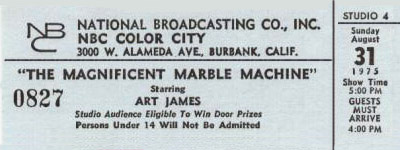

Magnificent Marble Machine, The

Pinball was big in 1975 but someone at the NBC and the game show company Heatter-Quigley didn’t seem to grasp that people liked to play it, not to watch it. In fact, it’s frustrating watching someone else do something like that because you keep thinking when you’d push the button and every time they miss, you want to elbow them aside and take over.

People also liked the new, high-tech pinball machines that were coming out and had very little interest in a huge, clunky lower-tech one called The Magnificent Marble Machine. Also, of course, the folks who were flocking to arcades to play pinball were not the housewives who had to tune in if a game show was going to be successful. So right there, you had more than enough reasons for this one to be a fast flop. Which it was.

It went on NBC in July of that year with Art James as the host and by December, the big pinball machine was in storage. Mr. James was a very good, fast-on-his-feet master of ceremonies who had hosted two modest successes in the game show field — Say When and The Who, What or Where Game. But between and after them, he had the misfortune to get hired for a string of less-than-classics. They included Blank Check, Catch Phrase, Fractured Phrases, Pick and Choose, The Shopping Game, Temptation and Pay Cards. After several in a row failed quickly, he stopped getting called for emcee jobs and returned to his previous station as a game show announcer. Not long before he retired, he had a role in Kevin Smith’s movie, Mallrats, playing — you guessed it — a game show host.

The Magnificent Marble Machine involved two teams (each with one celebrity and one civilian) competing in a question round and then the winning team got to play the big pinball machine. The question round was a bore: Clues were displayed on a screen and players had to buzz in and identify what they were describing. But the pinball machine wasn’t much more exciting. It was twenty feet high and twelve feet wide and the two players on the team had to work the flippers, keep a large ball in play and try to light up bumpers. The more bumpers that were lit up, the bigger the contestant’s winnings. But the flippers didn’t flip so well and it often felt like someone was losing out on the big money because Adrienne Barbeau couldn’t make work the controls properly.

I visited the set one time when my friends, Charlie Brill and Mitzi McCall, were the celebs. They struggled in a pre-taping practice session to learn how to make the flippers flip…but by taping time, they’d both failed to light up one bumper. “I hope nobody’s planning on winning anything today,” Charlie quipped. When they started playing for real, it almost went that way. I remember standing next to the machine during a break and having a great urge to play it, which the crew wouldn’t let me do because then they’d have to let everyone on the set play with it. Everyone wanted to…but like all of America, we had no interest in watching somebody else play it.

By the way: I like that line on the tickets that says, “Studio audience eligible to win door prizes.” Note that it doesn’t actually say that there are door prizes or that someone who attends a taping will win one. It just says that if you’re there, you’re eligible for any door prizes that might occur. The folks who played that day with Charlie and Mitzi were eligible to win things too and didn’t.

Danny Thomas Show, The

The Danny Thomas Show started out on ABC in 1953 as Make Room for Daddy. The show revolved around the home life of nightclub entertainer Danny Williams, and the original title was derived from a situation in Thomas’s own home life. For several years, the only way he could make a living was “on the road,” and he was away from his Los Angeles home and family for weeks, sometimes months at a time. Whenever he was about to return for a while, his family would scurry about their house to clear closet and drawer space for him, and they’d say, “Make room for Daddy.”

ABC originally contracted for a sitcom with a different premise but the assigned writer, Mel Shavelson, was having trouble making it work. One day in a meeting, Danny pleaded with him to find a way because he was counting on a hit series to enable him to stay home with his family. He told Shavelson some anecdotes about the problems he was having and the writer said, in effect, “That’s a much better idea for a show.” So art imitated life and the storyline was switched. The resultant series achieved modest ratings, and some of those involved believed the network only kept it on because a top ABC exec had a crush on actress Jean Hagen, who played Danny’s wife.

In 1956, however, Ms. Hagen decided she wanted out and in what may have been a television “first,” it was announced that her character had died. The show became the story of widower Danny dating new women, trying to find a second wife for himself and a mother for his kids. ABC decided America didn’t care; that without Jean Hagen, there was no show so they cancelled it. Thomas would later attribute what happened next to his prayers to St. Jude, but it was more likely the work of his much-more-powerful agent, Abe Lastfogel. CBS picked up what was now called The Danny Thomas Show and the 1957 season opener was about him returning from his honeymoon with one of the women he’d dated, a nurse played by Marjorie Lord. (Reruns of earlier shows were being syndicated under the Make Room for Daddy title. Some people would never stop calling it that.)

On CBS and in a better time slot, the show flourished and rode high atop the ratings until it ended in 1965. By that time, it had made Thomas (and his partner, Sheldon Leonard, who’d appeared on the show and directed many episodes) moguls in television production. Bill Dana, Joey Bishop and Andy Griffith had all appeared on The Danny Thomas Show in roles calculated to lead to spin-offs, and spin off they did: The Bill Dana Show, The Joey Bishop Show and The Andy Griffith Show. The latter spin-off even spun-off a spin-off with Gomer Pyle, USMC. The Thomas-Leonard company produced others, as well, including The Dick Van Dyke Show, which filmed on the adjoining stage.

The best thing about The Danny Thomas Show was probably the supporting cast, especially Sid Melton as the nervous owner of a local nightclub where Danny Williams played, and Pat Carroll as his wife. The greatest joy came in the occasional appearances of Hans Conried as Danny’s flamboyant Uncle Tonoose. He would make grand entrances, bursting in the front door with suitcases that suggested a long visit as he proclaimed loudly, “Tonoose is here!” Thomas himself was a good, likeable straight man for the crazies around him and his comic timing carried a lot of contrived story premises. The show pretty much lasted until TV outgrew a taste for warm family comedies where the father is a bit of a jackass but does the right thing in the last scene.

In 1970, ABC revived the show they should never have let get away in the first place with Make Room for Granddaddy but its era had long passed. One season and out.

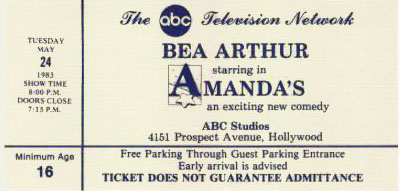

Amanda’s

Bea Arthur starred in Maude from 1972 to 1978. In February of 1983, she returned to series television in Amanda’s (also known as Amanda’s by the Sea), a show which continued the tradition of adapting hit British programs for American TV. Apart from the hotel setting though, it was difficult to tell that Ms. Arthur’s comeback show was an Americanization of Fawlty Towers, which starred its co-creator, John Cleese, as the less-than-stable hotel proprietor Basil Fawlty.

Cleese accepted no responsibility for the U.S. version and refused to allow his name to be used in the credits. He was satisfied to just cash the checks and puzzle as to just what the American producers thought they’d purchased. In one interview, he described a phone call from one of them explaining, “We’ve made a tiny change…we’ve written Basil out of the show.” In actuality, what they’d done was to take Mr. Fawlty and give him a sex change. Bea Arthur’s character, Amanda Cartwright, was also nicer than Fawlty and less given to the kind of rudeness and hysterics that had made the original show so funny. Still, it was nice to see Ms. Arthur again. Two years later, she would be back with more success as one of The Golden Girls.

It was the second of three unsuccessful attempts to turn Fawlty Towers into a U.S. sitcom. The first, Snavely, starred Harvey Korman as hotel entrepreneur Henry Snavely, who was not unlike a nicer Basil, with Betty White as his spouse. It was an unsold 1978 pilot. Five years later, we had Amanda’s, which lasted six episodes. And then in 1999, there was yet another short-lived attempt with John Laroquette in the title role of Payne, a sitcom also known as Royal Payne. All vanished quickly but the reruns of Fawlty Towers continue, as popular as ever. What can we learn from this?

Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell

The idea was to replicate the format of The Ed Sullivan Show, only to do it on Saturday nights with Howard Cosell. And right there you had at least two fatal errors. Saturday night isn’t the night that the family gathers around the TV after supper, the way they did for years to watch Ed. And Howard Cosell was many things — including, people forget, a man who brought a new honesty and maturity to sportscasting — but he wasn’t Ed Sullivan. Cosell wasn’t warm and friendly, and he lacked Ed’s credibility as an endorser of talented people.

And there may have been a third fatal error (maybe the Sullivan show had left the airways because the format had gotten stale and antiquated) and perhaps even a fourth (exec producer Roone Arledge was proficient in sports and news, not entertainment). The end result was a show that only had two things in common with Ed’s old show: It was done in the same studio and it was cancelled.

Ed had been cancelled after 23 years. “Humble Howard,” as some called him, was axed after four months. (Most histories say three.) The top ticket above is to the dress rehearsal of the first episode which aired September 20, 1975 and which tried to capture some of the excitement Ed had achieved by booking The Beatles. What the Cosell show had was an audience packed with screaming teenage girls and, on stage, The Bay City Rollers. Not quite the same thing. The other ticket above is for the next-to-last broadcast, the last being on January 17, 1976.

The whole effort is probably best remembered by its connection to another show that debuted less than a month later. Over at NBC, producer Lorne Michaels had wanted to call his new late night show Saturday Night Live but the name was taken so he settled for NBC Saturday Night. After the Cosell program went off, Michaels’ show took custody of the name as of its 3/26/77 broadcast.

Also, the Cosell series had a small regular comedy troupe of three performers — Bill Murray, Brian-Doyle Murray and Christopher Guest — who were billed as “The Prime Time Players.” It inspired the name of the comedy squadron on Michaels’ show, The Not-Ready-For-Primetime Players. And of course, all three men — Guest and the two Murray brothers — wound up in the cast of the NBC late night series at different times.

My most vivid memory of Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell is that one evening, Howard waded out into the audience to do a brief interview with two men who’d been invited to be there. They were Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman, who were then waging a public campaign to pressure DC Comics to come across with pensions and other financial assistance. The spot gave their cause a nice bit of publicity and it probably helped a little to shame DC into doing the right thing. So Howard, as dislikeable as he could be at times, did something nice. And it would have been even nicer if he hadn’t kept referring to Joe Shuster as “John.”