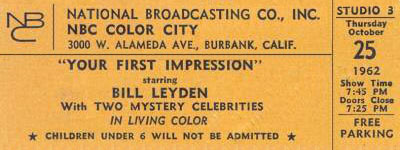

Your First Impression

Monty Hall sold his first game show as a producer to NBC in 1962. It went on the air in January of that year, more or less replacing It Could Be You, inherting the host of that show, Bill Leyden, and its producer, Stefan Hatos. Your First Impression was based on the semi-psychological exercise of asking people questions to which they’re expected to reply with the first thing that comes into their minds. A typical question might be to finish the sentence, “The thing I don’t do well is…” Or “If I could do any other job in the world, I’d be a…”

There were occasional variations in the format but the main game involved bringing on a mystery celebrity and asking him or her questions of that nature. A celebrity panel was given the name of five possible contenders and based on the responses, they had to figure out which of the five was present in the studio with them. Once, the mystery celeb was Richard Nixon, who was asked to complete the sentence, “I wish I’d been…” and who gave it away when he came back with “…the captain of a P.T. boat.”

Leyden was a cheery, laid-back gent who kept things moving nicely but who had health problems that caused him to miss the show from time to time. Monty Hall filled in occasionally and then Dennis James, who was often on the celebrity panel, took over as host for an extended period. The show went off the air in 1964, by which time Mr. Hall was quite busy. In the interim, he and Stefan Hatos had formed a production company together and sold a show called Let’s Make a Deal.

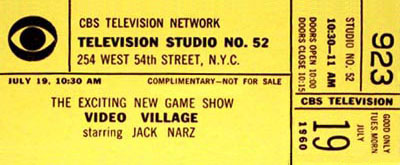

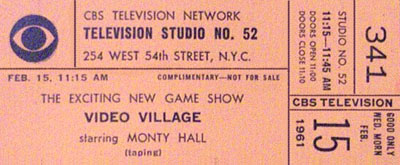

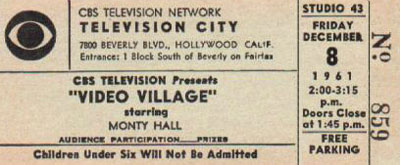

Video Village

Game shows of the MTV generation usually look for physical player involvement, so I’m surprised no one has thought to revive Video Village, a silly but fun series that ran from 1960 to 1962 on CBS daytime, with a brief foray into prime-time hours. Format-wise, it was pretty simple: Two players competed as life-size “pieces” on a studio-sized game board. Each would bring a friend or relative along to roll the dice for them and, based on that roll, contestants would move one to six spaces along the “street.” Some spaces paid little prizes — merchandise or money — while some spaces cost you a turn or took your prizes away. On the last of the three “streets,” the prizes became considerable…and, of course, the object of the game was to reach the finish line before your opponent.

There was also a kid’s version of the show briefly on Saturday morning. As I recall, it was called Video Village Jr. in the TV Guide and it was called Kideo Village on the show itself — or perhaps it was the other way around. I was ten at the time and bothered more than anyone should have been by this discrepancy. Years later, when I met Monty Hall, I saw my chance to finally get this age-old riddle answered and off my widdle mind. I asked him why the show had one name in TV Guide and another on the air. His reply was, “It did?” Thank you, Monty Hall. (In 1964, the same production company, Heatter-Quigley, did another kids’ version of Video Village. This one was called Shenanigans and was hosted by Stubby Kaye.)

As you can see from the tickets above, the first host of Video Village was Jack Narz and the show was done in New York. Mr. Narz then had a home and marriage in Los Angeles and both were breaking up due to his being on the opposite coast so much. As the story is told, he begged CBS to move Video Village to Hollywood and they said this was not possible…so he quit. He departed so abruptly, in fact, that the production company had to scramble to find someone to host the next day’s show. They got Monty Hall, who had never seen the program, but he learned it well enough to take over for a few weeks. There was talk of letting him keep the job but some high exec at CBS owed a favor to a performer named Red Rowe, who had drifted about their schedule, hosting various talk and game shows. Rowe took over for a while but he didn’t work out and Hall was brought back for the rest of the run.

As one can also note above, the show was done in New York at CBS’s Studio 52, which was one of their busiest. It was broadcast live when Mr. Narz was the host and it must have been a pain to put up that huge set every morning and then strike it so that something else could be done on that stage later in the day. They went to taping five a day at some point during Monty’s tenure but things still got so crowded in the various Manhattan facilities that CBS did what they’d told Jack Narz they couldn’t do: Move the show to Los Angeles. The final months were taped at Television City in Hollywood and while he was out here, Monty set up a production company and sold his first show, Your First Impression, to NBC. Other programs, including Let’s Make a Deal, would follow.

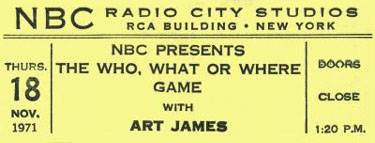

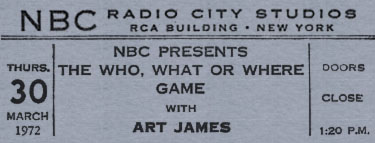

Who, What or Where Game, The

Someone described The Who, What or Where Game as Jeopardy! Lite. It was a pretty good quiz show with three contestants (usually one of them, a returning champion from the previous episode) answering not-the-easiest questions.

Host Art James would reveal a category like “Chocolate” or “World War II.” For each category, he had a “Who” question, a “What” question and a “Where” question and each question had posted odds based on its difficulty. A real tough question might have 5-to-1 odds. A real simple one might be 2-to-1 or even money. Each player would select an interrogatory pronoun and lock in a secret wager of up to $50 that he or she could answer the as-yet undisclosed question associated with it. Then the bets would be revealed. If you were the only contestant to wager on one question, you got to answer it and if you were right, the dollar amount — multiplied by the announced odds — would be added to your total. If two or three players bid on the same question then it went to the person who made the highest wager. If the wagers tied, then there’d be an auction. All the wagers would be blanked out and the players could bid for the question up to the total amount of money they had in their accounts at that moment. Totals went up and up and at the end of the show, they all got to keep what they’d won and they guy who’d won the most got to come back and face two new contestants.

There was a little more to it than that but that’s already more than you need to know. The show moved at a brisk clip and Art James was a pretty good host. It went on the air in the last week of 1969 and stayed on ’til the first week in ’74. It was one of the last game shows done on a tiny set with no bells, no whistles, no cars on stage, no prize models and minimal lighting effects. Some of that was present in The Challengers, a very similar game show hosted by Dick Clark from 1990 to 1991.

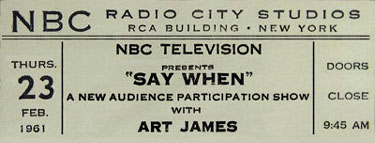

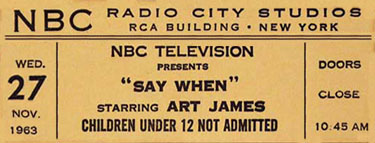

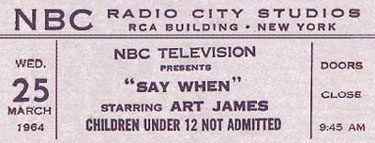

Say When

Say When was a good but unmemorable game show that seems to have been invented because The Price is Right was doing well and someone said, “Hey, people like to guess what things cost.” On Say When, two contestants would compete. Host Art James would announce a Target Price for each game and then trot out different prizes for the players to “buy.” The object was to estimate the manufacturer’s suggested retail prices for each item and select as many as possible so that your total came closer to the target price that your opponent’s picks, without going over. Along the way, you might encounter a “blank check” for some simple supermarket item like Rice-a-Roni or Buitoni spaghetti. If you got one, you could fill it out for any amount of the product up to one hundred. If you knew how much the item cost, you could “buy” just enough to get very close to the Target Price.

Among collectors of old TV shows, Say When is best remembered for the time Art James was doing a live commercial for Peter Pan peanut butter. When he put the knife in the jar to scoop out some of the product, the bottom fell out of the jar and the knife plunged through it to the floor. The audience got quite hysterical and James, trying hard not to laugh, pressed ahead with the ad pitch, adding in the suggestion that someone had been digging so fervently for this great peanut butter that they’d weakened the jar.

Say When went on the air January 3, 1961. A little more than four years later, NBC decided to say “When” and it had its final broadcast on March 26, 1965. James went on to host many other game shows, including The Who, What or Where Game and The Magnificent Marble Machine.

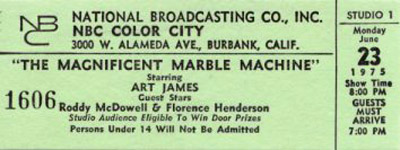

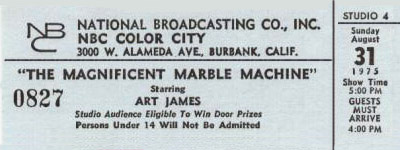

Magnificent Marble Machine, The

Pinball was big in 1975 but someone at the NBC and the game show company Heatter-Quigley didn’t seem to grasp that people liked to play it, not to watch it. In fact, it’s frustrating watching someone else do something like that because you keep thinking when you’d push the button and every time they miss, you want to elbow them aside and take over.

People also liked the new, high-tech pinball machines that were coming out and had very little interest in a huge, clunky lower-tech one called The Magnificent Marble Machine. Also, of course, the folks who were flocking to arcades to play pinball were not the housewives who had to tune in if a game show was going to be successful. So right there, you had more than enough reasons for this one to be a fast flop. Which it was.

It went on NBC in July of that year with Art James as the host and by December, the big pinball machine was in storage. Mr. James was a very good, fast-on-his-feet master of ceremonies who had hosted two modest successes in the game show field — Say When and The Who, What or Where Game. But between and after them, he had the misfortune to get hired for a string of less-than-classics. They included Blank Check, Catch Phrase, Fractured Phrases, Pick and Choose, The Shopping Game, Temptation and Pay Cards. After several in a row failed quickly, he stopped getting called for emcee jobs and returned to his previous station as a game show announcer. Not long before he retired, he had a role in Kevin Smith’s movie, Mallrats, playing — you guessed it — a game show host.

The Magnificent Marble Machine involved two teams (each with one celebrity and one civilian) competing in a question round and then the winning team got to play the big pinball machine. The question round was a bore: Clues were displayed on a screen and players had to buzz in and identify what they were describing. But the pinball machine wasn’t much more exciting. It was twenty feet high and twelve feet wide and the two players on the team had to work the flippers, keep a large ball in play and try to light up bumpers. The more bumpers that were lit up, the bigger the contestant’s winnings. But the flippers didn’t flip so well and it often felt like someone was losing out on the big money because Adrienne Barbeau couldn’t make work the controls properly.

I visited the set one time when my friends, Charlie Brill and Mitzi McCall, were the celebs. They struggled in a pre-taping practice session to learn how to make the flippers flip…but by taping time, they’d both failed to light up one bumper. “I hope nobody’s planning on winning anything today,” Charlie quipped. When they started playing for real, it almost went that way. I remember standing next to the machine during a break and having a great urge to play it, which the crew wouldn’t let me do because then they’d have to let everyone on the set play with it. Everyone wanted to…but like all of America, we had no interest in watching somebody else play it.

By the way: I like that line on the tickets that says, “Studio audience eligible to win door prizes.” Note that it doesn’t actually say that there are door prizes or that someone who attends a taping will win one. It just says that if you’re there, you’re eligible for any door prizes that might occur. The folks who played that day with Charlie and Mitzi were eligible to win things too and didn’t.

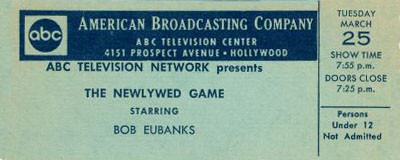

Newlywed Game, The

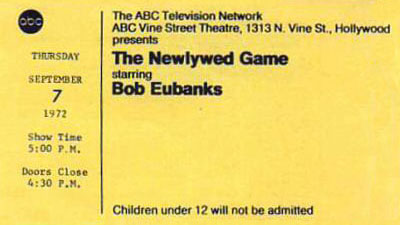

A friend of mine told me that once when he and his wife needed new furniture, they rehearsed a little routine in which they embarrassed each other by revealing “secrets” which they made up for the occasion. Like, they decided to blurt out that the husband liked to dress in the wife’s clothing, and that her cooking gave him diarrhea at least once a week. Then they went and auditioned for The Newlywed Game, quarrelling the entire time and letting such things “slip.” They were instantly booked as contestants.

Once in front of the cameras, they dropped the act and behaved like dignified human beings, despite the fact that the questions they were asked seemed calculated to evoke the humiliating stories from the audition. They left with their self-esteem relatively intact, plus a new bedroom set. They also received a tongue-lashing from the show’s Contestant Coordinator who realized they’d been “had,” and warned them that they would never get on another Chuck Barris game show as long as they lived. So far, it hasn’t bothered them too much. (The top ticket, by the way, seems to be from 1969.)

Match Game, The (1973-1982)

Not long after The Match Game went off NBC, Goodson-Todman Productions was developing a new version for CBS. Hollywood Squares, with its nine celebrities giving funny answers to questions, was then the big hit in daytime TV and the show to copy. The new format Match Game used six but as with Squares, two contestants would compete to evaluate the stars’ responses. The questions also became more likely to lead to funny, slightly naughty answers. Instead of asking people to name their favorite cheese, as he had on the old version, Rayburn would read the straight line to a joke and the celebs would have to supply the punch line.

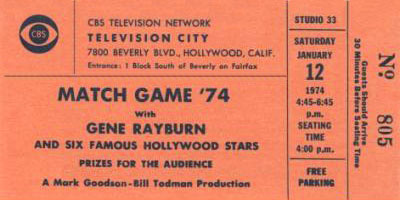

Match Game ’73 went on the air July 2, 1973. The first panel consisted of Michael Landon, Vicki Lawrence, Jack Klugman, Jo Ann Pflug, Richard Dawson and Anita Gillette. Dawson was a regular from the start…until mid-’78 when he became too busy with Family Feud — a show that seems to have been inspired by the “audience match” bonus round on Match Game. Charles Nelson Reilly and Brett Somers Klugman (ex-spouse of Jack) first appeared on the panel in the show’s third week and soon after came back as regulars.

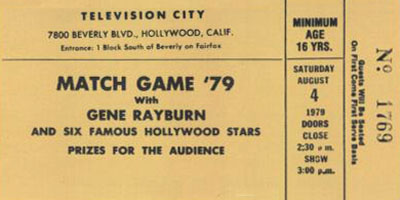

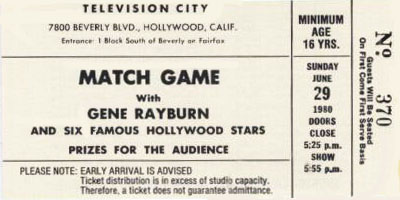

For a long time, the daytime version changed names every year — to Match Game ’74, then Match Game ’75 and so on. A once-a-week syndicated version for evenings was called Match Game PM and ran from 1975 to 1981. In 1979, CBS cancelled the daytime version and Goodson-Todman immediately offered a syndicated five-a-week version called simply Match Game, with no identifying date since shows were run and rerun at different times. (The tickets above that lack the CBS eye were from tapings for syndicated shows. CBS policy was to only put their logo on tickets for shows that aired on CBS.)

Episodes were taped in long blocks to accomodate Gene Rayburn, who commuted from a home on the East Coast. Sometimes, they’d tape six days a week, five shows a day, for two or three weeks at a stretch. That sometimes made it difficult to secure enough of an audience to fill all the seats. As you can see, the tickets promised prizes to those who came to watch. And on almost every tape day, people dispensing free tickets could be found over at Farmer’s Market, the tourist attraction located next to CBS Television City. Sometimes, they’d “sell” the evening tapings by pointing out that the celebrity panelists often got a bit tipsy over the dinner break from wine and other spirits. This is why the Thursday and Friday shows, which taped after supper, were usually funnier and full of bleeps.

Even after the syndicated version ended, Match Game did not stay off the air for long. By October of ’83, it was back on network as one half of The Match Game-Hollywood Squares Hour, thereby partnering with the show it tried to emulate in the first place. Another version ran from 1990 to 1991 and yet another from 1998 to 1999.

[Thanks to Curt Alliaume for correcting an error that was in this page as originally posted.]

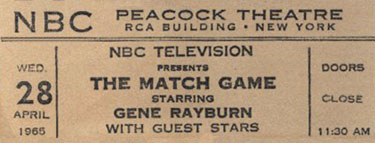

Match Game, The (1962-1969)

Here’s the first version of The Match Game, which was a simpler show, less prone to dirty answers and drunken celebrities than the revival that followed. In this one, there were two competing teams, each with a celebrity and two civilians. Host Gene Rayburn would ask a question which could have multiple answers like, “Name a great magician” or “Besides pepperoni, what’s a great topping for pizza?” All six people would write down, then unveil their answers. On each team, if two of them matched, they earned $25. If all three matched, they got $50. The first team to reach $100 won the game and a hundred dollars and the right to play the Audience Match for additional cash. The show went on the air the last day of 1962 and lasted until September of ’69. Less than four years later, the revised version went on the air as Match Game ’73.

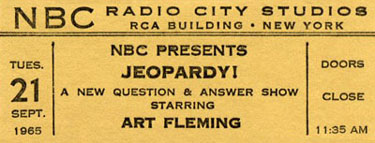

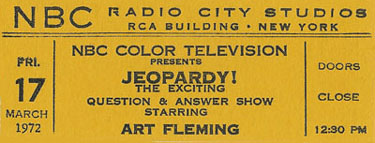

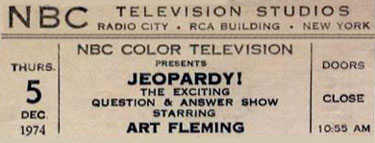

Jeopardy! (1964-1975)

A popular staple of late night comedy shows was always the bit where they give the answer and then the question. Steve Allen did it as The Question Man, and Johnny Carson did the exact same thing as Karnak the Magnificent. (“The answer is…Sis Boom Bah. The question is: Describe the sound of a sheep exploding.”) Under the contract of The Merv Griffin Show, his failed NBC afternoon talk show, Merv was owed a couple of commitments for game shows. He originally tried to assemble a comedy quiz program based on the answer-before-the-question premise but it didn’t come together. At the suggestion of his then-wife, he made it a non-comedy show and defied the notion that daytime TV viewers wanted fluff, not hard questions. In no time at all, Jeopardy! became one of the greatest success stories in the history of television. It debuted in March of 1964 and lasted on NBC until January of 1975, so the third ticket above would have been to one of the last tapings. Eleven years is a hefty run but Griffin was still angry at the time, feeling his “baby” could have run much longer.

A lady named Lin Bolen had taken over in the programming division of the network and she had definite ideas about how to reinvent the stodgy old game show. One was to jettison the “old men” who hosted many of them and bring in “young studs” as hosts. Her theory — and it made sense — was that housewives would rather look at Geoff Edwards and Alex Trebek (who were among her finds) than at Art Fleming and Dennis James. She had other theories as well, and she put them to the test when she developed a new game show called Jackpot! She put her new show in the coveted Jeopardy! time slot, moving that show to a later, less desirable hour. Both shows failed. NBC cancelled Jeopardy!…but under the terms of their contract with Griffin’s company, Merv was owed another year of some show, so he came up with Wheel of Fortune. It debuted the Monday following the last Jeopardy! with one of Bolen’s “young stud” discoveries, Chuck Woolery, as the host. In 1978, after Bolen was no longer at NBC, the network tried bringing Jeopardy! back in a slightly-glitzier format — at Griffin’s insistence, with Art Fleming — but it only lasted five months. Then in 1983, with Wheel of Fortune still doing well on NBC daytime, Griffin launched a syndicated nighttime version. It was a smash so Merv immediately revived Jeopardy!, hired Alex Trebek (one of Lin Bolen’s “young studs,” now considerably older) and sold the two shows as a package. He made a gazillion dollars.

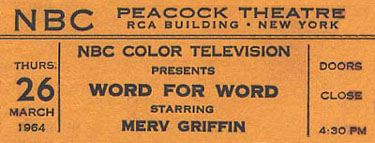

Word for Word

After The Merv Griffin Show left the NBC daytime schedule, Merv returned with a new game show from his own production company. Word for Word involved showing contestants a word and then seeing how many other words they could make using its letters. It lasted a little more than a year before going off but Merv probably didn’t care much. In the meantime, he’d sold NBC a game show called Jeopardy! and soon after, he made a deal to do his own talk show for syndication, so he did just fine. (Ticket courtesy of Brian Gari.)