and with series television. And he never did another series again except for Van Dyke and Company (1976), The Van Dyke Show (1988) and Diagnosis Murder (1993-2001).

Family Feud (1988-1995)

Ray Combs was a nervous little man who turned up in the Los Angeles stand-up comedy circuit in the early-to-mid eighties with an absolutely terrible act — the kind of thing a non-professional might whip up for the Rotary Club’s annual pancake breakfast. But he seemed like a nice guy and he sure tried hard. And if his act wasn’t good enough to get him work as a real stand-up, it did land him some gigs doing audience warm-ups — a job that often serves as a kind of consolation prize for those denied real careers in comedy. Combs wasn’t too funny but he was so likeable and eager to succeed that studio audiences took to the guy, and he started developing some “buzz.” Jim McCawley, who was then booking comedians for Johnny Carson took an enormous gamble and put him on in 1986.

The act was still unsophisticated, and more than a few veteran stand-ups remarked that of all the performers they couldn’t imagine would ever make The Tonight Show, Combs was near the top of the list. Amazingly, he not only got on but he did well. (I saw him that evening and it seemed like the audience didn’t find him funny but thought he was trying so hard he deserved a huge ovation.) The spot got him a lot of attention and some high-profile auditions.

Two years later, Mark Goodson wanted to revive the game show Family Feud for syndication but needed a new host — preferably someone who’d be a lot more cooperative and inexpensive than the original emcee, Richard Dawson. They almost went with Joe Namath but when negotiations got difficult, Combs got the job. The above tickets would have been to some of his first shows, and things went well enough for a few years. But shortly after Mark Goodson passed away, ratings took a nosedive. In an unsuccessful effort to save the program, Jonathan Goodson (who’d taken over his father’s company) fired Combs and brought back Dawson, who didn’t fare any better. From that point on, the life and times of Ray Combs took a downward spiral — bad investments, other shows that didn’t make it, a bad car accident that left him with chronic back problems. Deeply depressed, he was finally placed in an institution where in 1996, he took his own life. He only had a few years of his dream but as others have pointed out, that’s a lot more than some people get.

Beat the Clock (1979-1980)

This was a revival of an earlier Goodson-Todman show — one that, as I mentioned here, I never liked. I didn’t like the original with Bill Collyer. I didn’t like the 1969-1974 revival hosted by Jack Narz and later by Gene Wood. I didn’t like this version, which was hosted by Monty Hall. And though I never saw the short-lived 2002 revival hosted by Gary Kroeger, I’m pretty sure I didn’t like it, either; not if it consisted of people having to do silly stunts before a clock ran down.

Audiences didn’t warm to the 1979-1980 version either — not on TV and not even in person. You can see the desperate attempt to bolster ratings in the above tickets. The show changed from Beat the Clock to All-Star Beat the Clock, which it did by bringing celebrities in to attempt the stupid timed feats. Needless to say, “all-star” was a bit of an overstatement. You don’t get real stars to go on television and attempt to catch marshmallows in their ears while sitting on a skateboard and balancing a bowl of live guppies…in 45 seconds. The show also tried the Tattletales gimmick of having the putative celebrities play for the studio audience, thereby helping to fill the seats. Rumor has it they still had trouble filling the house. Even the homeless folks decided they’d rather go hungry.

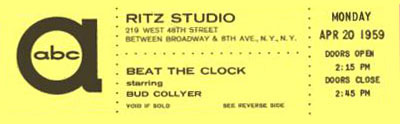

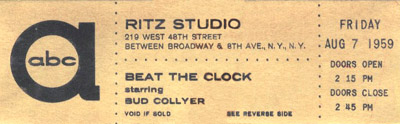

Beat the Clock (1950-1961)

Everyone has a couple of TV shows they can’t stand. Among mine are the various versions of Beat the Clock, a program built on the principle that there’s always someone who’ll humiliate themselves for a free blender. Bud Collyer was the genial host of the original version which started on radio in 1949, moved to CBS television in 1950, then shifted to ABC from 1958 to 1961. Even though Mr. Collyer had supplied the voice of Superman on radio and for animation, I was never able to warm to him as a TV host. On Beat the Clock, he got contestants to perform silly stunts while a big clock ticked off their deadlines…and there was something very condescending about the way he instructed the people in their assignments and giggled at their failures.

The Ritz Theater was an appropriate place to do Beat the Clock, as it was built on a deadline in 1921. The Shubert organization gave the contractor a mere sixty days to erect the place and his crew managed to do it. A week later, its first attraction (two short plays by John Drinkwater) went into rehearsal. It housed now-forgotten plays until 1943 when it was converted to a radio studio and later, a television facility. It closed down in 1965 and remained dark until it was purchased, renovated and reopened in 1971. In 1990, it was renamed the Walter Kerr Theater, honoring the famed Broadway critic. Over the years, dozens of theatrical productions played there, every single one of which was more entertaining than Beat the Clock.