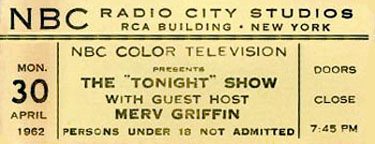

Tonight Show, The (1962)

Jack Paar hosted his final episode of Tonight on March 30, 1962. Johnny Carson had been signed to replace him but Johnny was still under contract to host Who Do You Trust on ABC and wouldn’t be free until later that year. So for six months, guest hosts helmed the late night show, starting with Art Linkletter. Among others who took a week or two were Soupy Sales, Jerry Lewis, Joey Bishop, Steve Lawrence, Groucho Marx, Arlene Francis, Mort Sahl, Jack E. Leonard, Hal March, Donald O’Connor and even Paar’s old sidekick, Hugh Downs, who stayed on as announcer for the transition period and hosted at least one week. The above ticket is from one of several weeks hosted by Merv Griffin. NBC had him signed to do The Merv Griffin Show in the afternoons, just to keep him around in case Johnny bombed.

The six months of temps are truly lost episodes. There are no known videotapes or kinescopes, and pretty much everyone has forgotten about the period. My fuzzy memory — I was ten at the time — was that some of the hosts did a pretty good job, perhaps auditioning just in case Johnny didn’t work out. Others figured they had nothing to lose and turned the show into one long commercial for their other endeavors. Reportedly, Carson watched a few broadcasts in the latter category and called NBC to complain that they were destroying the show he was going to be taking over. Dick Cavett, who had previously been a Talent Coordinator for Paar, was on the writing staff.

One other note: Although it was casually referred to as The Tonight Show, it was not called that until Paar left. The Steve Allen version was called Tonight, as was the Paar version for his first few years, after which it became Jack Paar Tonight and then The Jack Paar Show. But Tonight and The Tonight Show were used informally throughout those years. Some TV listings still called it Tonight long after it was The Jack Paar Show on the air. So if one wanted to split follicles, one could say that the first host of The Tonight Show was Art Linkletter.

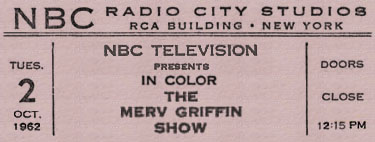

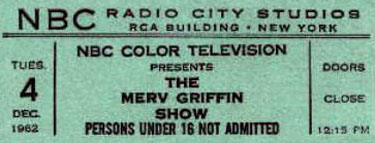

Merv Griffin Show, The (1962-1963)

In 1962 when Jack Paar decided to leave Tonight, several names were mentioned as possible replacements. Among them was a former band singer named Merv Griffin, who had recently been hosting the game shows Play Your Hunch for NBC and Keep Talking for CBS. He had also guest-hosted successfully for Paar and probably would have gotten the late night show, had NBC not opted to go with Johnny Carson. But just in case Johnny didn’t work out, NBC also signed Griffin and kept him in the bullpen. Merv hosted Tonight during the interim period after Paar departed but before Carson arrived. And then Merv started an afternoon talk show that debuted October 1, 1962 — the same day Johnny took over The Tonight Show.

As things turned out, Carson’s talk show succeeded but Merv’s did not. It was cancelled in less than a year. But Merv didn’t hurt for the experience. His deal with NBC had guaranteed that his production company could do a couple of game shows for the network. In short order, he was back on the air with Word for Word.

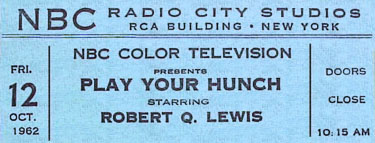

Play Your Hunch

Play Your Hunch was The Game Show That Would Not Die. It started on CBS in the daytime. They cancelled it after six months. It moved to ABC, again in daytime. They cancelled it after six months. Then it moved to NBC, where it lasted four years in daytime with occasional brief forays into nighttime. I don’t know why the above tickets from 1961 and 1962 describe a program that had been on the air since 1958 as “a new audience participation show.”

Merv Griffin hosted for most of the run, and the show was pretty simple. Two teams of contestants (usually husband-wife) would be shown little puzzles, usually involving three people coming out on stage or three objects being unveiled. The correct answer to the question would be one of the three choices, which were labelled X, Y and Z. If you guessed right, you got points. That was it.

One of Merv’s big breaks came about because Play Your Hunch was done live each morning from Studio 6B in what was then called Radio City Studios. Later in the day, long after Merv and his show were out of there, the studio was reset for Jack Paar’s late night show. Mr. Paar was a nervous, superstitious gent and when he was working at NBC, he usually declined to ride the elevators at Rockefeller Center. Instead, he would reach his office each morning by an intricate series of stairwells and short-cuts. His route took him through the usually-deserted Studio 6B but one day, he arrived at the studio much earlier than usual and found himself walking onto a broadcast of Play Your Hunch.

The studio audience went berserk and Paar, finding himself unexpectedly on live TV, attempted to flee. But Merv ran over and got a vise-grip on the bewildered star’s arm to keep him there so he could conduct a brief, funny interview. Paar swore he had no idea that his studio was being used by another program each morning. “So this is what you do in the daytime,” Paar quipped to Griffin, who had occasionally sung on Tonight.

Later, Paar admitted he was impressed with how Griffin had “milked” the accident for its maximum entertainment value by keeping him there. He gave Merv a shot guest-hosting Tonight and when that went well, it led to Griffin becoming a candidate to succeed Paar and also getting signed to do The Merv Griffin Show on NBC’s daytime schedule. Merv left the game show and Gene Rayburn took over for a month. Then NBC decided to put Match Game on later in the year, Rayburn went off to get ready to host that, and Robert Q. Lewis helmed Play Your Hunch until it went off in September of 1963.

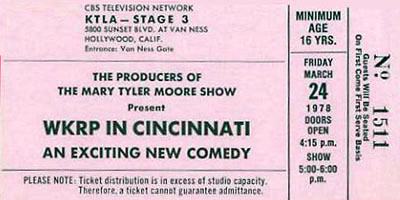

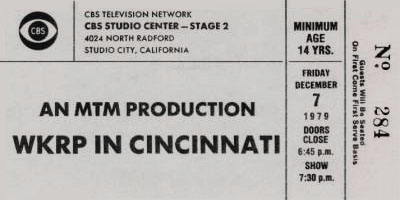

WKRP in Cincinnati

Most folks forget that WKRP in Cincinnati was one of the MTM shows and according to some who worked on the show, the MTM people wanted to forget it, as well. The series had a reasonable run (4 years, 90 episodes) and was nominated in three of its four seasons for the Emmy for “Outstanding Comedy Series.” But those who worked on the show said that the MTM execs — which I guess means Grant Tinker, mainly — didn’t like the show, didn’t mention it in interviews and did nothing when the network screwed with the scripts or moved the show repeatedly from time slot to time slot.

The show was taped — not filmed like most other MTM shows — initially at KTLA, far from the CBS Radford lot where other MTM shows were produced. When they moved to Radford, the producers thought that closeness might cause the MTM execs to welcome them into the family…but Tinker reportedly didn’t even walk across the lot to visit the set. Not only that but Mary Tyler Moore herself was even quoted in one newspaper piece as saying, “I wouldn’t watch it.” No, I don’t understand this attitude, either. It was a funny show with a good cast. I think they were just mad because they couldn’t understand the lyrics in the closing theme song…which were not, by the way, real words. Just gibberish.

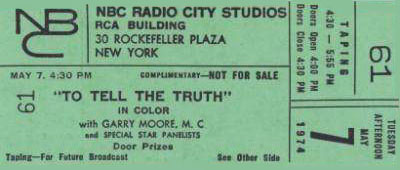

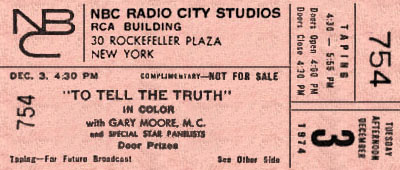

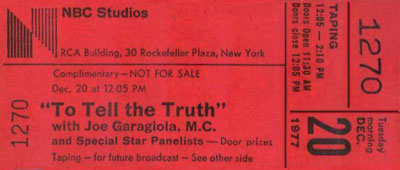

To Tell the Truth (1969-1981)

Garry Moore had a long, glorious career hosting game shows. You’d think someone would know how to spell his name on a ticket. This one was for the syndicated daytime version of To Tell the Truth, which ran from 1969 to 1981. Moore hosted until 1977 and then mysteriously disappeared. All of a sudden, Bill Cullen, and then Joe Garagiola were filling in for him “while Garry is off on a much-deserved vacation.” Audiences sensed something was wrong and began bombarding the show with mail asking what was really happening, and was the rumor true that Garry had died? No, it wasn’t — but the correspondents were right that something was wrong.

Moore had developed a cancerous node in his throat, and was off for a few months while it was removed and he got his voice back. He decided not to return to the daily or weekly grind and to retire but to deal with the rumors, he came back and hosted To Tell the Truth for one last time. His surprise walk-on at the beginning stunned the studio audience and they gave him one of the most enthusiastic, loving ovations ever on television, then later in the show fell properly silent as he explained about his operation and his retirement. Thereafter, Garagiola became the permanent host.

In deference to all the tobacco sponsors he’d had over the years — you can see him smoking incessantly on I’ve Got A Secret, brought to you by Winston cigarettes — Moore did not reveal that he’d had cancer. He died in 1993 and the cause of death was listed as emphysema.

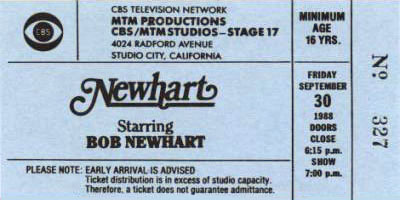

Newhart

I once asked Kim LeMasters, who ran programming for several years at CBS, if anyone ever came in, pitched him an idea and he bought it on the spot. He said it had happened twice. One was Magnum, P.I. and the other was Newhart. In both cases, the “pitcher” (in the case of Newhart, it was Barry Kemp) came in with a star the network wanted to work with and a format that was fully developed and perfect for that star. And the idea of this show, with Bob running an inn and putting up with odd neighbors and occupants, was pretty darn ideal for Mr. Newhart.

As you can see from the above ticket, it was done on Stage 17 at the CBS Radford lot, which was the same place where Bob did The Bob Newhart Show for 142 episodes. This one lasted 184, which must be some kind of industry record for one-two punches. (To balance, Newhart’s next sitcom — the one I worked on, of course — lasted 33 episodes, and the one after that lasted 22.) The early episodes of Newhart were done on videotape, as opposed to film. Bob, it turned out, decided he didn’t like the look of tape so they converted to film. If you think that sounds silly…hey, you go argue with 184 episodes.

A lot of people think the last one, in which it turned out the entire series was a dream of the character Bob played in his previous series, was one of the most daring, brilliant ideas ever on television. It’s certainly a contender.

All’s Fair

The premise of All’s Fair — a show which almost no one remembers — was that Richard Crenna played a very conservative political columnist in Washington, and Bernadette Peters played his lady friend who was, of course,very liberal. I only watched a few episodes but it seemed to me — like most political discussions in today’s non-sitcom world — a little too pat, in terms of everyone mouthing knee-jerk positions and coming quickly to realize the flaws in their position. Unlike the real world (except at the residence of James Carville and Mary Matalin), Crenna and Peters usually managed to find a way to resolve or compromise their arguments before bedtime. This show lasted for a year and went through a few storyline changes (and the addition to the cast of Michael Keaton) but it never quite caught on.

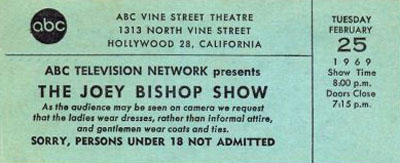

Joey Bishop Show, The (1967-1969)

For decades, ABC and CBS tried over and over to establish a berth in late night television and to compete successfully with Johnny Carson on NBC. In 1967, after giving up on a news-oriented discussion program called The Les Crane Show, ABC dropped Joey Bishop into the time slot with a 90 minute talk show that was pure, Tonight Show-style entertainment. Bishop was a natural choice: He’d served well as a guest host for Carson and for Jack Paar before him. And the public seemed to like him. They’d watched the previous Joey Bishop Show — a situation comedy — in sufficient number to keep it on the air from 1961 to 1965. On it, Bishop played a talk show host so, in yet another case of life imitating art, he became a real talk show host.

Bishop’s new show had many things going for it. Regis Philbin was a fine announcer and sidekick who sometimes managed to steal the spotlight from his boss. Johnny Mann was the bandleader and he gave the show a good sound. The whole thing emanated from Hollywood at a time when Carson was still based in New York. That — and Bishop’s many show biz friendships — seemed to guarantee a steady stream of big name guests, though operating on the West Coast did have one big disadvantage. As you can see from the ticket, The Joey Bishop Show taped in the evening. That meant a one-day delay in being broadcast. With so much in the news, Carson’s monologues and guest chats were becoming more topical and Bishop was lagging a day behind. If as sometimes happens in comedy writing, the same joke occurred to both writing staffs at the same time, Joey would be uttering it twenty-four hours after America had heard it from Johnny.

In fact, the biggest plus Bishop had when his show debuted on April 17, 1967 was that he wasn’t opposite Johnny Carson, who was then engaged in a battle with NBC over compensation and control. Johnny was off the air for several weeks, leaving The Tonight Show to a series of guest hosts — primarily country-western singer Jimmy Dean — and the late night audience to Joey. For a brief time, it looked like ABC was establishing its foothold in the time slot and that may have stampeded NBC into acceding to Carson’s demands, which they did. When Johnny returned to his natural habitat, Joey’s ratings dropped significantly. Thereafter, he trailed and the gap grew slowly wider…not that there weren’t moments when it looked like Joey was clawing his way back. Johnny took a lot of vacations, and they always gave Joey a little bump. And when his numbers dipped and rumors of cancellation began to swirl, Joey could usually manage to land a superstar guest and bring some audience back.

One of his highest ratings came after a taping when Regis Philbin abruptly announced that he was quitting the show. The one day delay worked to the show’s benefit that time. The news spread and much of America tuned in to hear Philbin announce — apparently stunning Joey — that the network had never wanted him in the first place and that he had endured too much criticism from them that he was dragging down the show. A few nights later, everyone watched again to hear Bishop announce that everything had been smoothed over, after which he welcomed Regis back to the show. The incident gave Joey two of the few nights he beat Carson but several TV critics suggested it was all an arranged stunt.

Finally though, ABC had to accept the reality of atrophying ratings. In late ’68, CBS announced that Merv Griffin would host an 11:30 talk show to commence the following March. Recognizing that this would split the already-small audience of folks who didn’t choose to watch Johnny, ABC decided to see if Dick Cavett could succeed where Bishop hadn’t. Sure enough, when Merv went on, Joey’s numbers plunged. Bishop didn’t even host the final weeks of his program, leaving it to guest hosts until it was replaced by Cavett in May. Not long after, Carson enlisted Joey as his main guest host and Joey wound up sitting behind Johnny’s desk 177 times, which was the house record until 1983 when Joan Rivers was named “permanent guest host.” It was a great example of the old show business maxim” “If you can’t beat ’em, fill in for ’em.”

Big Eddie

Sheldon Leonard spent most of his early acting career playing gangsters, race track touts and other shady individuals. In the sixties, he turned to producing and directing but could always make time for the occasional mobster role. In 1975, he even starred in a short-lived situation comedy about a former tough guy. Big Eddie featured him as Eddie Smith…and one suspects the innocuous surname was chosen to make sure there was no connect to any ethnic group. Smith had made the move from the rackets to an almost-respectable life operating a New York sports arena. Past associates and old, unfinished business from his past life had an annoying way of turning up, though all Eddie wanted to live an honest life with his spouse (a former stripper played by Sheree North) and their granddaughter (played by 12-year-old Quinn Cummings, who would go on to steal the movie, The Goodbye Girl, two years later). Eddie also had a thing about bubble baths and could often be found luxuriating in one.

The show went on the air August 23 of 1975 with solid writing/producing from Bill Persky and Sam Denoff, who’d worked with Leonard on The Dick Van Dyke Show among other triumphs. CBS didn’t seem to have a lot of faith in it. After only three broadcasts, they moved it to another night — never a promising sign — and wound up shutting it down after only ten episodes. It was a bad year for Persky and Denoff, who were simultaneously launching a sitcom for NBC called The Montefuscos. They made thirteen of those but the network only aired eight or nine of them.

I remember Big Eddie as a pleasant show that kept hitting the same note over and over…Eddie trying to convince people that he’d changed and had put the old days behind him. I also seem to recall that it was never quite clear how nefarious those old days had been; like early on, the idea had been that he’d been the kind of hood who had people rubbed out but someone — the network or the producers or someone — had said, “No, then he’d be a murderer who got away with it and audiences wouldn’t like him.” So they softened his backstory down to the point where he was almost a businessman who’d occasionally dealt with the wrong people, thereby removing what might have been more interesting about Eddie Smith. Still, it was a nice, albeit short star turn for Sheldon Leonard, who was very good in the role. He didn’t do much acting after that but did manage to get cast as J. Edgar Hoover in a TV-Movie just before he retired. That might have been the sleaziest character he every played.

Lloyd Thaxton Show, The

Lloyd Thaxton was a fixture of Los Angeles TV for much of the sixties, primarily for an afternoon dance party show not unlike Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Thaxton’s had a couple of different names — Lloyd Thaxton’s Record Shop, The Lloyd Thaxton Show, Thaxton’s Show and others — but they were all Lloyd with a bunch of local teens, a few musical guests and a lot of clever games and stunts.

Working with almost no budget in the shabby studios of KCOP, Channel 13, Thaxton came up with ingenious ways to keep viewers interested when all he did was to play current hits and let kids dance to them. Recording artists would come on and lip-sync their records…and I always liked the fact that they usually wouldn’t assume we thought they were playing and singing live. They’d own up to the miming…and if the performer didn’t seem to know the lyrics to their own song, as was sometimes the case, Thaxton would run over and mix up the cue cards to throw them further off. He’d also get up himself and lip-sync to a Bobby Darin or Bobby Vinton record. Teenagers who showed up with tickets like the one above would dance or participate in games but Thaxton would also select some of them to get up and pretend to be Chad and Jeremy or Sonny and Cher or someone and lip-sync to those performers’ hits. Sometimes, Lloyd would take a photo of a singer or an album cover with a close-up of the artist’s face, cut out the mouth area, insert his own lips and “sing” the song that way.

What made it all work was Thaxton himself. He was unpretentious, self-effacing and funny…more than could be said for most of those who went up against him with similar shows. There were a number of them because they didn’t last, while Thaxton went on and on…all the way until around 1968 when all the local stations were getting out of producing their own shows. For the last few years, he was also syndicated and the show did well in other cities, as well. The trouble was that with the rise of afternoon talk shows and stations expanding their news broadcasts, there were no time slots for it. Thaxton moved on to host a few game shows that didn’t last, then moved to the other side of the camera as a producer and writer.

I used to see him in the hallways at NBC when I was writing a show that taped there and he was producing a series with consumer advocate David Horowitz. He always looked so busy, rushing to some meeting or something, that it was awkward to stop him and tell him how much I’d enjoyed watching his show. Finally one day, I approached him and got about six words into what I wanted to say before someone came running down the hall to tell him there was an urgent phone call. He excused himself and ran off and I never got to finish. I thought of calling his office and leaving it on his voice mail but I was afraid he’d just lip-sync to it.