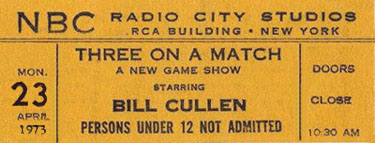

Three on a Match

A little less than two years after Eye Guess was cancelled, its producer (Bob Stewart) and host (Bill Cullen) and much of the same staff were back on NBC with Three on a Match. This one debuted in August of ’71 and lasted until June of ’74.

What was it about? That’s hard to say. It was even hard to say when it was on because the rules were complex and they kept changing. Basically, three players competed. They were shown a list of categories and they’d pick one and wager on how many true-false questions they thought they could answer in that category. With the cash they’d win by doing that, they’d buy squares on a big game board where pictures of prizes were hidden. If they revealed three matching prize pictures, they’d win that prize. Or at least, that’s how it went for a while. This was a confusing game and its producers were forever altering the rules to make it into smooth-running, simple affair.

They never quite managed that and at some point, it was apparently decided that it was easier to just chuck the whole thing and start over. So the last episode of Three on a Match aired on Friday, June 28, 1974. The following Monday, the exact same staff — including producer Stewart and star Cullen — were doing a new game show called Winning Streak in the same time slot on NBC.

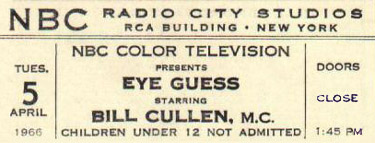

Eye Guess

Eye Guess was the first independent production of Bob Stewart, a game show producer who’d previously worked for Goodson-Todman Productions where he’d supervised and/or developed hits including To Tell the Truth, Password and the original The Price is Right. On the last of these, which had just been cancelled after its long run, Stewart worked with emcee Bill Cullen, and when Stewart struck out on his own, he tapped Cullen to host his first show.

On Eye Guess, two players confronted a game board containing nine squares like a tic-tac-toe game. In round one, they’d be shown eight possible answers to upcoming questions…but only for eight seconds. Then as Cullen asked questions, they’d call out numbers — i.e., “The answer to that one is behind Number Six, Bill!” Sometimes, the correct answer was none of the eight and if they thought that, they’d select the middle square, which was the “Eye Guess” space. If you racked up enough correct guesses, you won. Simple as that.

Eye Guess was a modest hit, lasting on NBC from January of ’66 to September of ’69. Cullen was not idle for long. The same month Eye Guess went off, Goodson-Todman revived To Tell the Truth as a daytime show and included him on its panel. Two years later, he was also back as a host…on a new NBC game show, Three on a Match, also produced by Bob Stewart.

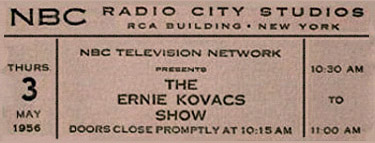

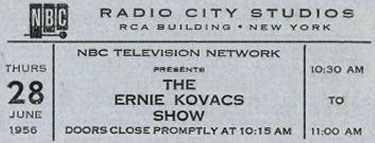

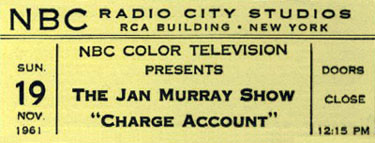

Ernie Kovacs Show, The (1955-1956)

Ernie Kovacs spent much of the fifties wandering from network to network and show to show, doing essentially the same program. The critics loved him and his innovative brand of comedy. Audiences liked him but not enough to make any one show enough of a hit that he stayed in one gig for very long.

Today, when you see clips of his work, the emphasis is on silent bits that pushed the envelope of what was technically possible in television at that time. I always thought those compilations, though impressive, missed the point of Kovacs. First of all, a lot of the visual stuff was his wholly the work of his writers. (Kovacs isn’t even in some of the most-seen excerpts.) Secondly, some of them are merely a matter of replicating in a TV studio bits that had previously been done on film by Buster Keaton or Harold Lloyd or even — in the case of one clip in particular — The Three Stooges. That’s the one where he’s sitting on a tree branch, sawing off the branch he’s sitting on…and the tree falls while the branch remains in the air.

The clips that suggest Kovacs was worthy of his exalted reputation are the ones where he talks…as one of his characters (like the effeminate poet, Percy Dovetonsils) or even as Ernie Kovacs. He was a very funny man without the gimmicked props and the trick photography.

No one ever seems to have compiled a definitive list of all the shows that Kovacs starred in over the years. Some did not last long and there were even times when he was doing two shows at the same time. Most articles about him, for instance, will tell you of an hour-long prime-time series he did on Monday nights for NBC from December of 1955, lasting until the following September. It was called The Ernie Kovacs Show but the above tickets are from a rarely-mentioned half hour daily morning show with the same name that he was doing during the same period. At some point in there, he stopped doing the morning show and was filling in for Steve Allen on Tonight.

Later on, there were other shows…on and off, here and there, until his death in a car crash in 1962. It robbed TV viewers of one of the funniest human beings they ever got to follow from show to show.

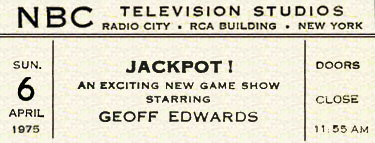

Jackpot!

Jackpot! was an extremely new game show that went on NBC in 1974…a show that was supposed to usher in a new era in daytime television. Although the series itself did not succeed, a number of its innovations did become somewhat standard in the world of game shows. One was to go for a more “open” look. Instead of a set that enclosed the action in three cramped walls, the stage was wide open with a less claustrophobic feel. The other change was to go for a younger, sexier host…someone who might appeal to housewives in a way that most of the usual hosts did not.

That host, hand-selected by NBC exec Lin Bolen, was Geoff Edwards. She rejected dozens of candidates in New York (where Jackpot! would be taped) and instead, Edwards would be flown in most weekends from Los Angeles where he did a Monday-Friday radio show on station KMPC. She also reportedly supervised a new hairstyle for Edwards, as well as a whole new wardrobe that consisted mostly of the then-popular leisure suits.

Jackpot! was about riddles. Sixteen contestants would compete for a week at a time and at any given time, one would be designated as King of the Hill (or Queen, as applicable). When you were King/Queen, the others would read you the riddles and as long as you kept answering correctly, you’d continue playing and the jackpot would continue building. When you happened on the Jackpot Riddle!, a correct answer would cause the pot to be divided between you and the person who’d asked you the riddle.

Jackpot! replaced The Who, What or Where Game on the NBC schedule but not in the same time slot. Jeopardy!, which was then NBC’s most popular daytime program, was relocated there and the Jeopardy! time slot went to the new program. As explained on our page for the displaced show, its producer — Merv Griffin — was unhappy to see his series bumped to a new time so that Bolen could give every possible chance to Jackpot!, which was one of the first shows she supervised at the network. And then Bolen was unhappy that Jackpot! failed to click with viewers. It got consistently lower ratings than Jeopardy! and went off the air in September of 1975. (Some credited the failure with costing NBC its dominance in daytime. Jeopardy! was also cancelled and thereafter, soap operas on CBS and ABC ruled the morning hours.)

But Jackpot! had two afterlives, both with essentially the same format and set. A 1985 version was produced in Canada, primarily for airing on the USA Network in this country. It was hosted by Mike Darrow and lasted until 1989. Shortly after, a third version was produced for syndication in Southern California with Edwards returning to the host position. This one went unseen in many cities and failed after one year when its distributor collapsed. All of these were produced by Bob Stewart Productions, which had better luck with different incarnations of The $10,000 Pyramid.

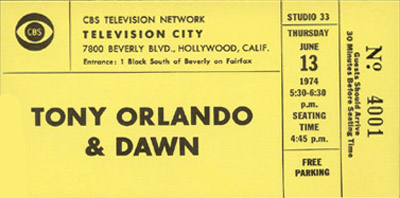

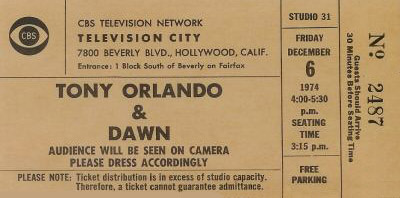

Tony Orlando & Dawn

Before he “made it,” Tony Orlando drifted back and forth between working behind the scenes in the record business and in front of the microphone. Once he and two back-up singers scored big with “Candida,” “Knock Three Times” and “Tie a Yellow Ribbon ‘Round the Ole Oak Tree,” TV execs came calling, hoping the replicate the success of Sonny and Cher in a variety format. Orlando and the two ladies who comprised Dawn (Telma Hopkins and Joyce Vincent Wilson) didn’t quite have the same knack for snappy and mutually-insulting banter but their show had enough music and enough energy, as well as a stellar array of guests. It debuted as a summer series in 1974 and managed to stick around until December of ’76. For its last gasp, it was renamed The Tony Orlando and Dawn Rainbow Hour, as a way of signalling that it was undergoing some kind of unspecified revamp. The new title doesn’t seem to have meant much difference to anyone.

The reference on one of the above tickets to the audience being seen on camera refers to a weekly segment in which Orlando would wade out into the crowd, perform in the aisles and sometimes get audience members up to sing and dance with him. It became a signature routine of his and one that sparked battles amidst the show’s production staff and at the network, some of whom felt it was amateurish. The live audience loved it (no surprise) and each week, the producers would way overtape such material, then quarrel in the editing room over how much to include. There’d be pointed arguments that every song that Tony performed with a fat lady in an aisle seat meant they’d have to cut out a polished, rehearsed musical spot with one of the show’s well-paid and professional guest stars. On the other hand, even those who fought for less audience numbers had to admit that Tony was never better than when he and his fans were energizing one another. He had a genuine love for the people who came to see his shows tape (and vice-versa) and that probably is what is best remembered from that series.

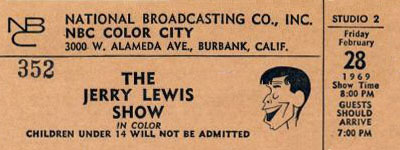

Jerry Lewis Show, The (1967-1969)

Jerry Lewis has had a checkered career on television. He and Dean Martin scored big on The Colgate Comedy Hour (1950-1955) where they were among the show’s rotating hosts. A series of specials did well but then in 1963, he attempted a two-hour live variety/talk show for ABC that was one of television’s most spectacular disasters. It was supposed to be a two-year “firm” committment but after dismal ratings and killer reviews, Lewis announced he was too busy with his film career to do television and exited after thirteen weeks.

Four years later, that film career was starting to fade and he reappeared on NBC with a more conventional variety series done, unlike his earlier efforts which were all live, on tape. It debuted on September 19, 1967 to indifferent response and disappointing ratings. (Lewis was said to have been unamused by the unidentified person who, the day before his debut, papered the NBC studios and Lewis’s car with signs that said, “Ban the bomb before it goes off.”) But NBC believed that Jerry might catch on, as his former partner had with The Dean Martin Show, and kept the fesitivities going for two years. The final broadcast was May 27, 1969.

It was not a great show. Jerry seemed to have trouble relating to any guest or topic that couldn’t have been on the old Colgate Comedy Hour. Many of the guests and jokes actually did date back that far. The sketches were weak and much of the show was devoted to Jerry’s questionable singing talents. Some people seem to recall that during this period, he and Dean exchanged cameo guest appearances but that never happened. Dean did, however, take time on his show to ask people to watch Jerry’s first episode.

Jerry Lewis never had another TV series after that…unless you count his annual Labor Day telethon to benefit Muscular Dystrophy. In 1984, he starred in a week of pilot episodes for a talk show. Thought he trotted out heavyweight guest stars — including Frank Sinatra on the opener — the show didn’t click. Reviewers faulted it (rightly) for devoting way too much of its air time to the host, the guests and sidekick Charlie Callas all discussing the greatness of each other. Since then, Jer has been a frequent guest star on other shows, slowly ascending to Legend status. My favorite of all his appearances was one night when he was on with David Letterman and Dave asked him, as a personal favor, just to run around the stage and act crazy. Jerry was a bit puzzled but he obliged.

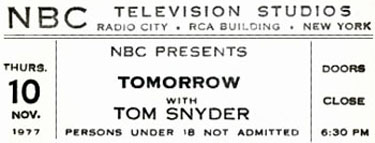

Tomorrow

In 1973, looking to expand revenues, NBC decided to stop signing off after Johnny Carson was over at 1 AM. Into the 1:00-2:00 AM time slot, they introduced Tomorrow, an interview show hosted by veteran newsman Tom Snyder. At the time, Snyder was the anchor of the local evening news program at the NBC affiliate in Los Angeles and garnering attention for his work there. (He was the last “single” anchorman in a major market. After him, it was all what the trade calls “boy-girl teams.”)

Tomorrow, at least in its first version, was a simple, low-budget interview show that often managed extraordinary guest bookings. People remember the nights that Snyder quizzed a John Lennon or a Charles Manson, but the guest list was always interesting…and if it wasn’t, the host had a way of making it interesting. When the guests were headline makers, there were occasional jurisdictional disputes within the network. During the Watergate controversy, several prominent figures would agree to be quizzed by Snyder, and NBC’s news division would object, insisting that protocol demanded that the interviewee appear instead with John Chancellor, who was then NBC’s main anchor. At least one or two “hot” guests managed to not appear at all while such disputes were being thrashed out.

But it wasn’t just the guests. Snyder opened each Tomorrow by chatting about whatever was on his mind, often displaying uncommon candor about what was going on in his life or on the network. These segments, along with his distinctive interviewing style, were often lampooned, especially on Saturday Night Live where Dan Aykroyd parodied Snyder with such precision (and frequency) that some observers felt it moved beyond satire and into animosity. Snyder would later complain, with some justification, that NBC execs who didn’t watch his show came to assume it had all the flaws and excesses of the Aykroyd spoof.

Tomorrow, which ping-ponged between Los Angeles and New York over its run, was usually done without a live audience but from time to time, when the guests were entertainers, that would change. (During the years the program was based in Burbank, it usually inhabited Studio 1, taping after Carson and his crew had left for the night.)

For years, it was a happy combo: 90 minutes of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, followed by 60 minutes of Tomorrow. Then in 1980, Mr. Carson decided to shave his show by one-third. At the time, an hour and a half was the standard length of a talk show and Johnny’s seemed unsatisfyingly short at first. But 60 minutes would come to seem natural for The Tonight Show and it’s now the standard length for all such programs. The only downside of Johnny’s decision turned out to be what happened to Tom Snyder’s program. NBC briefly discussed coming up with a new 30-minute comedy news show to fill the gap but finally decided to merely expand Tomorrow.

That might have been smart had someone also not decided that it needed to become more of an entertainment show with music and a studio audience, plus a co-host in the person of Rona Barrett. The gossip columnist could not have been a worse choice: She was an awkward, boring interviewer and she did her segments from Hollywood without a studio audience, thereby making her utterly disconnected from the main show Snyder was hosting in New York. Another problem was that Ms. Barrett always insisted that any TV camera only show her face from one specific angle. That hadn’t been a problem when her on-screen career had merely been a series of one minute gossip reports on other shows but a longer segment with her was like staring at a still photo.

She was eventually removed from the proceedings but by that point, it was too late: America had learned to go to bed when Johnny signed off. The Snyder part of the programming wasn’t bad, though ol’ Tom was clearly uncomfy in a format more suited to a stand-up comedian than a newsman. Eventually, it all went away and David Letterman came along. That was in 1982. Thirteen years later, after Letterman had moved to CBS, he brought Snyder back to do the show after him — a show nearly identical to The Tomorrow Show in its original format…the one they shouldn’t have tampered with in the first place. Snyder helmed The Late, Late Show until 1999.

(Thanks to Roy Currlin for one of the above tickets.)

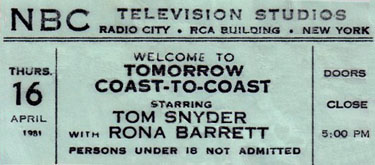

Jan Murray Show, The

What we have here is a game show where nobody particularly liked the game. When NBC cancelled Treasure Hunt, it was with the express intention of finding a better vehicle for its host, Jan Murray. He was back in a matter of weeks — as of September 5, 1960 — with Charge Account, a weak game with a good host. So as the months went on, the program became less about winning money and more about Murray chatting with the contestants. In mid-run, it was renamed The Jan Murray Show and by that point, it was at least as much talk show as game. There’d be a fun conversation and then at some point, it would come to a halt and Murray would say, with as much enthusiasm as he could muster, “Well, I guess it’s time for you to win some money.” It was not unlike the way Groucho Marx on You Bet Your Life sometimes treated the quiz part of the show as an intrusion on the entertainment.

Maybe it wouldn’t have been like that if the game itself had been better. Murray would take tiles, each of which had a letter on it, and mix them up in a drum. Then he’d pull them out as if calling Bingo and read the letters off. The contestants had Bingo-style cards in front of them and they’d attempt to form words as they wrote the letters onto their cards. After that, an English professor-type gentleman would grade their cards, awarding them so many points for each three-letter word, so many for each four-letter word and so on. Pretty boring stuff.

All the databases say that it was a half-hour show but I seem to recall either that it ran an hour for at least one week, or that some article said it was going to go to an hour. I also have the vague memory of them dumping the game completely the last few weeks and trying to keep it going as a straight talk show, which is probably what it should have been in the first place.

The “home game” of Charge Account was apparently manufactured to excess: It was well-represented in every toy store and after the show was cancelled, it was possible to buy it, at least in the stores around me, for practically nothing. Which was about what it was worth. Since it didn’t come with the one good thing about the TV show — Jan Murray’s banter — there was no reason to even open the box.

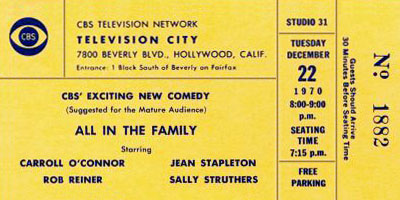

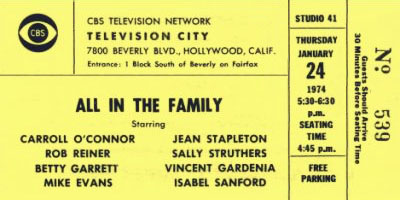

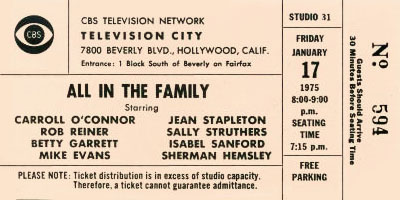

All in the Family

One of television’s most ground-breaking TV shows, All in the Family, debuted on CBS on January 12, 1971…so folks who used the top ticket above to attend a taping had no idea what to expect. The show had been developed for ABC and its pilot was taped twice, both times with Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton in the leads, though with other actors playing the kids each time. When CBS bought the third version of the pilot, the network was in a transition period, dumping shows that skewed older and/or to rural audiences. They were trying to reposition the network for younger, more urban viewers and Norman Lear’s new series was a daring step in that direction.

The show was not an immediate hit. When its early airings were noticed at all, it was to discuss the coarse, bigoted language employed by its central character, Archie Bunker. But CBS stuck with it and audiences discovered it about the time the first thirteen episodes were in rerun. When it was moved from Tuesday nights at 9:30 to Saturday nights at 8:00, it became not only a smash hit but the leader of a new wave of television comedy.

I attended a taping of All in the Family in 1972. What I recall most about the evening was that the warm-up, done by Norman Lear himself, was very long and he kept (a) plucking ladies out of the audience and dancing the tango with them in the aisles, and (b) urging us to watch his new series, Maude. The episode itself had Vincent Gardenia and Rue McClanahan playing a couple that had placed an ad for wife-swapping, and Edith Bunker innocently answered it. Soon after, Gardenia came back as a semi-regular, along with Betty Garrett, while Ms. McClanahan went over to Maude. Before long, there would be other spin-offs, like The Jeffersons, starring Isabel Sanford, Sherman Hemsley and Mike Evans, whose names can be seen on some of the above tickets.

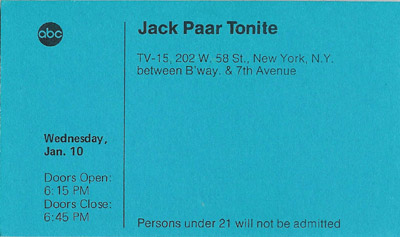

Jack Paar Tonite

In the early seventies, ABC was getting respectable but not overwhelming ratings in late night with The Dick Cavett Show. Some at the network wanted to cancel Cavett and try something else but there was a problem: The show was critically-acclaimed at a time when very little on the ABC schedule was. No one wanted to endure the newspaper editorials and denouncements that would surely come if the network cancelled one of its few respected programs. The answer? The ABC Wide World of Entertainment, a rotating “wheel” of experimental and not-so-experimental programming in what had been Cavett’s time slot. One week a month, it would still be Cavett’s…so it wasn’t like ABC was dumping him; just cutting him back. Two weeks a month, it would be specials, some of which would be pilots for new programs. And the fourth week, it would be the second coming of Jack Paar…back hosting a late night show seven years after The Jack Paar Program (the prime time series he did after departing Tonight) left network television.

Paar’s new show debuted January 8, 1973 to surprisingly little notice. The first broadcast was a particular mess. At the taping, Paar was introduced by his announcer/sidekick Peggy Cass and the host entered to a thunderous ovation and proceeded to do a monologue that had the studio audience in hysterics, Then suddenly, his director (Hal Gurnee, who later gained fame directing David Letterman’s show) stopped the proceedings. There had been a technical snafu: No one had pressed the button to roll tape and they had to start over. Paar fumed, the audience had to pretend to laugh at jokes they’d heard only minutes before…and the show never quite recovered from that.

Later episodes with no technical glitches weren’t a lot better and people who’d heard of Paar but not seen him before got to wondering what was so special about the guy. He seemed out of touch with the current world, dragging out way too many anecdotes about the past. They brought on many of his old guests but the conversations seemed forced and not as wonderful as before. As the whole ABC Wide World of Entertainment tanked, Paar tanked with it. He later claimed that ABC had decided the rotating format wasn’t working and had pressed him to do the show every week instead of every fourth week. This seems unlikely since he was the lowest rated thing in the entire package. (Cavett’s ratings dropped, as well. Audiences just couldn’t get in the habit of following a show that disappeared from the air for weeks at a time. At one point, the legendary comedy writer Jack Douglas, who Paar had engaged to mail in monologue material, sent nothing for a long time until a note arrived. It said, “Sorry I didn’t send anything last week. I forgot you were on.”)

The show went largely unnoticed. On one episode, a young comedian named Freddie Prinze made his TV debut with a solid stand-up comedy routine…but nothing happened to his career. Later that year, Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show booked Prinze, he did just as well there…and became an overnight superstar with offers to headline in Vegas and star in his own TV pilot. Thereafter, Prinze just forgot about Jack Paar Tonite and referred to his appearance with Johnny as his TV debut. No one seemed to notice it wasn’t.

Jack Paar Tonite lasted eleven months before Paar resumed his retirement. He later appeared in occasional specials for NBC and PBS but had the good sense to not attempt another series, despite the occasional offer.