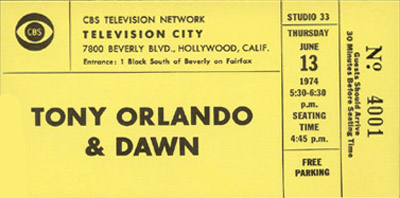

Tony Orlando & Dawn

Before he “made it,” Tony Orlando drifted back and forth between working behind the scenes in the record business and in front of the microphone. Once he and two back-up singers scored big with “Candida,” “Knock Three Times” and “Tie a Yellow Ribbon ‘Round the Ole Oak Tree,” TV execs came calling, hoping the replicate the success of Sonny and Cher in a variety format. Orlando and the two ladies who comprised Dawn (Telma Hopkins and Joyce Vincent Wilson) didn’t quite have the same knack for snappy and mutually-insulting banter but their show had enough music and enough energy, as well as a stellar array of guests. It debuted as a summer series in 1974 and managed to stick around until December of ’76. For its last gasp, it was renamed The Tony Orlando and Dawn Rainbow Hour, as a way of signalling that it was undergoing some kind of unspecified revamp. The new title doesn’t seem to have meant much difference to anyone.

The reference on one of the above tickets to the audience being seen on camera refers to a weekly segment in which Orlando would wade out into the crowd, perform in the aisles and sometimes get audience members up to sing and dance with him. It became a signature routine of his and one that sparked battles amidst the show’s production staff and at the network, some of whom felt it was amateurish. The live audience loved it (no surprise) and each week, the producers would way overtape such material, then quarrel in the editing room over how much to include. There’d be pointed arguments that every song that Tony performed with a fat lady in an aisle seat meant they’d have to cut out a polished, rehearsed musical spot with one of the show’s well-paid and professional guest stars. On the other hand, even those who fought for less audience numbers had to admit that Tony was never better than when he and his fans were energizing one another. He had a genuine love for the people who came to see his shows tape (and vice-versa) and that probably is what is best remembered from that series.

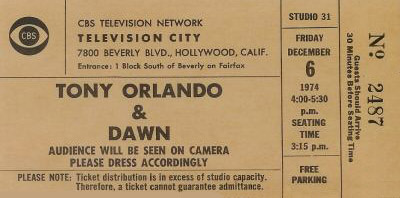

Jerry Lewis Show, The (1967-1969)

Jerry Lewis has had a checkered career on television. He and Dean Martin scored big on The Colgate Comedy Hour (1950-1955) where they were among the show’s rotating hosts. A series of specials did well but then in 1963, he attempted a two-hour live variety/talk show for ABC that was one of television’s most spectacular disasters. It was supposed to be a two-year “firm” committment but after dismal ratings and killer reviews, Lewis announced he was too busy with his film career to do television and exited after thirteen weeks.

Four years later, that film career was starting to fade and he reappeared on NBC with a more conventional variety series done, unlike his earlier efforts which were all live, on tape. It debuted on September 19, 1967 to indifferent response and disappointing ratings. (Lewis was said to have been unamused by the unidentified person who, the day before his debut, papered the NBC studios and Lewis’s car with signs that said, “Ban the bomb before it goes off.”) But NBC believed that Jerry might catch on, as his former partner had with The Dean Martin Show, and kept the fesitivities going for two years. The final broadcast was May 27, 1969.

It was not a great show. Jerry seemed to have trouble relating to any guest or topic that couldn’t have been on the old Colgate Comedy Hour. Many of the guests and jokes actually did date back that far. The sketches were weak and much of the show was devoted to Jerry’s questionable singing talents. Some people seem to recall that during this period, he and Dean exchanged cameo guest appearances but that never happened. Dean did, however, take time on his show to ask people to watch Jerry’s first episode.

Jerry Lewis never had another TV series after that…unless you count his annual Labor Day telethon to benefit Muscular Dystrophy. In 1984, he starred in a week of pilot episodes for a talk show. Thought he trotted out heavyweight guest stars — including Frank Sinatra on the opener — the show didn’t click. Reviewers faulted it (rightly) for devoting way too much of its air time to the host, the guests and sidekick Charlie Callas all discussing the greatness of each other. Since then, Jer has been a frequent guest star on other shows, slowly ascending to Legend status. My favorite of all his appearances was one night when he was on with David Letterman and Dave asked him, as a personal favor, just to run around the stage and act crazy. Jerry was a bit puzzled but he obliged.

Walter Winchell Show, The

By 1956, when The Walter Winchell Show went on the air, its star was no longer the all-powerful newspaper columnist he had once been. There had been a time when a mention in Winchell’s syndicated gossip/news column would make a career and a pan would destroy it. But newspapers were losing their clout and TV networks were establishing real news divisions. Winchell’s excited delivery had sounded gripping on his radio broadcasts but when he transferred his act to television, he looked silly — an old man reading copy and yelling, pounding randomly on a telegraph key.

Another newspaper columnist, Ed Sullivan, was a success with a variety show on CBS. Sullivan and Winchell loathed each other from past feuds, and some said Winchell was consumed with envy that his old rival was a hit where he was not. The Walter Winchell Show was supposed to rectify that but it was a flop from its first broadcast on October 5, 1956. Unlike Sullivan, who introduced the top acts and then got out of the way, Winchell fancied himself a hoofer and insisted on performing. He also found himself unable to get big stars to appear, as he’d promised the network he could. Ten years earlier, he could have snapped his fingers and had anyone in show business. By ’56, not only did few stars see any reason to curry favor with Winchell (and perhaps alienate Sullivan) but many were still mad at him for things he’d printed about them in the past.

The above ticket is probably from the show’s last New York telecast. In desperation, it was moved to Hollywood in the hope that he could round up stars on that coast. John Wayne showed up, telling reporters who asked, “Walter’s been nice to me for years. It’s about time I kissed his ass.” But Wayne was about the only biggie who appeared and the series was cancelled after thirteen weeks — a humiliating failure. The following year, Walter tried again with The Walter Winchell Files, a cop show anthology based allegedly on cases Winchell had covered in his newspaper days. Another one season disappointment. For all his fame in newspapers and on radio, Walter Winchell was only involved in one success on television. From 1959 to 1963, he was the narrator of the TV series, The Untouchables.

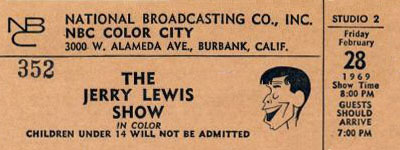

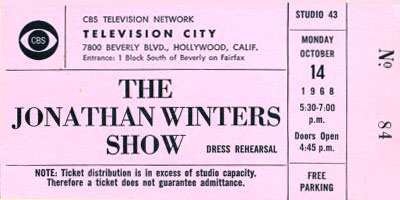

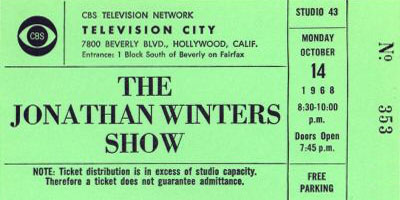

Jonathan Winters Show, The (1967-1969)

I doubt there’s a comedian anywhere who doesn’t hail Jonathan Winters as one of the greats, and whenever I’ve been around the man, I’ve seen an unending stream of people stop to tell him he’s the funniest man alive. With such unanimity of opinion, it’s amazing that Winters hasn’t had more steady work on television. What he does, he does better than anyone…but producers have sometimes been unable to package it in a format that fit neatly into a TV schedule.

The first Jonathan Winters Show was a fifteen-minute program that ran from 1956 to 1957 on NBC, following the evening newscast which then was fifteen minutes in length. It lasted about nine months.

In the mid-sixties, Winters starred in a string of network specials that got high ratings and good reviews, and appeared as a semi-regular on The Andy Williams Show. It all led to CBS, in 1967, installing him in the second Jonathan Winters Show. Most of the show consisted of sketches in which Winters played characters from his repertoire, especially the irrepressible Maude Frickert. Comedian Dick Curtis appeared in most sketches, usually as straight man, and one of the show’s producers, John Aylesworth, functioned as announcer and occasional performer. In addition to them, a number of stars turned up often enough to be considered semi-regulars: Abby Dalton, Paul Lynde, Alice Ghostley, Minnie Pearl and Cliff “Charley Weaver” Arquette.

The highlight of most episodes was the opening, which pretty much consisted of Jonathan standing on stage, letting the audience suggest characters and scenes for him to improvise. Folks at the network suggested that the staff devise some good premises and have them planted among the legitimate suggestions, but Jonathan insisted that not be done. A friend of mine who worked on the show said it wasn’t done and it wasn’t necessary…though of course, they did tape much more than was needed and edit it down for air.

The two above tickets are for the dress rehearsal and taping for the episode produced on October 14, 1968, midway through its second and final season. Later, Winters starred in several other shows, specials and unsuccessful pilots but there never seemed to be a permanent home on TV for the funniest man alive. Our loss.

Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell

The idea was to replicate the format of The Ed Sullivan Show, only to do it on Saturday nights with Howard Cosell. And right there you had at least two fatal errors. Saturday night isn’t the night that the family gathers around the TV after supper, the way they did for years to watch Ed. And Howard Cosell was many things — including, people forget, a man who brought a new honesty and maturity to sportscasting — but he wasn’t Ed Sullivan. Cosell wasn’t warm and friendly, and he lacked Ed’s credibility as an endorser of talented people.

And there may have been a third fatal error (maybe the Sullivan show had left the airways because the format had gotten stale and antiquated) and perhaps even a fourth (exec producer Roone Arledge was proficient in sports and news, not entertainment). The end result was a show that only had two things in common with Ed’s old show: It was done in the same studio and it was cancelled.

Ed had been cancelled after 23 years. “Humble Howard,” as some called him, was axed after four months. (Most histories say three.) The top ticket above is to the dress rehearsal of the first episode which aired September 20, 1975 and which tried to capture some of the excitement Ed had achieved by booking The Beatles. What the Cosell show had was an audience packed with screaming teenage girls and, on stage, The Bay City Rollers. Not quite the same thing. The other ticket above is for the next-to-last broadcast, the last being on January 17, 1976.

The whole effort is probably best remembered by its connection to another show that debuted less than a month later. Over at NBC, producer Lorne Michaels had wanted to call his new late night show Saturday Night Live but the name was taken so he settled for NBC Saturday Night. After the Cosell program went off, Michaels’ show took custody of the name as of its 3/26/77 broadcast.

Also, the Cosell series had a small regular comedy troupe of three performers — Bill Murray, Brian-Doyle Murray and Christopher Guest — who were billed as “The Prime Time Players.” It inspired the name of the comedy squadron on Michaels’ show, The Not-Ready-For-Primetime Players. And of course, all three men — Guest and the two Murray brothers — wound up in the cast of the NBC late night series at different times.

My most vivid memory of Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell is that one evening, Howard waded out into the audience to do a brief interview with two men who’d been invited to be there. They were Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman, who were then waging a public campaign to pressure DC Comics to come across with pensions and other financial assistance. The spot gave their cause a nice bit of publicity and it probably helped a little to shame DC into doing the right thing. So Howard, as dislikeable as he could be at times, did something nice. And it would have been even nicer if he hadn’t kept referring to Joe Shuster as “John.”

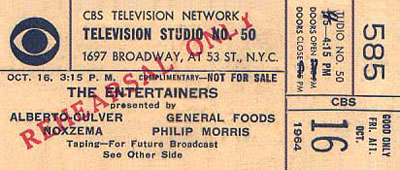

Entertainers, The

The Entertainers probably sounded like a good idea –a variety show starring not one but three stars: Bob Newhart, Carol Burnett and Caterina Valente. Each week, one, two or all three of them would perform songs and sketches, working with a crew of rotating special guest stars that included Ruth Buzzi, John Davidson, Dom DeLuise, Don Crichton, and newspaper columnist Art Buchwald. At times, it was difficult to tell the stars from the guest stars, and the lack of focus seemed to keep audiences at bay. Eventually, Newhart departed and a concerted attempt was made to feature Burnett and Valente as co-hosts — but they had little chemistry and by then, it was too late. The show was cancelled after seven months and the only one who profited from the experience was Carol Burnett. CBS signed her to a long-term contract for specials and guest appearances, and this eventually led to The Carol Burnett Show. Newhart, of course, came back later to great success — but among the many biographies and specials that have recounted the careers of Burnett and Newhart, there is almost no mention of The Entertainers. (This ticket was donated to this site by Brian Gari, for which we thank him kindly.)

Hollywood Palace, The

In 1963, ABC cleared two hours of Saturday night and refurbished a theater on Vine Street in Hollywood for a live Jerry Lewis talk show that was a spectacular and costly flop. Originally announced as a firm two-year deal, Jerry’s attempt was cancelled after 13 episodes, leaving the network with two problems: What to do with that two hours on Saturday night and what to do with that theater they’d purchased and rebuilt. They solved the second problem and half of the first by creating The Hollywood Palace, a one-hour variety show featuring the kind of vaudeville acts that had once placed the famed Palace Theater in New York. Though taped, the show strived for a “live” feel and acts were often recorded in one long, continuous take with little editing.

The host changed each week with Bing Crosby filling the post on the first show (January 4, 1964), the last (February 7, 1970) and twenty-eight other times in-between. Other frequent hosts were Milton Berle, Sid Caesar, Sammy Davis Jr. and Jimmy Durante. Durante was so popular on the show that after he hosted one that guest-starred The Lennon Sisters (December 5, 1967), ABC tried spinning-off a separate show, Jimmy Durante Presents the Lennon Sisters, which also taped at the Hollywood Palace. It didn’t last long. More successful was what happened after the one time Dean Martin hosted, which was the episode broadcast June 13, 1964. Both ABC and NBC offered him a weekly show, NBC won out and The Dean Martin Show went on the air in September of the following year.

Perhaps the most memorable episodes were the two hosted by Groucho Marx — 3/14/64 and 4/10/65. The latter featured the final performance of Margaret Dumont, re-creating a scene from the Marx Brothers film, Animal Crackers.

The top ticket above — for a taping on 2/22/64 — lists “Efram Zimbalist” as host. Actually, his name was Efrem Zimbalist Jr. and the following September, he became the star of an ABC series, The F.B.I. His Hollywood Palace episode, which aired a week after taping, featured comic actor Louis Quinn (who’d appeared with Zimbalist on 77 Sunset Strip), Kate Smith, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans with The Sons of the Pioneers, comedian Corbett Monica, comedy team Lewis and Christy, Alex Rix and his Trained Russian Bears, Adagio dancers Szony and Claire, and the famed high-wire act, The Great Wallendas.

The second ticket above, for an episode that aired May 22, 1965, featured host Tennessee Ernie Ford and his guests, Edie Adams, Ann Miller, comedian Jack Carter, acrobat Santos, The Gus Augspurg Monkeys and the O’Keffe comedy divers.

The third ticket is for an episode broadcast December 10, 1966. Host Jimmy Durante welcomed The Turtles, comedian George Carlin, actor Peter Lawford, singer Elaine Dunn, The Polack Brothers’ Elephants and two very famous acts. One was the great pantomime clown George Carl, not to be confused with Mr. Carlin. George Carl toured the globe with an act that no less than Johnny Carson once described as the funniest twenty minutes in the history of show business. It basically consisted of Carl attempting to perform a harmonica routine and getting himself hopelessly tangled in the microphone cord — one of those “you had to see it” routines. Also on the bill that evening at the Palace was Mrs. Miller, who had a brief, inexplicable career singing pop songs of the day, hopelessly out of style and key.

The fourth ticket is for the sixth season opener which aired 9/28/68 and featured host Bing Crosby, comedian Sid Caesar, folk singer Bob Gibson, jazz singer Abbey Lincoln and country-western singer Jeannie C. Riley and pop singer Bobby Goldsboro.

And the last ticket is for one that aired October 25, 1969 with host Englebert Humperdinck, comedian Jack E. Leonard, singer Nancy Ames, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Sid Caesar in a sketch with Maureen Arthur and Mickey Deems, and singer Lonnie Donegan.

One other performer deserves mention. At the end of each episode, that week’s host would read the list of who’d be performing on the stage the following week. The list was brought to him by the show’s “Billboard Girl,” an attractive model chosen for her poise and showgirl figure. For a while, it was a then-new actress named Raquel Welch. She went on to better things.

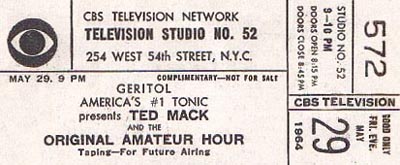

Original Amateur Hour, The

It always struck me as a little odd that everyone on Ted Mack’s show had talent except Ted Mack. I also don’t recall ever seeing anyone on that show whose talents, real though they may have been, seemed likely to lift them to any other spot in the great pantheon of show business. A few of the folks who appeared on The Original Amateur Hour later had careers but not because of that show. I mean, Robert Klein appeared on Mr. Mack’s show as part of a doo-wop group called The Teen-Tones, but that didn’t lead to a single job. Moreover, the success rate, given how long the show was on the air and how many talented amateurs it showcased, was amazingly low. How did it stay on the air, between radio and TV, for almost 40 years? I’d guess that the early part of the run had appeal because America was still climbing out of The Great Depression, and there was a certain thrill to listening to some poor kid get a chance to play his ocarina on radio and maybe, just maybe, get discovered and strike it rich.

But I can tell you what kept the show on the air its last decade or so, and the magic word is right there on the above ticket: Geritol. Its makers had discovered that certain kinds of shows were very good for selling their product. Today, one hears a lot about demographics and advertisers who seek a young audience. Geritol did the opposite: They wanted to reach people who might purchase “America’s #1 tonic,” which meant mostly older folks. To that end, they sponsored a number of shows — Lawrence Welk’s being the prime example — even when the overall ratings weren’t grand. Today, a network might refuse the business (as ABC eventually cancelled Welk, despite Geritol’s wishes) on the grounds that a couple of older-skewing shows can drag down the rest of the schedule. But back then, individual sponsors had more clout, especially over certain time slots. So Ted Mack stayed on, despite a lack of talent or, at times, much of an audience.

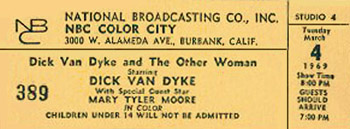

Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman

In 1969, with their film careers not going quite the way they wanted, Dick Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore reunited for an hour of songs and sketches themed around the various aspects of dating and marriage. Critics raved about Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman and audiences loved it. It led to offers for both Dick and Mary to return to series television and soon after, Mary was working on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. And a year after that made a hit, Dick Van Dyke was doing The New Dick Van Dyke Show.

Mary Tyler Moore Hour, The

A few years after The Mary Tyler Moore Show ended its historic run, Mary decided she not only wanted to be back on television but to venture into the then-dying field of variety programming, Her first attempt (titled simply Mary) was a quick failure, yanked from the airwaves before it could do irreparable damage to her stardom. A year later, she was back with a new format that tried to split the difference between variety and a situation comedy. On The Mary Tyler Moore Hour, she played TV star Mary McKinnon, who was engaged in the business of starring in a weekly variety series. Most weeks, the storyline involved securing a couple of guests to appear on her program and within the framework of that scenario, there was ample opportunity to sing, dance and do sketches. But it all felt forced and contrived, and no one was too happy with the result.

A writer who worked on the show once told me that among the reasons that its makers gave for the failure was that Mary felt out of place. Even though they surrounded her with friends (like Nancy Walker), she still would have been happier if they could have done the show at the facility at Radford. Unfortunately, that studio was still primarily film and did not seem to have an available stage suitable for a big variety show. The venue was probably not a major reason for the show not working but it seems to have been at least a tiny contributing factor. (Bob Newhart stuck to the same building when he attempted to follow his hit MTM sitcom.)