Tattletales

Tattletales evolved out of an earlier Goodson-Todman game show called He Said, She Said. In this new version, three celebrity couples competed to see who knew the most about his or her mate. The audience was divided in thirds and each celebrity couple was playing for one segment of the audience, which would divide up the celebs’ winnings. The show paid off then and there: As audience members left, they were handed a check from an automatic check-writing machine. Each “rooting section” had 122 people in it, and the winning celebrity couple’s section might split around $1200 while the losing couples might each have earned $300-$400 for their section. So if you went and sat through the taping of a few episodes, you might take home twenty bucks — not a huge amount, but twenty bucks more than any other show paid you to sit there and applaud. There were homeless folks in the area who went to Tattletales tapings and made enough money to eat for a few days and there were merchants located around CBS who put up signs that said, “We cash Tattletales checks.”

Bert Convy was the host of this series that ran from February of 1974 to March of ’78, then returned to the air in January of ’82 and ran ’til June of 1984 — not a bad run and there was a syndicated version, as well. A few years ago, when Game Show Network acquired the series, they did promos that emphasized the rather amazing percentage of celebrity couples who’d appeared together on Tattletales and divorced soon after.

New Dick Van Dyke Show, The

The original Dick Van Dyke Show left the CBS airwaves in 1966 and its two main stars — Mary Tyler Moore and Mr. Van Dyke — plunged into movies, both with disappointing results. In 1969, they co-starred in a variety special, Dick Van Dyke and the Other Woman, that led to offers to return full-time to television. Dick said no and returned to his new home in Arizona. Mary said yes and The Mary Tyler Moore Show went on the air and became a large hit. This prompted CBS to up its offer to Van Dyke…but Dick was happy in Arizona and not interested in returning to L.A. to do a new series. The solution was to remodel and upgrade a studio near Van Dyke’s new desert home and to do the show there…the first network prime-time TV show ever filmed in Carefree, Arizona and (one suspects) the last.

It was titled The New Dick Van Dyke Show though they sometimes omitted the “new,” as you might note in the tickets above. There’s no “new” on the second season ticket but there is on the third season ticket. The first two years were produced in Arizona with Carl Reiner running things, and found Dick playing Dick Preston, a talk show host at a mythical Phoenix TV station, KXIU. Hope Lange played his spouse and suffered the unenviable fate of having most of America say, “They don’t have the same chemistry he had with Mary.” Well, at least the guys at CBS said that, and as her role was downplayed and more of the action centered around the talk show, rumors circulated that Ms. Lange wanted out.

She stayed but one attempt to build an installment more around her relationship with Dick drove Carl Reiner away. Near the end of the second season, CBS rejected an episode in which the Prestons’ young daughter accidentally walked into the bedroom of Mommy and Daddy while Mommy and Daddy were having sex. This happened off-camera and Reiner insisted the scene was tastefully done, very funny and that it had been properly vetted by consultants whose opinions should be honored. CBS refused, the episode never aired and Reiner quit. The series itself was almost cancelled then but Van Dyke had a firm three-year contract and CBS had a hole in its schedule that seemed to need the show.

For what turned out to be its final season, the no-longer-new New Dick Van Dyke Show moved to Hollywood where a new creative team did a remodelling job. Apart from Ms. Lange and Angela Powell (the actress who played their daughter), the entire supporting cast was let go. Dick Preston became an actor on a daytime soap opera, and new cast members were added. They included Richard Dawson (who played a TV cooking host not unlike Graham “The Galloping Gourmet” Kerr), Chita Rivera, Barry Gordon, Henry Darrow, Barbara Rush and Dick Van Patten. Ratings went up but Van Dyke’s interest in the whole project went down and at the end of the season and after completing 72 episodes, he announced he was done with it and with series television. And he never did another series again except for Van Dyke and Company (1976), The Van Dyke Show (1988) and Diagnosis Murder (1993-2001).

Family Feud (1988-1995)

Ray Combs was a nervous little man who turned up in the Los Angeles stand-up comedy circuit in the early-to-mid eighties with an absolutely terrible act — the kind of thing a non-professional might whip up for the Rotary Club’s annual pancake breakfast. But he seemed like a nice guy and he sure tried hard. And if his act wasn’t good enough to get him work as a real stand-up, it did land him some gigs doing audience warm-ups — a job that often serves as a kind of consolation prize for those denied real careers in comedy. Combs wasn’t too funny but he was so likeable and eager to succeed that studio audiences took to the guy, and he started developing some “buzz.” Jim McCawley, who was then booking comedians for Johnny Carson took an enormous gamble and put him on in 1986.

The act was still unsophisticated, and more than a few veteran stand-ups remarked that of all the performers they couldn’t imagine would ever make The Tonight Show, Combs was near the top of the list. Amazingly, he not only got on but he did well. (I saw him that evening and it seemed like the audience didn’t find him funny but thought he was trying so hard he deserved a huge ovation.) The spot got him a lot of attention and some high-profile auditions.

Two years later, Mark Goodson wanted to revive the game show Family Feud for syndication but needed a new host — preferably someone who’d be a lot more cooperative and inexpensive than the original emcee, Richard Dawson. They almost went with Joe Namath but when negotiations got difficult, Combs got the job. The above tickets would have been to some of his first shows, and things went well enough for a few years. But shortly after Mark Goodson passed away, ratings took a nosedive. In an unsuccessful effort to save the program, Jonathan Goodson (who’d taken over his father’s company) fired Combs and brought back Dawson, who didn’t fare any better. From that point on, the life and times of Ray Combs took a downward spiral — bad investments, other shows that didn’t make it, a bad car accident that left him with chronic back problems. Deeply depressed, he was finally placed in an institution where in 1996, he took his own life. He only had a few years of his dream but as others have pointed out, that’s a lot more than some people get.

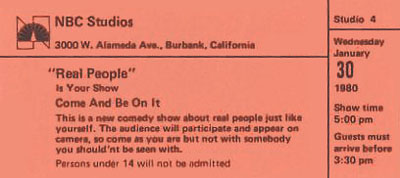

Beat the Clock (1979-1980)

This was a revival of an earlier Goodson-Todman show — one that, as I mentioned here, I never liked. I didn’t like the original with Bill Collyer. I didn’t like the 1969-1974 revival hosted by Jack Narz and later by Gene Wood. I didn’t like this version, which was hosted by Monty Hall. And though I never saw the short-lived 2002 revival hosted by Gary Kroeger, I’m pretty sure I didn’t like it, either; not if it consisted of people having to do silly stunts before a clock ran down.

Audiences didn’t warm to the 1979-1980 version either — not on TV and not even in person. You can see the desperate attempt to bolster ratings in the above tickets. The show changed from Beat the Clock to All-Star Beat the Clock, which it did by bringing celebrities in to attempt the stupid timed feats. Needless to say, “all-star” was a bit of an overstatement. You don’t get real stars to go on television and attempt to catch marshmallows in their ears while sitting on a skateboard and balancing a bowl of live guppies…in 45 seconds. The show also tried the Tattletales gimmick of having the putative celebrities play for the studio audience, thereby helping to fill the seats. Rumor has it they still had trouble filling the house. Even the homeless folks decided they’d rather go hungry.

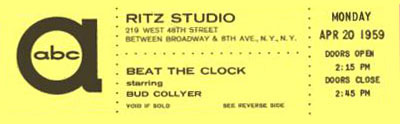

Beat the Clock (1950-1961)

Everyone has a couple of TV shows they can’t stand. Among mine are the various versions of Beat the Clock, a program built on the principle that there’s always someone who’ll humiliate themselves for a free blender. Bud Collyer was the genial host of the original version which started on radio in 1949, moved to CBS television in 1950, then shifted to ABC from 1958 to 1961. Even though Mr. Collyer had supplied the voice of Superman on radio and for animation, I was never able to warm to him as a TV host. On Beat the Clock, he got contestants to perform silly stunts while a big clock ticked off their deadlines…and there was something very condescending about the way he instructed the people in their assignments and giggled at their failures.

The Ritz Theater was an appropriate place to do Beat the Clock, as it was built on a deadline in 1921. The Shubert organization gave the contractor a mere sixty days to erect the place and his crew managed to do it. A week later, its first attraction (two short plays by John Drinkwater) went into rehearsal. It housed now-forgotten plays until 1943 when it was converted to a radio studio and later, a television facility. It closed down in 1965 and remained dark until it was purchased, renovated and reopened in 1971. In 1990, it was renamed the Walter Kerr Theater, honoring the famed Broadway critic. Over the years, dozens of theatrical productions played there, every single one of which was more entertaining than Beat the Clock.

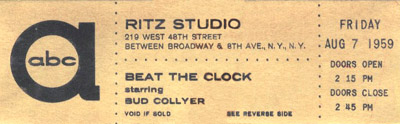

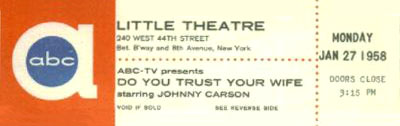

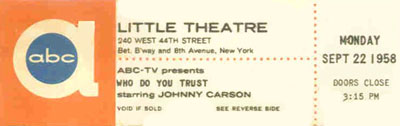

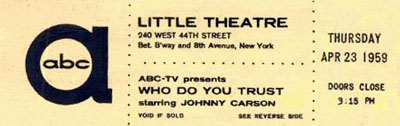

Who Do You Trust

TV history books will tell you that Edgar Bergen (and wooden friends) hosted a prime-time game show called Do You Trust Your Wife? from 1956 to 1957. They will further tell you that when it shifted to daytime on July 14, 1958, its name was changed to the ungrammatical Who Do You Trust (should have been Whom and had a question mark) and that Bergen was replaced by Johnny Carson. The above tickets tell a different story. Here we see Johnny hosting the daytime version in January of ’58 and it’s still called Do You Trust Your Wife? Perhaps the name change is what occurred on the July date. On the September 22, 1958 ticket above, the name of the show is in a typeface other than the one normally used then on ABC tickets. That would suggest someone had made a quick fix on the printing plates to change the name of the program.

Writing the name of Carson’s game show without a question mark was symbolic of the program, which was a quiz show that never got around to asking many questions. Like Bergen’s version and Groucho’s You Bet Your Life, the quiz format was just an excuse for the host to banter with contestants and, in Johnny’s case, to engage in demonstrations. A belly dancer would come on to play the game and before they got to that, she’d give Johnny a lesson in her craft. It all honed and demonstrated Carson’s fine skills for making an interview interesting and participating in stunts — two of the three essential skills (the other being the monologue) that he’d display on The Tonight Show.

Occasionally, the game show got randy. Tuesday through Friday, Johnny would do the show live. On Fridays, he’d also tape a show that could air on Mondays so he and the crew could have a three-day weekend. After doing the live Friday show and before taping Monday’s, he and announcer Ed McMahon would repair to a nearby tavern for dinner and drinks, often resulting in an alcohol-enhanced taping that would be looser and dirtier than the norm and, of course, funnier. It all earned Johnny The Tonight Show, though not without a wait. When he was signed to replace Jack Paar on the late-night show, he still had six months on his Who Do You Trust contract, and that show’s producer, Don Fedderson, saw no reason to let him out early. The Tonight Show endured six months of guest hosts while Johnny hosted his afternoon program under duress, cracking jokes about ABC holding him prisoner. In actuality, it was not ABC but Fedderson, who knew that his show would not long survive the loss of Johnny…and it didn’t. Carson was finally replaced by comedian Woody Woodbury, ratings on Who Do You Trust plunged, and that was the end of that.

Danny Kaye Show, The

Danny Kaye was one of those entertainers who was almost universally loved by audiences when he was performing, and despised by those around him when he wasn’t. His 1963-1967 variety show was pretty wonderful, as I recall — kind of a mid-point between the Sid Caesar and Carol Burnett shows. Half his writing staff had worked for Sid. Most of the others would work for Carol, as would co-star Harvey Korman. Burnett, whose show went on just as Kaye’s was going off, would even tape in the same studio. Of interest on the above ticket is the rubber-stamped proclamation, “Special — No Seats Reserved.” You see that on a lot of tickets and it’s sometimes pretty meaningless. They stamp “special” on your free tickets and you think you’re somehow privileged and will get V.I.P. treatment if you use them. What you don’t know of course is that everyone else also has a “special” ticket. It can also be a way of composing the audience with preferred types. For example, they want to limit the number of senior citizens in the house so they pass out the “special” tickets via means that they know are likely to reach a younger crowd and make a point of seating them first and in the front.

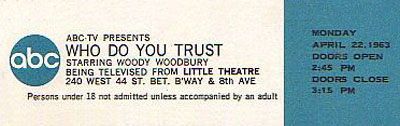

Red Skelton Show, The

Tickets to TV tapings are free, of course. But they could have made a fortune charging to see Red Skelton rehearse; that is, if they raised the minimum age to 21. As I explained in this article, Mr. Skelton’s dress rehearsals consisted of ignoring that week’s scripts and telling dirty jokes to the crew and a contingent of CBS secretaries and employees who filled the audience. And here are the key questions: If you were the maker of Pet Evaporated Milk, would you really want to publicize that you also made Johnson’s Wax? Just how do you benefit from connecting those two products in the minds of the American public? And what the heck ever happened to Brian Donlevy?

There’s some odd terminology on two of the above tickets. Skelton, when he did his show at CBS, would do a “preview” performance on Monday night for a live audience — not to be confused with his ribald dress rehearsals, for which there were no tickets. Then the script would be revised and rehearsed for a Tuesday evening taping. But in most cases, a ticket that says “a special preview” is a ticket to watch a tape or film of a show that was shot without a live audience. Some shows have done that — shot without the public present, then brought an audience in, shown them the program and recorded their laughter and applause to dub into the show. That doesn’t seem to have been the case with the second and third tickets above, especially the one that says “preview performance.” Both were probably tickets to watch Red Skelton and his guests do the entire show live…but they don’t look it.

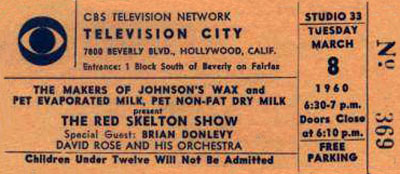

Real People

Real People, which some might call the first prime-time TV “reality show,” debuted on April 18, 1979. So I’m not sure why a ticket for a taping more than nine months later is composed as if attendees had never heard of it. Nevertheless, this is one of the few TV tickets I’ve ever seen that felt it had to explain a little about the show and even make a joke, warning people not to show up “with somebody you should’nt [sic] be seen with.” For those who don’t remember, the idea of Real People was that the show’s correspondents would just spotlight and salute interesting folks around the country. Produced by George “Laugh-In” Schlatter, the series was enormously popular for most of its five years and briefly made stars out of some of those it covered, and spawned a short-lived spin-off, Schlatter’s Speak Up, America. Also, one of the hosts, John Barbour, was inspired to go out and sell something called That @&$# Quiz Show.

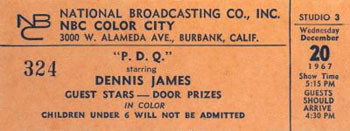

P.D.Q.

P.D.Q. was a fringe-time afternoon game show on NBC. “Fringe-time” means it was scheduled late in the afternoon and not every network affiliate carried it, so in some cities it was syndicated to non-NBC stations. The premise was that you had two teams, and at times they’d be one celebrity and one civilian. One member of each team would go into a little booth while the other member would race against the clock, running back and forth to put letters up on a board that would spell out a word or phrase. The person in the booth would have to guess the word or phrase based on seeing some but not all of the letters, and the team which “got it” in the fewest number of seconds would get the points. It was kind of like someone said, “How can we rip off Password but make it more physical?” Presiding over the game when it aired from 1965 to 1969 was Dennis James, the Iron Horse of TV game show hosting. Not long after it went off, Lin Bolen took command of NBC’s daytime game show lineup and, legend has it, she decided she didn’t want any of her programs hosted by “old men like Dennis James,” the theory being that housewives wanted someone hunkier to look at during the day. When the decision was made in 1973 to revive P.D.Q., it was retitled Baffle and Dick Enberg came in to host.

On the above ticket, one can see many indicators that P.D.Q. had trouble filling its studio audience: The long lead time between when they wanted you there and when they did the show, the door prizes, the low minimum age, etc. An awful lot of people who went to see them tape P.D.Q. probably arrived at NBC that day hoping to see something else.