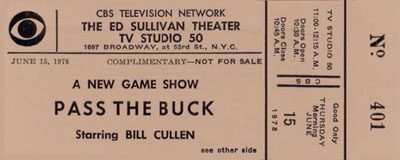

Pass the Buck

Bill Cullen hosted oodles of game shows, some of which lasted for years. Pass the Buck was one of his biggest flops, debuting on CBS in April of 1978 and disappearing thirteen weeks later.

Here’s how it worked: Four players competed, answering questions that had multiple answers like, “Name a U.S. president who served two terms” or “Name a flavor of ice cream sold at Baskin-Robbins.” If the first player gave an acceptable answer, as determined by the program’s judges, $25 was added to the bank and the play passed to the second player. If the second player took too long or gave an unacceptable answer, he or she would be eliminated if the next player answered correctly. Eventually, three of the four players would be eliminated and the remaining player would win all the money then in the bank and a chance at the bonus round which no one seemed to understand.

The producers kept fiddling with the rules, especially with that bonus round, but time ran out for Pass the Buck before they got the bugs out.

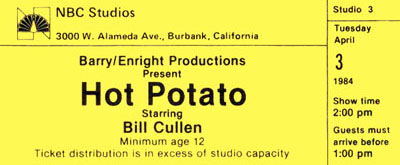

Hot Potato

Hot Potato was the last network game show hosted by Bill Cullen (he did several for syndication later) and one of his least successful. It aired on NBC from January of 1984 through June of the same year. The quiz pitted two teams against each other, each team comprised of three people who had something in common — three firemen, for example. Or three former beauty queens or something of the sort. Later, when it was clear the show wasn’t working, they abandoned that idea and each team was made up of two celebrities and a civilian, with the non-celeb taking home whatever the team won.

The game itself had a bit of Family Feud in it. The show conducted a survey on some question of vital interest like, “What’s your favorite pizza topping?” The idea then was to identify the seven most popular responses to the question. When it was your team’s turn, you could either try to answer or you could challenge someone on the opposite team to answer. If they couldn’t, they were eliminated. So your team could win the round one of two ways: You could give the seventh answer or you could knock out all three players on the opposing team. If you won two out of three games, you got to play a bonus round for more cash.

After long associations with Goodson-Todman and Bill Stewart Productions, this was Cullen’s first game show for the Barry-Enright production company. He went on to host The Joker’s Wild for them in syndication.

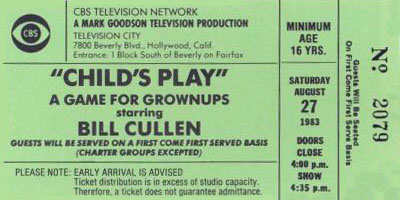

Child’s Play

Another game show hosted by Bill Cullen. This one ran on CBS for one year — September of ’82 to September of ’83. The premise was pretty simple: A film crew went out and interviewed children, asking them to define different words. In the studio, two contestants were shown excerpts from those interviews and asked to guess the word that the kiddos were discussing. It sounds better here than it did on the screen where the whole thing came off as awkward and contrived, and sometimes even a bit condescending to the children. Cullen soldiered on bravely with the show but you could almost tell that he knew this one wasn’t working. It reportedly stayed on the air as long as it did only because the network had trouble coming up with a replacement that seemed like it might fare better. When they found Press Your Luck, they said bye-bye to Child’s Play.

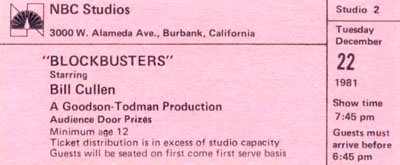

Blockbusters

Another in the seemingly-endless list of game shows hosted by Bill Cullen, Blockbusters aired on NBC from October of ’80 until April of ’82. The most unusual thing about it was that it pitted a two-person team against a single player. In order to win a round, the two-person team had to answer a few more questions than the single player, and my impression was that this didn’t happen very often. It always seemed like the single player was victorious.

The questions involved identifying words or names from initials. The player (or players) would pick a letter from the game board — “L,” for example. Cullen would then ask them, “What L would you associate with a candelabra?” The correct answer in this case was Liberace. In the bonus round, wherein serious money could be won, the questions would often be abbreviations: “This G.W.T.W. won many Academy Awards.” To that, the conestant(s) would have to answer, “Gone With the Wind.” And so on.

It was a pleasant little game, carried mainly by Mr. Cullen’s genial nature. It was not the best of the many game shows he hosted but it was one of the better ones. Not long after it went off the air, he was back on the air — this time on CBS — with Child’s Play.

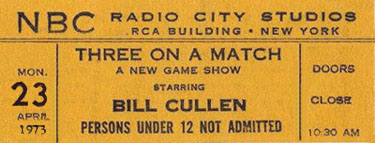

Three on a Match

A little less than two years after Eye Guess was cancelled, its producer (Bob Stewart) and host (Bill Cullen) and much of the same staff were back on NBC with Three on a Match. This one debuted in August of ’71 and lasted until June of ’74.

What was it about? That’s hard to say. It was even hard to say when it was on because the rules were complex and they kept changing. Basically, three players competed. They were shown a list of categories and they’d pick one and wager on how many true-false questions they thought they could answer in that category. With the cash they’d win by doing that, they’d buy squares on a big game board where pictures of prizes were hidden. If they revealed three matching prize pictures, they’d win that prize. Or at least, that’s how it went for a while. This was a confusing game and its producers were forever altering the rules to make it into smooth-running, simple affair.

They never quite managed that and at some point, it was apparently decided that it was easier to just chuck the whole thing and start over. So the last episode of Three on a Match aired on Friday, June 28, 1974. The following Monday, the exact same staff — including producer Stewart and star Cullen — were doing a new game show called Winning Streak in the same time slot on NBC.

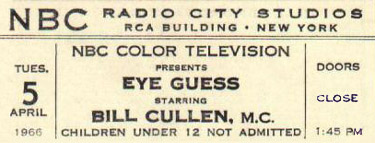

Eye Guess

Eye Guess was the first independent production of Bob Stewart, a game show producer who’d previously worked for Goodson-Todman Productions where he’d supervised and/or developed hits including To Tell the Truth, Password and the original The Price is Right. On the last of these, which had just been cancelled after its long run, Stewart worked with emcee Bill Cullen, and when Stewart struck out on his own, he tapped Cullen to host his first show.

On Eye Guess, two players confronted a game board containing nine squares like a tic-tac-toe game. In round one, they’d be shown eight possible answers to upcoming questions…but only for eight seconds. Then as Cullen asked questions, they’d call out numbers — i.e., “The answer to that one is behind Number Six, Bill!” Sometimes, the correct answer was none of the eight and if they thought that, they’d select the middle square, which was the “Eye Guess” space. If you racked up enough correct guesses, you won. Simple as that.

Eye Guess was a modest hit, lasting on NBC from January of ’66 to September of ’69. Cullen was not idle for long. The same month Eye Guess went off, Goodson-Todman revived To Tell the Truth as a daytime show and included him on its panel. Two years later, he was also back as a host…on a new NBC game show, Three on a Match, also produced by Bob Stewart.

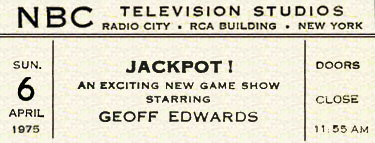

Jackpot!

Jackpot! was an extremely new game show that went on NBC in 1974…a show that was supposed to usher in a new era in daytime television. Although the series itself did not succeed, a number of its innovations did become somewhat standard in the world of game shows. One was to go for a more “open” look. Instead of a set that enclosed the action in three cramped walls, the stage was wide open with a less claustrophobic feel. The other change was to go for a younger, sexier host…someone who might appeal to housewives in a way that most of the usual hosts did not.

That host, hand-selected by NBC exec Lin Bolen, was Geoff Edwards. She rejected dozens of candidates in New York (where Jackpot! would be taped) and instead, Edwards would be flown in most weekends from Los Angeles where he did a Monday-Friday radio show on station KMPC. She also reportedly supervised a new hairstyle for Edwards, as well as a whole new wardrobe that consisted mostly of the then-popular leisure suits.

Jackpot! was about riddles. Sixteen contestants would compete for a week at a time and at any given time, one would be designated as King of the Hill (or Queen, as applicable). When you were King/Queen, the others would read you the riddles and as long as you kept answering correctly, you’d continue playing and the jackpot would continue building. When you happened on the Jackpot Riddle!, a correct answer would cause the pot to be divided between you and the person who’d asked you the riddle.

Jackpot! replaced The Who, What or Where Game on the NBC schedule but not in the same time slot. Jeopardy!, which was then NBC’s most popular daytime program, was relocated there and the Jeopardy! time slot went to the new program. As explained on our page for the displaced show, its producer — Merv Griffin — was unhappy to see his series bumped to a new time so that Bolen could give every possible chance to Jackpot!, which was one of the first shows she supervised at the network. And then Bolen was unhappy that Jackpot! failed to click with viewers. It got consistently lower ratings than Jeopardy! and went off the air in September of 1975. (Some credited the failure with costing NBC its dominance in daytime. Jeopardy! was also cancelled and thereafter, soap operas on CBS and ABC ruled the morning hours.)

But Jackpot! had two afterlives, both with essentially the same format and set. A 1985 version was produced in Canada, primarily for airing on the USA Network in this country. It was hosted by Mike Darrow and lasted until 1989. Shortly after, a third version was produced for syndication in Southern California with Edwards returning to the host position. This one went unseen in many cities and failed after one year when its distributor collapsed. All of these were produced by Bob Stewart Productions, which had better luck with different incarnations of The $10,000 Pyramid.

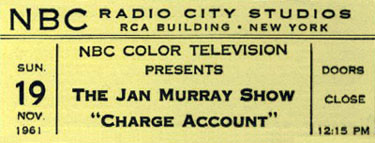

Jan Murray Show, The

What we have here is a game show where nobody particularly liked the game. When NBC cancelled Treasure Hunt, it was with the express intention of finding a better vehicle for its host, Jan Murray. He was back in a matter of weeks — as of September 5, 1960 — with Charge Account, a weak game with a good host. So as the months went on, the program became less about winning money and more about Murray chatting with the contestants. In mid-run, it was renamed The Jan Murray Show and by that point, it was at least as much talk show as game. There’d be a fun conversation and then at some point, it would come to a halt and Murray would say, with as much enthusiasm as he could muster, “Well, I guess it’s time for you to win some money.” It was not unlike the way Groucho Marx on You Bet Your Life sometimes treated the quiz part of the show as an intrusion on the entertainment.

Maybe it wouldn’t have been like that if the game itself had been better. Murray would take tiles, each of which had a letter on it, and mix them up in a drum. Then he’d pull them out as if calling Bingo and read the letters off. The contestants had Bingo-style cards in front of them and they’d attempt to form words as they wrote the letters onto their cards. After that, an English professor-type gentleman would grade their cards, awarding them so many points for each three-letter word, so many for each four-letter word and so on. Pretty boring stuff.

All the databases say that it was a half-hour show but I seem to recall either that it ran an hour for at least one week, or that some article said it was going to go to an hour. I also have the vague memory of them dumping the game completely the last few weeks and trying to keep it going as a straight talk show, which is probably what it should have been in the first place.

The “home game” of Charge Account was apparently manufactured to excess: It was well-represented in every toy store and after the show was cancelled, it was possible to buy it, at least in the stores around me, for practically nothing. Which was about what it was worth. Since it didn’t come with the one good thing about the TV show — Jan Murray’s banter — there was no reason to even open the box.

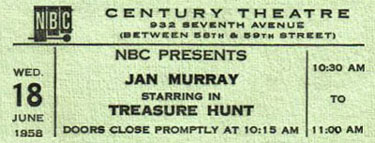

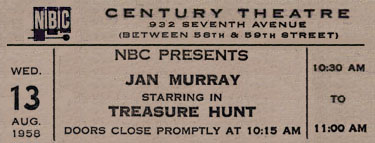

Treasure Hunt (1956-1959)

Treasure Hunt started in 1956 as a weekly prime-time game show on ABC where it lasted all of one year. But NBC liked the program and they especially liked its host, comedian Jan Murray. They snatched it up for a five-a-week daytime slot from ’57 to ’59 and also gave it another brief try in prime time in 1958.

There were three “acts” to a game of Treasure Hunt, the first being the interview segment where Jan would chat with the contestants at some length, a la Groucho Marx and You Bet Your Life. The second part was a quiz with the contestants competing against one another for the right to go on a treasure hunt. The winner could select one of thirty treasure chests on the stage, guarded by the show’s “Pirate Girl” — a lovely model in an abbreviated Jolly Roger outfit. For much of the show’s run, the Pirate Girl was starlet Greta Thyssen, fresh from a series of supporting roles in Three Stooges comedies.

Then came the final part of the show — The Tease and Reveal. The chest could contain a huge amount of money, a trip around the world, a fur coat or some other fabulous prize…or it could contain a cheap booby prize. Murray would peek inside the chest, find out (without telling the contestant) what they’d won…and then try to convince them that it was something crummy and they should swap the contents for some modest amount of cash he was offering. I remember him dragging this out for long minutes with great theatrics and every so often, he’d succeed. Against the audience’s shouted advice, the contestant would take $300 instead of what was in the chest…which would turn out to be a new car. My aunt used to watch Murray making the “winners” sweat and squirm and she’d say, “Why do they have to do that to people? Why can’t they just let them win what they win?”

As you can see from the above tickets, the show was done from the Century Theatre in New York. The Century opened in 1921 as Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre (even though it faced Seventh Avenue) and Al Jolson starred in the first production on its stage, a musical called Bombo. It became a movie house called the Central Park Theatre in 1931, then went back to live productions as the Shakespeare Theatre the following year. In 1934, it was renamed the Venice Theater and then in ’42, it went back to being Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre (even though it still was not on 59th Street) for a year before being renamed The Molly Picon Theater. That name lasted four months…or until the show starring Molly Picon closed. Then it was back to the Jolson name for a few months while it showed movies…then in 1944, it again returned to live performances as The New Century Theater. It housed plays and musicals, including High Button Shoes and Kiss Me Kate, until 1954 when NBC bought it for television use. It was finally demolished in 1962.

Treasure Hunt moved into Rockefeller Center by the summer of 1959. I know this because that was when my mother and I went to New York for a trip that included being in the audience for a broadcast of a game show. We wanted to see Treasure Hunt, which was done in the adjoining studio, but it was sold out so we got in line for our second choice, Concentration. As we stood there, Jan Murray came by in a loud, checked sport coat and bantered with all of us who were waiting. I remember that even though I’d met TV stars by then, he absolutely terrified me and at age seven, I was too shy to respond when he stuck out his hand and tried to shake mine. But I also thought it was amazingly cool that he could walk out there, get everyone laughing and generate so much excitement among the tourists.

When NBC cancelled Treasure Hunt, it was with the idea of finding a better show for Murray to host. They signed him to a long-term contract and he was soon back with a game show called The Jan Murray Show, subtitled Charge Account. Much later, Treasure Hunt was revived in a syndicated version hosted by Geoff Edwards that ran from 1973 to 1977, then returned for another year in 1981. The Edwards version dispensed with everything in the old format except for the Tease and Reveal, which they made considerably more sadistic.

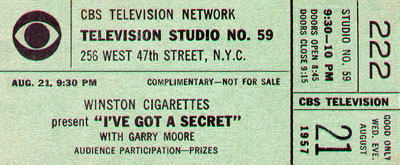

I’ve Got A Secret (1952-1967)

What’s My Line? was one of the most popular shows on TV when two out-of-work comedy writers, Howard Merrill and Allan Sherman, created a not-dissimilar show which they called I Know A Secret. They took their creation to the producers of What’s My Line?, Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, who immediately informed them it was a copy of their program. Sherman, displaying the ingenuity that would later catapult him to stardom as a singer of song parodies, replied that “People are going to start imitating your show whether you like it or not. You might as well do it and make the money.” Amazingly, Goodson and Todman saw the wisdom in this and bought the idea.

When I’ve Got A Secret went on CBS a year later, it was an immediate disaster, in part because Goodson-Todman had tried too hard to differentiate it from What’s My Line? It had an awkward courtroom set in which the panelists would walk up and interrogate the contestants seated in a witness stand. After the first broadcast, Goodson ordered the set scrapped and a new one built which would be a mirror-image of the What’s My Line? set. Also after the first broadcast, one of the show’s two sponsors cancelled so for the remainder of its first season, Secret only aired every other week, alternating with Racket Squad.

By the end of the year, the producers had gotten most of the bugs out of I’ve Got A Secret and it built up enough of a following to return to weekly status. The show had many things going for it. The program staff (mainly Allan Sherman, until he got himself fired in 1958) was fearless about trying different things and taking risks. On What’s My Line?, the panel was prim and proper and dressed in tuxedoes and evening gowns…and if the contestant’s secret occupation was that he shot apples off someone’s head, you never got to see him do it. On I’ve Got A Secret, the game would be followed by him shooting an apple off some panelist’s noggin. The show, though broadcast live, was willing to be wildly unpredictable with its odd stunts and clever “secrets.”

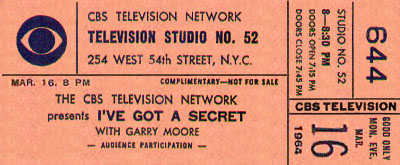

The producers also managed to eventually assemble a great panel, anchored by Bill Cullen and Henry Morgan, two of the wittiest men in television. They were good opposites: Cullen was cheery and optimistic; Morgan was acerbic and if something on the show was silly, likely to say so. The women changed from time to time but included Jayne Meadows, Faye Emerson, Betsy Palmer and Bess Myerson, all of whom were quite charming. Best of all, the show had Garry Moore as its host. A great ad-libber, he could handle any disaster — a fact which no doubt encouraged the producers to try more daring segments. Moore did a terrific job of keeping the game moving and setting up the panelists to be funny. It all made for a great weekly party, right up until 1964.

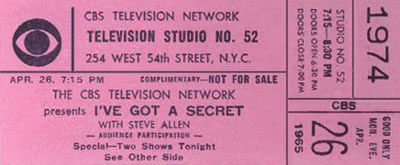

That year, CBS programming was in the hands of a man named Jim Aubrey who was known for his ruthlessness. “The Smiling Cobra,” as some called him, cancelled The Garry Moore Show — the other show Moore was doing for CBS — in such a nasty confrontation that Moore decided to also give up the game show and retire. Steve Allen was selected as his replacement on I’ve Got A Secret and he kept things afloat for three more seasons…but the chemistry wasn’t the same. Allen dominated the show more than Moore had, and you could sometimes sense that he and Henry Morgan weren’t getting along well. Also, since Steverino lived in California and commuted to New York to do the program, they began doing two shows every other week — one airing live that night, one taped to air the following week. (Note on the above ticket for an Allen-hosted episode, it says “Two shows tonight.”) In his 1994 autobiography, Henry Morgan recalled the show as hitting a ratings decline when Allen took over and being cancelled soon after. In truth, it lasted three years with Steve…but Morgan’s mistake says a lot about how it must have felt to one of the key panelists.

The original CBS version of I’ve Got a Secret was cancelled in 1967, the same year that What’s My Line? bit the dust. It was revived in 1972 for a syndicated version, also hosted by Steve Allen, which ran one year. It was revived again in 1976, hosted by Bill Cullen, for a brief summer fill-in run. It was revived again in 2000 for the Oxygen Network in a version hosted by Stephanie Miller. And yet another version, hosted by Bill Dwyer, ran on GSN in 2006.

[NOTE: The second ticket above was donated to this site by Brian Gari. Had you used it to attend the broadcast on 3/16/64, you would have seen special guest star Olivia DeHaviland try to stump the panel with a secret.]