Chevy Chase Show, The

This was not a good idea. Chevy Chase had a sky-high TVQ score, TVQ being a survey that networks subscribe to. It tracks many things but mainly how well-known someone is and how well they’re liked. At the time, Mr. Chase’s TVQ score on both counts was a lot higher than most of the names you’d have come up with if you were a Fox executive and they asked you who should host a late night show for them.

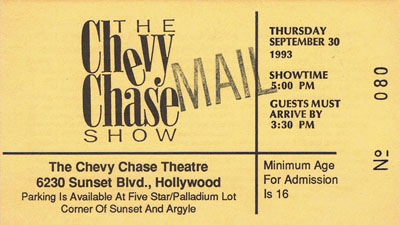

Mr. Chase was signed for a huge sum of money. The show went on the air September 7, 1993. Four weeks later, its cancellation was announced and then Chevy did one more week, most of which was spent joking about how poorly things had gone. Fox had guaranteed advertisers a tune-in of six million viewers but even the show’s first week hadn’t reached that number, coming in around three million. Before long, they were down to two. Within Fox, two reasons were usually given for the failure. One was that no one ever had an idea what would make Chevy’s version of The Tonight Show different from, say, the one Jay Leno was doing over at NBC under that name. The other reason was that Chevy was really more interested in his movie career and wasn’t especially committed to the venture. Whatever the reason, the show’s quick demise was predicted by critics from Day One.

Fox lost a lot of money. Along with what they paid Chase and the “make goods” (free commercials) they had to give to advertisers to make up for the ratings shortfall, there was the money spent to secure the Aquarius Theater on Sunset Boulevard and refurbish it into The Chevy Chase Theatre. Then five weeks later, they had to turn it back into the Aquarius. The building had once been the famous Earl Carroll Theatre, famed for its slogan, “Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world.” It closed on 1948 when Mr. Carroll was killed in a plane crash and then reopened in 1953 as the Moulin Rouge. It went through many names and owners after that and in 1968 became the Aquarius when it was the home of the Los Angeles production of the tribal rock musical, Hair. Today, it’s owned by Nickelodeon that has some of its offices and production facilities on the premises.

Pat Sajak Show, The

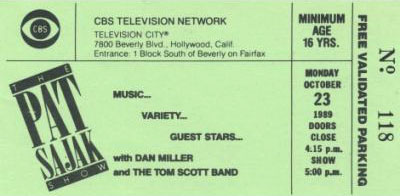

When CBS tapped Pat Sajak for a late-night talk show in 1989, a lot of industry folks wondered about the selection. He seemed awfully lightweight to compete against the mighty Johnny Carson. Then again, Sajak was the host of the enormously popular game show, Wheel of Fortune…and Carson himself had gone from hosting a game show to hosting The Tonight Show. Later on, everyone would say, “We knew it would never work” but not many were predicting that before Sajak’s debut on January 9 of that year.

Initial ratings were strong the first week, less strong the second…and by the time the first month was out, all talk of knocking Johnny off his throne had ceased. Most critics felt the show was Johnny Lite — too much the same format only not done as well. Within CBS, the complaint was that Sajak wasn’t giving it his all; that he still regarded hosting Wheel of Fortune as his “real” job and that hosting a 90-minute late night series was something he did in his free time. Sajak had given up hosting the daytime Wheel of Fortune but had kept the much more lucrative evening syndicated version.

In October of 1989, the show was cut from 90 minutes to an hour. Several CBS affiliates had bumped it to a later hour or were not carrying it at all…and from October on, that was happening at an accelerated pace. It became less a question of whether it would be cancelled as when. Sajak began working four days a week or skipping weeks completely and the show had a succession of guest hosts who were more or less auditioning for the time slot. By February of ’90, CBS was reportedly renewing the show a week or two at a time and on April 13, the last one aired with guest host Paul Rodriguez.

The show was regarded as a large failure but its initial tune-in did convince CBS that it was viable to compete with Carson; that they’d merely picked the wrong guy to do it. They began quietly scouting for the right guy and soon made an offer to Jay Leno, who was then Carson’s permanent guest host. When Leno instead opted to sign a contract with NBC that guaranteed him The Tonight Show upon Johnny’s eventual retirement, CBS went after David Letterman. He did a lot better in the time slot.

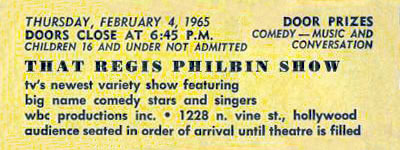

That Regis Philbin Show

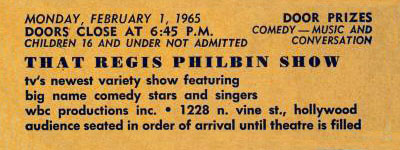

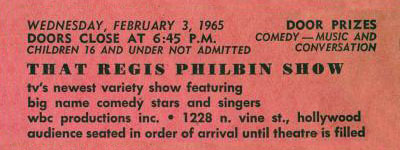

Regis Philbin got his start in broadcasting as a writer for the local news at KCOP TV in Los Angeles. His first on-air opportunity came at a station in San Diego and that’s where he was offered his own talk show. Steve Allen had been doing a syndicated show for the Westinghouse Broadcasting Company and when it went off in 1964, Westinghouse hired Philbin, moved him back to L.A. and offered That Regis Philbin Show to the many stations that had been programming The Steve Allen Show. Some took it, some didn’t…and then those that did began dropping it and That Regis Philbin Show ended in three or four months (accounts differ). Philbin bounced around between small TV and radio jobs until April of 1967 when he was hired as the sidekick on The Joey Bishop Show which ran late night on ABC and which was done from the same building as Philbin’s failed syndicated series. It was the first of many comebacks for the man who would eventually log more hours on television than anyone else.

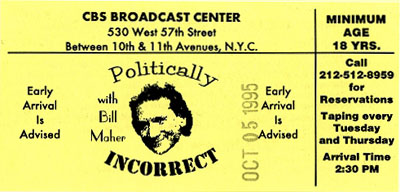

Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher

Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher debuted on Comedy Central on July 25, 1993. The format was simple: The host and four people sat around and discussed what was going on in the world. Maher opened each show with a brief monologue, then turned to his panel, which often included comedians and high-profile political figures. It was sometimes difficult to tell them apart.

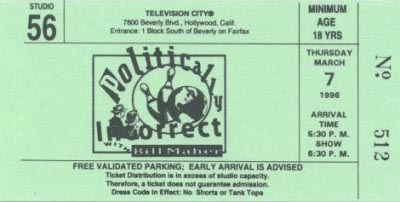

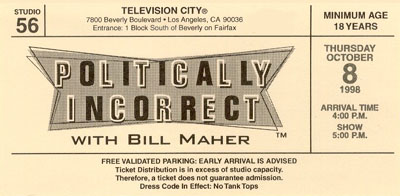

The series quickly built up a following, due mainly to Maher’s skill for keeping things moving and funny. His ability to ask tough questions (and to pointedly repeat them when guests evaded) made it interesting, and even some who abhorred his Libertarian/Atheist viewpoints admired his candor and showmanship. In ’97, ABC decided the series would make a great follow-up to Nightline and the show moved over, changing only in a few cosmetic ways, continuing to offer rowdier conversation than one usually finds on a network. It went that way until shortly after the attacks of 9/11/01 when Maher made a comment that said that whatever the suicide pilots were, it was wrong to describe them as “cowards.”

In hindsight, that was a mild and inarguable statement…but at the time, it caused protests, rebukes from the White House, advertiser desertion and, ultimately, ABC dropping the show. It has been suggested that they were already uncomfy with Maher’s outspoken manner and were looking for an excuse to lop him off their schedule. Whatever the thinking, he was axed in July of 2002 but soon resurfaced with Real Time with Bill Maher on HBO.

Politically Incorrect did its early shows (usually taped, occasionally live) from CBS Broadcast Center in New York but soon relocated to CBS Television City in Hollywood, the better to secure show biz guests. No matter who was airing it, it was done there, and Real Time is also presently done from CBS Television City.

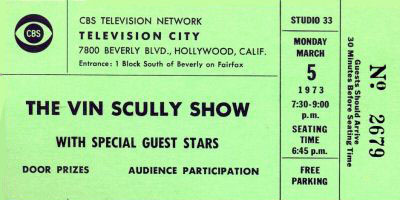

Vin Scully Show, The

In 1973, CBS tried to compete with the popular afternoon talk show then hosted by Mike Douglas. Their candidate to take on Mike? Vin Scully, then (as now) the voice of the Los Angeles Dodgers…a man often called the best sportscaster in the business.

Scully was much-loved in Southern California and a seasoned broadcaster. The only argument against him as the host of such a show was that when summer rolled around, he’d be off calling play-by-play and unavailable to tape shows on a daily basis. Reportedly, the folks at CBS thought he was such a good candidate for the post that they decided not to let a little thing like that dissuade them. The show went on the air in January of ’73 (January 15 to be exact) and the thought was that they’d worry about conflicts in Mr. Scully’s schedule later.

As it turned out, it wasn’t necessary. Scully’s show only lasted thirteen weeks, exiting the CBS daytime lineup on March 23 with new game shows taking over the time slot. The Old Redhead, as some called Scully, wasn’t all that comfy interviewing folks who didn’t have a good fastball. When sports figures came on, he was fine. With comedians and movie stars? Not so fine. So Vin scurried back to the broadcast booth and the show was quickly forgotten.

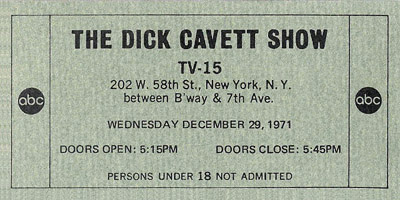

Dick Cavett Show, The (1969-1974)

There have been quite a few programs called The Dick Cavett Show but with the exception of one ill-fated attempt at variety, they were all pretty much the same: Cavett sitting around, talking to interesting people. Cavett had previously worked as a writer for both Jack Paar and Johnny Carson, and he seemed to have absorbed the better qualities of each without the worst. He had Paar’s love of conversation but not the same penchant for feuds and self-pity, and he had Carson’s comic instincts without the occasional leering qualities. On the downside, he sometimes had an “I’m smarter than you” attitude that alienated some viewers and there was often the subtext of, “Look at all the famous people I hang out with.” Neither was fatal and on the whole, Mr. Cavett did a very fine show.

It’s unfortunately lumped in with the long list of talk shows that tried to compete with Johnny and failed, and some of the articles about Cavett make it sound like he was in and out of the time slot in thirteen weeks or less. He was actually on for almost five years which, given how highly competitive it was to be on then at 11:30, is quite an accomplishment. The show was also critically-acclaimed and won awards at a time when that could be said of very little on ABC.

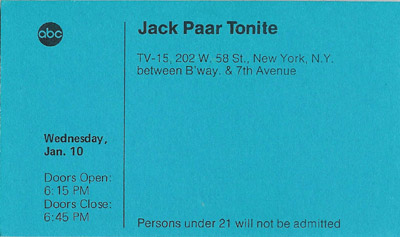

In 1973, ABC was enjoying some ratings success in prime-time and the execs there became infatuated with the idea that they could also win in late night. They began monkeying with the 11:30 slot, moving Cavett into a rotating format that performed worse than what it replaced. The other main component of this round-robin was Jack Paar Tonite, which failed and took Cavett’s show with it, which was our loss. Cavett went on to other, similar shows in other venues.

The above ticket says the show was done from something called TV-15. It was one of those theaters in New York that changed names and functions from year to year. It started life as the John Golden Theater in 1926 and was the Elysee the last time it housed plays. Dozens of different TV shows (including one of Merv Griffin’s) were done there in the fifties and sixties. Not long after Cavett vacated, it was turned into a church (which it had been occasionally before) and it was finally demolished in 1985.

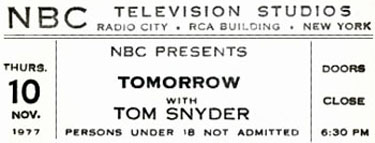

Tomorrow

In 1973, looking to expand revenues, NBC decided to stop signing off after Johnny Carson was over at 1 AM. Into the 1:00-2:00 AM time slot, they introduced Tomorrow, an interview show hosted by veteran newsman Tom Snyder. At the time, Snyder was the anchor of the local evening news program at the NBC affiliate in Los Angeles and garnering attention for his work there. (He was the last “single” anchorman in a major market. After him, it was all what the trade calls “boy-girl teams.”)

Tomorrow, at least in its first version, was a simple, low-budget interview show that often managed extraordinary guest bookings. People remember the nights that Snyder quizzed a John Lennon or a Charles Manson, but the guest list was always interesting…and if it wasn’t, the host had a way of making it interesting. When the guests were headline makers, there were occasional jurisdictional disputes within the network. During the Watergate controversy, several prominent figures would agree to be quizzed by Snyder, and NBC’s news division would object, insisting that protocol demanded that the interviewee appear instead with John Chancellor, who was then NBC’s main anchor. At least one or two “hot” guests managed to not appear at all while such disputes were being thrashed out.

But it wasn’t just the guests. Snyder opened each Tomorrow by chatting about whatever was on his mind, often displaying uncommon candor about what was going on in his life or on the network. These segments, along with his distinctive interviewing style, were often lampooned, especially on Saturday Night Live where Dan Aykroyd parodied Snyder with such precision (and frequency) that some observers felt it moved beyond satire and into animosity. Snyder would later complain, with some justification, that NBC execs who didn’t watch his show came to assume it had all the flaws and excesses of the Aykroyd spoof.

Tomorrow, which ping-ponged between Los Angeles and New York over its run, was usually done without a live audience but from time to time, when the guests were entertainers, that would change. (During the years the program was based in Burbank, it usually inhabited Studio 1, taping after Carson and his crew had left for the night.)

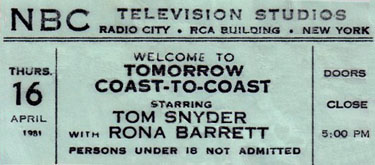

For years, it was a happy combo: 90 minutes of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, followed by 60 minutes of Tomorrow. Then in 1980, Mr. Carson decided to shave his show by one-third. At the time, an hour and a half was the standard length of a talk show and Johnny’s seemed unsatisfyingly short at first. But 60 minutes would come to seem natural for The Tonight Show and it’s now the standard length for all such programs. The only downside of Johnny’s decision turned out to be what happened to Tom Snyder’s program. NBC briefly discussed coming up with a new 30-minute comedy news show to fill the gap but finally decided to merely expand Tomorrow.

That might have been smart had someone also not decided that it needed to become more of an entertainment show with music and a studio audience, plus a co-host in the person of Rona Barrett. The gossip columnist could not have been a worse choice: She was an awkward, boring interviewer and she did her segments from Hollywood without a studio audience, thereby making her utterly disconnected from the main show Snyder was hosting in New York. Another problem was that Ms. Barrett always insisted that any TV camera only show her face from one specific angle. That hadn’t been a problem when her on-screen career had merely been a series of one minute gossip reports on other shows but a longer segment with her was like staring at a still photo.

She was eventually removed from the proceedings but by that point, it was too late: America had learned to go to bed when Johnny signed off. The Snyder part of the programming wasn’t bad, though ol’ Tom was clearly uncomfy in a format more suited to a stand-up comedian than a newsman. Eventually, it all went away and David Letterman came along. That was in 1982. Thirteen years later, after Letterman had moved to CBS, he brought Snyder back to do the show after him — a show nearly identical to The Tomorrow Show in its original format…the one they shouldn’t have tampered with in the first place. Snyder helmed The Late, Late Show until 1999.

(Thanks to Roy Currlin for one of the above tickets.)

Jack Paar Tonite

In the early seventies, ABC was getting respectable but not overwhelming ratings in late night with The Dick Cavett Show. Some at the network wanted to cancel Cavett and try something else but there was a problem: The show was critically-acclaimed at a time when very little on the ABC schedule was. No one wanted to endure the newspaper editorials and denouncements that would surely come if the network cancelled one of its few respected programs. The answer? The ABC Wide World of Entertainment, a rotating “wheel” of experimental and not-so-experimental programming in what had been Cavett’s time slot. One week a month, it would still be Cavett’s…so it wasn’t like ABC was dumping him; just cutting him back. Two weeks a month, it would be specials, some of which would be pilots for new programs. And the fourth week, it would be the second coming of Jack Paar…back hosting a late night show seven years after The Jack Paar Program (the prime time series he did after departing Tonight) left network television.

Paar’s new show debuted January 8, 1973 to surprisingly little notice. The first broadcast was a particular mess. At the taping, Paar was introduced by his announcer/sidekick Peggy Cass and the host entered to a thunderous ovation and proceeded to do a monologue that had the studio audience in hysterics, Then suddenly, his director (Hal Gurnee, who later gained fame directing David Letterman’s show) stopped the proceedings. There had been a technical snafu: No one had pressed the button to roll tape and they had to start over. Paar fumed, the audience had to pretend to laugh at jokes they’d heard only minutes before…and the show never quite recovered from that.

Later episodes with no technical glitches weren’t a lot better and people who’d heard of Paar but not seen him before got to wondering what was so special about the guy. He seemed out of touch with the current world, dragging out way too many anecdotes about the past. They brought on many of his old guests but the conversations seemed forced and not as wonderful as before. As the whole ABC Wide World of Entertainment tanked, Paar tanked with it. He later claimed that ABC had decided the rotating format wasn’t working and had pressed him to do the show every week instead of every fourth week. This seems unlikely since he was the lowest rated thing in the entire package. (Cavett’s ratings dropped, as well. Audiences just couldn’t get in the habit of following a show that disappeared from the air for weeks at a time. At one point, the legendary comedy writer Jack Douglas, who Paar had engaged to mail in monologue material, sent nothing for a long time until a note arrived. It said, “Sorry I didn’t send anything last week. I forgot you were on.”)

The show went largely unnoticed. On one episode, a young comedian named Freddie Prinze made his TV debut with a solid stand-up comedy routine…but nothing happened to his career. Later that year, Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show booked Prinze, he did just as well there…and became an overnight superstar with offers to headline in Vegas and star in his own TV pilot. Thereafter, Prinze just forgot about Jack Paar Tonite and referred to his appearance with Johnny as his TV debut. No one seemed to notice it wasn’t.

Jack Paar Tonite lasted eleven months before Paar resumed his retirement. He later appeared in occasional specials for NBC and PBS but had the good sense to not attempt another series, despite the occasional offer.

Tonight Show, The (1962)

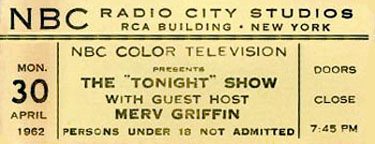

Jack Paar hosted his final episode of Tonight on March 30, 1962. Johnny Carson had been signed to replace him but Johnny was still under contract to host Who Do You Trust on ABC and wouldn’t be free until later that year. So for six months, guest hosts helmed the late night show, starting with Art Linkletter. Among others who took a week or two were Soupy Sales, Jerry Lewis, Joey Bishop, Steve Lawrence, Groucho Marx, Arlene Francis, Mort Sahl, Jack E. Leonard, Hal March, Donald O’Connor and even Paar’s old sidekick, Hugh Downs, who stayed on as announcer for the transition period and hosted at least one week. The above ticket is from one of several weeks hosted by Merv Griffin. NBC had him signed to do The Merv Griffin Show in the afternoons, just to keep him around in case Johnny bombed.

The six months of temps are truly lost episodes. There are no known videotapes or kinescopes, and pretty much everyone has forgotten about the period. My fuzzy memory — I was ten at the time — was that some of the hosts did a pretty good job, perhaps auditioning just in case Johnny didn’t work out. Others figured they had nothing to lose and turned the show into one long commercial for their other endeavors. Reportedly, Carson watched a few broadcasts in the latter category and called NBC to complain that they were destroying the show he was going to be taking over. Dick Cavett, who had previously been a Talent Coordinator for Paar, was on the writing staff.

One other note: Although it was casually referred to as The Tonight Show, it was not called that until Paar left. The Steve Allen version was called Tonight, as was the Paar version for his first few years, after which it became Jack Paar Tonight and then The Jack Paar Show. But Tonight and The Tonight Show were used informally throughout those years. Some TV listings still called it Tonight long after it was The Jack Paar Show on the air. So if one wanted to split follicles, one could say that the first host of The Tonight Show was Art Linkletter.

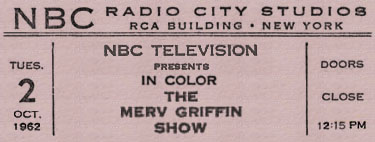

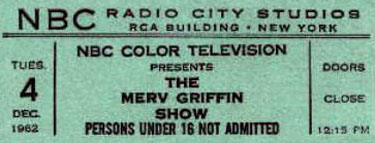

Merv Griffin Show, The (1962-1963)

In 1962 when Jack Paar decided to leave Tonight, several names were mentioned as possible replacements. Among them was a former band singer named Merv Griffin, who had recently been hosting the game shows Play Your Hunch for NBC and Keep Talking for CBS. He had also guest-hosted successfully for Paar and probably would have gotten the late night show, had NBC not opted to go with Johnny Carson. But just in case Johnny didn’t work out, NBC also signed Griffin and kept him in the bullpen. Merv hosted Tonight during the interim period after Paar departed but before Carson arrived. And then Merv started an afternoon talk show that debuted October 1, 1962 — the same day Johnny took over The Tonight Show.

As things turned out, Carson’s talk show succeeded but Merv’s did not. It was cancelled in less than a year. But Merv didn’t hurt for the experience. His deal with NBC had guaranteed that his production company could do a couple of game shows for the network. In short order, he was back on the air with Word for Word.