Krofft Superstar Hour

I was actually one of the writers for this one, which was produced for NBC’s 1978 Saturday morning line-up by Sid and Marty Krofft. That season, the whole schedule was pretty much a disaster so after a few weeks, they switched some shows around, dumped others and the Krofft Superstar Hour was chopped down to a half-hour called The Bay City Rollers Show. In its shortened form, it stayed on the NBC Saturday morning schedule for a couple years of the same thirteen episodes being rerun over and over and over again. (I don’t think half of the last two hours we produced ever even aired.)

The show featured The Bay City Rollers and an all-star roster of characters from past Krofft shows: H.R. Pufnstuf, Witchiepoo, Seymour the Spider, Stupid Bat, Hoodoo (the villain from Lidsville, played on our show not by Charles Nelson Reilly but by a gent named Paul Gale, who did a darn good impression of him) and others. Jay Robinson, who’d portrayed Dr. Shrinker on the series of the same name, and Billy Barty, who played his assistant, played identical characters under different names. Also in the cast were Louise DuArt, Sharon Baird, Mickey McMeel, Patty Maloney, Van Snowden and voice actors Lennie Weinrib and Walker Edmiston. This show should not be confused with The Krofft Super-Show, which was on ABC a season or two earlier, but quite a few books on TV history don’t seem to know the difference.

When I signed on to work on the show, it was to have been hosted by ABBA — or so said a powerful agent who swore he represented that group and would deliver them. ABBA was at a low point it its/their career and reportedly eager/willing to do a kids’ show for American TV…but negotiations broke down and we instead got The Bay City Rollers, who were on a similar downturn. Our show was, in fact, the “last hurrah” of the group as composed primarily of the original Rollers. Their Scottish accents and awkwardness delivering intros and comedy material had a certain charm, even if it rendered much of what we wrote unintelligible. Still, I got along great with the guys even though they weren’t getting along so well with one another. At the time, one of them was suing the others, so a certain tension hung over the set.

We had an interesting technical problem on the show, in part because the membership of the Rollers had changed from time to time. Almost all the musical performances consisted of the Rollers lip-syncing to records they’d made a few years earlier…and in one or two cases, guys who were currently in the group were performing to recordings that hadn’t involved them, and they were mouthing the words to someone else’s voices. That made their lip-sync work less convincing than it otherwise might have been. Even when a musician performs to his own track, it is not uncommon for them to be a fraction of a second behind the audio so when you can, you go in and slip the picture a few frames later to compensate. Our editors found that they couldn’t do this easily with the Rollers. All five of the guys were moving their lips a quarter of a second late but the drummer, Derek, was right on the beat. Director Jack Regas, who’d done hundreds of hours of musical numbers for TV, said he’d never seen anything quite like it. Even Derek was a tiny bit behind with his singing but his sticks hit the drum in absolute precision…so if we’d moved the vocal tracks to put the lip movements in sync, the visual of him drumming would have been off. The post-production people had to go in and slide the picture only on angles where you couldn’t see Derek…and on shots of him playing and singing, they had to decide which of the two to let be out of sync. They usually opted to keep the drums in time.

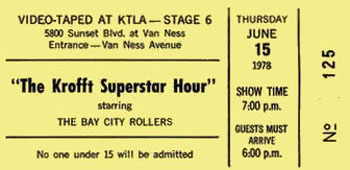

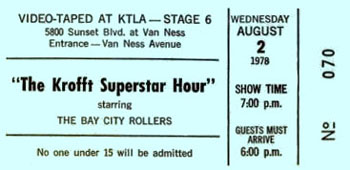

The moment tickets like the above were made available, they were immediately gobbled up by a squadron of teenage girls who staked out the studio every day, and occasionally found their way to a house up in Laurel Canyon where one faction of the Rollers was staying. The writers took turns doing the audience warm-ups for the tapings — the easiest job ever in show business. You just had to walk out and say the name of one of the Rollers and the girls in the bleachers, many of whom were clearly under the minimum age listed on the tickets, would scream themselves into a frenzy. (By the way: Industry legend, which is so often wrong, said that Stage 6 at KTLA was where Al Jolson filmed The Jazz Singer in 1929. Longtime TV producer Joel Tator notes that Stage 6 wasn’t even built at the time, and theorizes that Mr. Jolson actually performed on what is now Stage 9. Either way, when I worked there, everyone told us it was “Where Jolson made The Jazz Singer” and one got the feeling the place hadn’t been cleaned much since then.)

Bozo the Clown

Childrens’ records were big business in the forties and fifties, and some of the best were issued on the Capitol label. In 1946, a writer-producer for Capitol named Alan Livingston created the all-time superstar of the genre, Bozo the Clown, and issued the first of many records narrated by Bozo and chronicling his globe-spanning adventures. The material was cleverly-written with full orchestrations and the vocal talents of the original Bozo, Vance “Pinto” Colvig. The multi-talented Mr. Colvig had actually worked as a circus clown in his youth, but had more recently made his career as a cartoon writer and voice actor. He provided the sound of, among other great animated characters, Mr. Disney’s Goofy.

The Bozo records were a huge hit, leading to toys and merchandise, and to Colvig getting painted up in Bozo make-up for personal appearances. In 1949, he became one of the first TV personalities when he hosted a kids’ show on Los Angeles TV for a time. In the years following, other actors were recruited to play Bozo in a wide array of venues and one of them, Larry Harmon, came up with an idea. In 1956, together with a band of investors, he purchased the right to license and package Bozo TV shows across the country. Eventually, Harmon would acquire all rights to the World’s Most Famous Clown and build an industry around him.

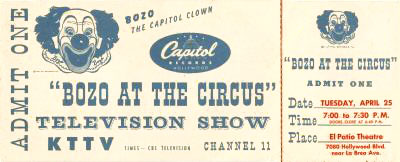

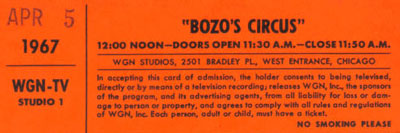

The way it worked was that local TV stations throughout the U.S. would license the right to produce a Bozo show in their city, usually employing a local actor who would be properly trained by Harmon’s crew. He would don the rademarked clown make-up, and he’d play games with kids, do little comedy bits, and introduce the Bozo cartoons that Harmon’s animation company produced. The programs went under various names — Bozo’s Circus, Bozo at the Circus, Bozo’s Big Top, et al.

The two most notable franchise operations were on KTLA in Los Angeles, where Vance Colvig, Jr. (son of Pinto) stepped into his father’s oversized shoes from 1959-1964, and WGN in Chicago, where local producers pulled out all stops. Catering to an audience of both kids and adults, the WGN program began in 1961 and featured a live 13-piece band and top circus acts from around the world. A gent named Bob Bell was Chicago’s Bozo until ’84, whereupon comedian Joey D’Auria stepped into those immense shoes and kept folks laughing until the show finally ended in 2001. This ticket is from 1967, which was around the time the show hit its peak in popularity, even spawning a prime-time spin-off called Big Top. (Thanks to George Pappas of WGN for some corrections to this listing.)