Joey Bishop Show, The (1967-1969)

For decades, ABC and CBS tried over and over to establish a berth in late night television and to compete successfully with Johnny Carson on NBC. In 1967, after giving up on a news-oriented discussion program called The Les Crane Show, ABC dropped Joey Bishop into the time slot with a 90 minute talk show that was pure, Tonight Show-style entertainment. Bishop was a natural choice: He’d served well as a guest host for Carson and for Jack Paar before him. And the public seemed to like him. They’d watched the previous Joey Bishop Show — a situation comedy — in sufficient number to keep it on the air from 1961 to 1965. On it, Bishop played a talk show host so, in yet another case of life imitating art, he became a real talk show host.

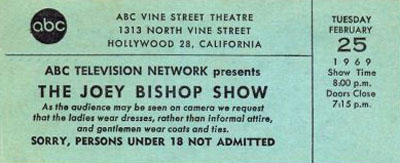

Bishop’s new show had many things going for it. Regis Philbin was a fine announcer and sidekick who sometimes managed to steal the spotlight from his boss. Johnny Mann was the bandleader and he gave the show a good sound. The whole thing emanated from Hollywood at a time when Carson was still based in New York. That — and Bishop’s many show biz friendships — seemed to guarantee a steady stream of big name guests, though operating on the West Coast did have one big disadvantage. As you can see from the ticket, The Joey Bishop Show taped in the evening. That meant a one-day delay in being broadcast. With so much in the news, Carson’s monologues and guest chats were becoming more topical and Bishop was lagging a day behind. If as sometimes happens in comedy writing, the same joke occurred to both writing staffs at the same time, Joey would be uttering it twenty-four hours after America had heard it from Johnny.

In fact, the biggest plus Bishop had when his show debuted on April 17, 1967 was that he wasn’t opposite Johnny Carson, who was then engaged in a battle with NBC over compensation and control. Johnny was off the air for several weeks, leaving The Tonight Show to a series of guest hosts — primarily country-western singer Jimmy Dean — and the late night audience to Joey. For a brief time, it looked like ABC was establishing its foothold in the time slot and that may have stampeded NBC into acceding to Carson’s demands, which they did. When Johnny returned to his natural habitat, Joey’s ratings dropped significantly. Thereafter, he trailed and the gap grew slowly wider…not that there weren’t moments when it looked like Joey was clawing his way back. Johnny took a lot of vacations, and they always gave Joey a little bump. And when his numbers dipped and rumors of cancellation began to swirl, Joey could usually manage to land a superstar guest and bring some audience back.

One of his highest ratings came after a taping when Regis Philbin abruptly announced that he was quitting the show. The one day delay worked to the show’s benefit that time. The news spread and much of America tuned in to hear Philbin announce — apparently stunning Joey — that the network had never wanted him in the first place and that he had endured too much criticism from them that he was dragging down the show. A few nights later, everyone watched again to hear Bishop announce that everything had been smoothed over, after which he welcomed Regis back to the show. The incident gave Joey two of the few nights he beat Carson but several TV critics suggested it was all an arranged stunt.

Finally though, ABC had to accept the reality of atrophying ratings. In late ’68, CBS announced that Merv Griffin would host an 11:30 talk show to commence the following March. Recognizing that this would split the already-small audience of folks who didn’t choose to watch Johnny, ABC decided to see if Dick Cavett could succeed where Bishop hadn’t. Sure enough, when Merv went on, Joey’s numbers plunged. Bishop didn’t even host the final weeks of his program, leaving it to guest hosts until it was replaced by Cavett in May. Not long after, Carson enlisted Joey as his main guest host and Joey wound up sitting behind Johnny’s desk 177 times, which was the house record until 1983 when Joan Rivers was named “permanent guest host.” It was a great example of the old show business maxim” “If you can’t beat ’em, fill in for ’em.”

Tonight (1957-1962)

Steve Allen hosted his final episode of Tonight on January 25, 1957. The following Monday, NBC debuted a new multi-hosted, “magazine” show in the time slot…Tonight: America After Dark. It was an instant flop and they hurriedly began searching for someone who could do a new version of Tonight more like the old version. The logical choice might have been Ernie Kovacs, who’d hosted two nights a week during the final months of Allen’s run…but Kovacs was off in Hollywood appearing in movies and therefore unavailable. Instead, they picked Jack Paar, who had hosted a dizzying array of short-lived programs for all the networks in the preceding years. He took over NBC’s late night time slot on July 29, 1957.

The early Paar Tonight program was a mess. At one point before its debut, someone at NBC got the brilliant idea that it should consist of three separate game shows. Each night, the contestant who won the first would move on to appear on the second…and so forth. This notion was discarded, in part because America After Dark was sinking fast and there wasn’t the time to develop three new game shows. So they went with the idea of conversation/chat show but even then, NBC wanted to save a tiny amount of money by booking guests a week at a time — the same people for five nights in a row. This too was discarded but for the initial weeks, Paar struggled to make conversation with eccentric guests in whom he had no interest. Further souring the proceedings was the man selected as Paar’s sidekick, veteran comic actor Franklin Pangborn. Pangborn had been funny in scripted film parts but on a live, ad-lib show he was a disaster.

For several months, Paar teetered on the brink of cancellation but then everything miraculously came together. Pangborn was eliminated and eventually, the show’s announcer — Hugh Downs — expanded his role to full sidekick status. And Paar found his style and the right kind of guest to have on. He soon had a whole stock company of recurring visitors that included Alexander King, Oscar Levant, Dody Goodman, Jonathan Winters, Peter Ustinov, Hans Conried, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Elsa Maxwell, Cliff “Charlie Weaver” Arquette and Peggy Cass.

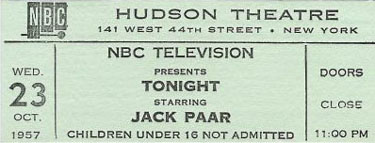

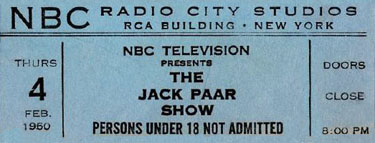

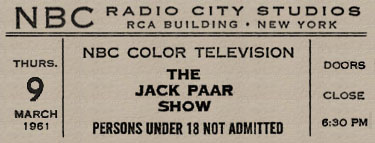

In these tickets, one can see things changing. Paar didn’t like staying up late — he once said he’d never watch his show if he hadn’t been on it — so when taping became more practical, it went from a live show to one recorded earlier and earlier in the evening. For some reason, as they moved it earlier, they decided to raise the minimum audience age from 16 to 18.

But the big change was in the name. Few recall that there were a few years there when Tonight ceased to exist and it became just The Jack Paar Show, though many people, Paar included, continued to refer to it as “The Tonight Show,” which technically had not yet been its name. It was just Tonight. As you can see from the above ticket for 2/4/60, it was The Jack Paar Show then. Exactly one week later — 2/11 — Paar did his famous on-air resignation because the network had censored an innocuous joke about a “water closet” and what he said when he quit for several weeks was, “I’m leaving The Tonight Show.” Before that, there had also been a brief interim period when its title had been Jack Paar Tonight. (Paar’s unsuccessful attempt to return to the format in 1973 would be called Jack Paar Tonite.) In Paar’s final months, NBC did all it could to get the word “Tonight” back into promotions and TV Guide and to pretend that that had been the name all along.

Paar did his final show in the time slot on March 30, 1962, and the show was handed over to guest hosts for six months to await the arrival of Johnny Carson. After a brief hiatus, he returned to NBC with a shorter but largely identical weekly prime time series called The Jack Paar Program that ran until 1965.

Tonight (1954-1957)

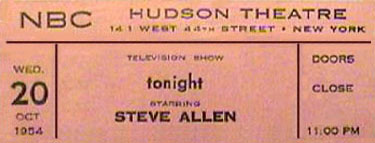

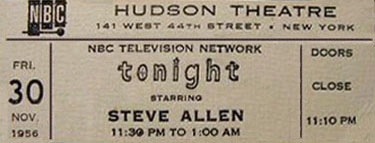

In 1954, NBC exec Sylvester “Pat” Weaver was looking for a show that could open up the late night time slot for network programming. He’d previously tried a raucous variety show there — Broadway Open House, hosted some nights by Morey Amsterdam and others by Jerry Lester. This time, his search led him to The Steve Allen Show, which the New York NBC station had recently begun airing. That show was acquired, retitled and expanded…and it debuted on September 27, 1954 as Tonight! Histories note that the exclamation point was soon deleted…and we can see there is none on the earliest ticket above, which is from October 20.

Tonight did everything it could to fill the time: There were games, interviews, sketches, songs…even, for a brief time, a nightly (real) news round-up. Steve played piano, chatted with eccentric guests and audience members and put up with stunts which he sometimes described as “plots by the staff against my life.” Gene Rayburn was the announcer and sidekick, Skitch Henderson led the band and the regulars included singers Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Pat Marshall and Andy Williams. Allen also developed a “stock company” of talented comedians like Don Knotts, Louis Nye, Tom Poston and Dayton Allen, though some of these didn’t join him until his post-Tonight ventures.

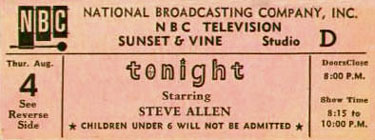

Most of the time, as the above tickets show, Tonight came from the Hudson Theater in New York. The one ticket above for a broadcast from the West Coast is for August 4, 1955. For eight weeks that year, Tonight emanated from Hollywood where Steve Allen was filming the title role in the movie, The Benny Goodman Story. Most performers would consider it a tiring full-time job to either host a late night show five evenings a week or to star in a major motion picture. Somehow, without missing a day on either, Allen managed to do both…though right after, he did take his first two-week vacation from Tonight, turning the festivities over to guest host Ernie Kovacs.

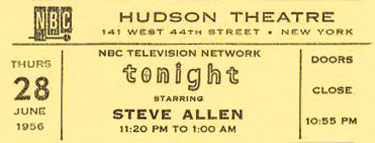

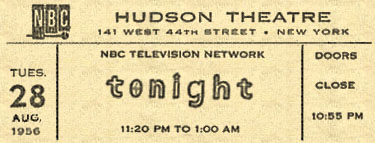

The August 28, 1956 ticket lacks the name of Steve Allen because it was for a Tuesday night. In June of that year, Allen and his crew had added a prime-time Sunday night series to their workload, competing on NBC against Ed Sullivan’s popular CBS program. The burden became too great and soon after, the Monday and Tuesday night broadcasts of Tonight were turned over to a roster of ever-changing guest hosts, including Ernie Kovacs, Jack Paar, Henry Morgan, Bill Cullen, Gene Rayburn, Rudy Vallee, Tony Randall, cartoonist Al Capp and even, from the old Broadway Open House, Morey Amsterdam and Jerry Lester. It is not known who was hosting on the eve of the above ticket, but Kovacs became the regular Monday-Tuesday host in October.

He continued, with Allen hosting the rest of the week, until the end of January, 1957 when Allen decided to give up the late night show. The entire thing was replaced by a famous disaster — a multi-hosted “magazine” show called Tonight: America After Dark. When that didn’t work, they went scurrying to find another single host who could do something more like what Steve Allen had done. The result was the Jack Paar era of Tonight.

The Steve Allen years remain legendary but largely lost: As with many shows of the day (including the Tonight run of Paar and the early years of his successor, Johnny Carson) few tapes or kinescopes exist. Allen went on to do more shows, some of which were in a similar enough format that many people remember them when they think they’re remembering his years on Tonight. This can get you to wondering if the lost shows are legendary in part because they are lost, and are appraised only through rose-colored memories. Judging from what does exist — and from those later shows — that’s not the case here. Steve Allen’s Tonight does seem to have been as unpredictable, spontaneous and innovative as everyone remembers…the kind of show you dared not miss because the next day, everyone would be saying, “Did you see what happened on that show last night?” Talk shows aren’t like that anymore. They don’t have anyone as brave and as willing to soar before millions without controls and preparation as was Steve Allen.

We do have a mystery with these tickets. Every single history of Tonight says that for its entire run, the Steve Allen version was an hour and 45 minutes in length, commencing at 11:15 PM in the East. Yet here, we see that the 6/28/56 and 8/28/56 tickets give an airtime of 11:20 PM to 1:00 AM, and the 11/30/56 ticket says 11:30 PM to 1:00 AM. If there’s an explanation for this, I’d love to hear it.

Steve Allen Show, The (1953-1954)

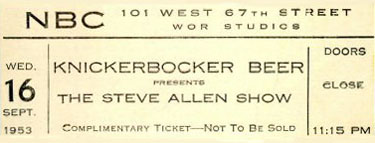

In 1953, the local NBC station in New York was WNBT and its late night movie program was getting clobbered by a better package of films being broadcast every night on the CBS affiliate, WCBS. Knickerbocker Beer, which was then a major brand, decided it wanted to sponsor something else on WNBT…say, a variety show. Ted Cott, a successful radio executive who had recently moved into television at the NBC affiliate, suggested Steve Allen as host.

Histories say that Allen debuted in the Fall of ’53 with a 45 (or 40 in some accounts) minute program every night called The Knickerbocker Beer Show, and that after thirteen weeks, its name was changed to The Steve Allen Show. The above ticket suggests that the name change came much more rapidly than that.

Done at first without writers and always without much of a budget, Allen’s local show was an immediate success, garnering both critical acclaim and the desired higher (than WCBS) ratings. On it, Allen would play the piano, chat with audience members or guests or sidekick-announcer Gene Rayburn, bring on Steve Lawrence and/or Eydie Gorme to sing a song — the bandleader was Bobby Byrne — and basically lay the foundation for talk shows to come. Less than a year later, most of the operation would be moving over to do a network show called Tonight.

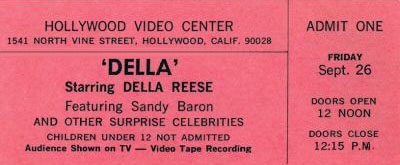

Della

In 1969, we had another one of those occasional periods when it seems like everyone with a S.A.G. card is getting to host a new talk show. Singer Della Reese’s was ballyhooed as the first one ever hosted by an Afro-American but it had more to recommend it than just that. She was a pretty good host and an awful lot of fine musical performers were enlisted to guest and to duet with Ms. Della. But actually, the best thing about the show was her co-host, comic Sandy Baron, who ably supplied whatever Reese couldn’t in the comedy department. They made a pretty good parlay and one of the industry trade papers later attributed the short run of Della to the fact that the field was then flooded with talk shows and there simply weren’t enough time slots for them all.

The best part of every episode was a segment at the end where Della, Sandy and that day’s guests would sit on stools and improvise short comedy scenes based on what were described as “suggestions from the audience.” Often in the world of improv comedy, that means that they had audience members write down some ideas which then went to someone who’d substitute pre-scripted premises…or maybe see if any of the audience submissions could be reworded slightly into one of the planned bits. I didn’t know much about improvisation in 1969 and since I recall those segments as being sometimes very funny, I wonder now if they were on the up-and-up. It’s certainly possible because Baron was the driving force in almost all of them and he was a very gifted comedian.

Baron was then on the rebound from the cancellation of Hey, Landlord!, a pretty funny sitcom he did for one season (1966-1967). A few years later, he would score a major success when he took over the role of Lenny Bruce in the Broadway play, Lenny. But failure was apparently more comfortable for Baron. It is said that the Lenny experience led to one of several mental breakdowns he was to suffer. Every time things were going well for him, friends observed, he’d go nuts, disappear and live as a homeless person for months. From time to time, he would surface again and often get some decent gig — Woody Allen hired him to be the on-camera narrator of most of Broadway Danny Rose — and then he’d crash-dive and submerge again. He developed chronic emphysema and the one time I met him, he was strapped to a portable oxygen tank. He was then living in a hotel thanks to some money he’d received as charity from acquaintances…but he was incapable of working and he said that when the funds ran out, he expected to go back out and live on friends’ couches and in the streets, oxygen tank and all. This was about two years before his death in 2001. I think acquaintances chipped in and kept him from sleeping in alleys for the rest of his life but still, it was a sad ending for someone who was once, albeit briefly, the hottest new comic in the business.

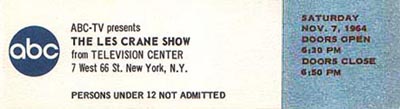

Les Crane Show, The

A radio host named Les Crane figured into ABC’s early attempts to get into the late night market. Crane’s show went for serious talk about issues in a cross between what Mike Wallace had done and what Phil Donahue would do, with much participation from a studio audience. They were seated in a kind of amphitheater formation around the stage, and if someone in the house had a question to ask or a point to make, they’d stand up and Crane would aim his “shotgun mike” at them — a microphone that actually looked like a shotgun — supposedly to pick up their voices. (Some critics suggested the device was more for theatrics than audio.)

It was a pretty good show, though sometimes a bit overly-dramatic. ABC gave up on Crane after four months, renamed the show Nightlife and tried an array of guest hosts, none of whom clicked. So they brought Crane back, added Nipsey Russell as co-host, and tried to do a more entertainment-oriented show, which did even less well. Eventually, Crane went back to radio, and The Joey Bishop Show got the time slot. The above ticket was for one of Crane’s very first shows and it displays one of the reasons his initial format didn’t work. This was a Monday-Friday show discussing what was going on in the world, right? So why were they taping it on Saturday evening? (Thanks to Brian Gari for the ticket.)