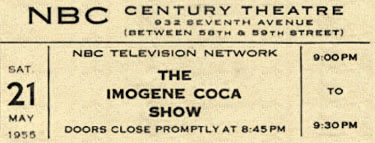

Imogene Coca Show, The

In 1954, for reasons the folks involved could never quite explain, a decision was made to break up NBC’s powerful Saturday night variety series, Your Show of Shows. Its male star, Sid Caesar, moved on to a similar program called Caesar’s Hour. Its producer, Max Liebman, began a run of specials, many of them reviving old Broadway shows. And the female star, Imogene Coca, starred in The Imogene Coca Show for what turned out to be a disappointing one season. It was done from the Century Theatre in New York, sharing space with the Wally Cox sitcom, Mr. Peepers. (The Mr. Peepers ticket we have posted is from the same month as the above Imogene Coca Show ticket.)

Though the public still loved Coca, they didn’t love her new show which started life as a situation comedy, turned into a variety show, then went back to the sitcom format. She had a strong supporting cast that at various times included Billy DeWolfe, Bibi Osterwald, Hal March and David Burns, and several of the Your Show of Show writers, including Danny Simon, Mel Brooks and Lucille Kallen. But it just didn’t work, which made 1955 a sad year for Coca. Her show was cancelled and then her husband passed away.

She disappeared from television for several years after that, finally returning in 1958 for a reunion series with Caesar, and later starring in a new sitcom, Grindl, in 1963. Some people still consider her the best comedienne to ever appear on television.

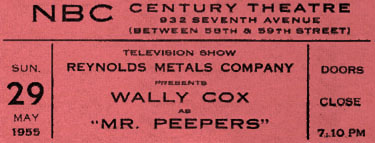

Mr. Peepers

One of the first successful TV situation comedies not derived from a radio show was Mr. Peepers, which starred Wally Cox as a shy science teacher named Robinson Peepers. It went on the air July 3, 1952 as a summer replacement and received such high ratings and good reviews that NBC quickly added it to the Fall, 1952 schedule. The recipient of one Peabody Award and eight Emmy nominations, the series remained on the air until June 12, 1955…so the above ticket is from one of the last broadcasts.

The supporting cast included Joseph Foley, Tony Randall, Norma Crane, David Tyrell and Marion Lorne. Randall played the brash history teacher, Harvey Weskit, who was everything Peepers wasn’t: Outgoing, bold, and almost sufferingly self-confident. Like all the other teachers at Jefferson High School, he wanted to help the introverted Peepers, and his advice usually resulted in things getting a lot worse. Cox was delightful and utterly convincing in the role…an achievement that seems to have caused the actor vast amounts of personal pain. He was forever typed as a meek milquetoast, a personality he insisted was quite unlike his true self. In several interviews later in life, he loudly proclaimed that he hated Mr. Peepers and was sorry he’d ever done the show.

Mr. Peepers was performed live each week from the Century Theatre in New York. For a rundown of the history of this building, see the listing for the game show, Treasure Hunt.

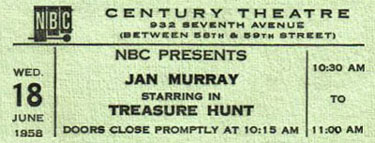

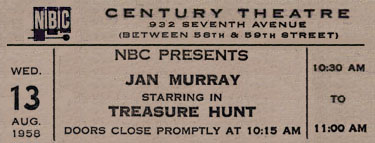

Treasure Hunt (1956-1959)

Treasure Hunt started in 1956 as a weekly prime-time game show on ABC where it lasted all of one year. But NBC liked the program and they especially liked its host, comedian Jan Murray. They snatched it up for a five-a-week daytime slot from ’57 to ’59 and also gave it another brief try in prime time in 1958.

There were three “acts” to a game of Treasure Hunt, the first being the interview segment where Jan would chat with the contestants at some length, a la Groucho Marx and You Bet Your Life. The second part was a quiz with the contestants competing against one another for the right to go on a treasure hunt. The winner could select one of thirty treasure chests on the stage, guarded by the show’s “Pirate Girl” — a lovely model in an abbreviated Jolly Roger outfit. For much of the show’s run, the Pirate Girl was starlet Greta Thyssen, fresh from a series of supporting roles in Three Stooges comedies.

Then came the final part of the show — The Tease and Reveal. The chest could contain a huge amount of money, a trip around the world, a fur coat or some other fabulous prize…or it could contain a cheap booby prize. Murray would peek inside the chest, find out (without telling the contestant) what they’d won…and then try to convince them that it was something crummy and they should swap the contents for some modest amount of cash he was offering. I remember him dragging this out for long minutes with great theatrics and every so often, he’d succeed. Against the audience’s shouted advice, the contestant would take $300 instead of what was in the chest…which would turn out to be a new car. My aunt used to watch Murray making the “winners” sweat and squirm and she’d say, “Why do they have to do that to people? Why can’t they just let them win what they win?”

As you can see from the above tickets, the show was done from the Century Theatre in New York. The Century opened in 1921 as Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre (even though it faced Seventh Avenue) and Al Jolson starred in the first production on its stage, a musical called Bombo. It became a movie house called the Central Park Theatre in 1931, then went back to live productions as the Shakespeare Theatre the following year. In 1934, it was renamed the Venice Theater and then in ’42, it went back to being Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre (even though it still was not on 59th Street) for a year before being renamed The Molly Picon Theater. That name lasted four months…or until the show starring Molly Picon closed. Then it was back to the Jolson name for a few months while it showed movies…then in 1944, it again returned to live performances as The New Century Theater. It housed plays and musicals, including High Button Shoes and Kiss Me Kate, until 1954 when NBC bought it for television use. It was finally demolished in 1962.

Treasure Hunt moved into Rockefeller Center by the summer of 1959. I know this because that was when my mother and I went to New York for a trip that included being in the audience for a broadcast of a game show. We wanted to see Treasure Hunt, which was done in the adjoining studio, but it was sold out so we got in line for our second choice, Concentration. As we stood there, Jan Murray came by in a loud, checked sport coat and bantered with all of us who were waiting. I remember that even though I’d met TV stars by then, he absolutely terrified me and at age seven, I was too shy to respond when he stuck out his hand and tried to shake mine. But I also thought it was amazingly cool that he could walk out there, get everyone laughing and generate so much excitement among the tourists.

When NBC cancelled Treasure Hunt, it was with the idea of finding a better show for Murray to host. They signed him to a long-term contract and he was soon back with a game show called The Jan Murray Show, subtitled Charge Account. Much later, Treasure Hunt was revived in a syndicated version hosted by Geoff Edwards that ran from 1973 to 1977, then returned for another year in 1981. The Edwards version dispensed with everything in the old format except for the Tease and Reveal, which they made considerably more sadistic.

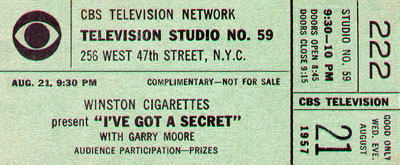

I’ve Got A Secret (1952-1967)

What’s My Line? was one of the most popular shows on TV when two out-of-work comedy writers, Howard Merrill and Allan Sherman, created a not-dissimilar show which they called I Know A Secret. They took their creation to the producers of What’s My Line?, Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, who immediately informed them it was a copy of their program. Sherman, displaying the ingenuity that would later catapult him to stardom as a singer of song parodies, replied that “People are going to start imitating your show whether you like it or not. You might as well do it and make the money.” Amazingly, Goodson and Todman saw the wisdom in this and bought the idea.

When I’ve Got A Secret went on CBS a year later, it was an immediate disaster, in part because Goodson-Todman had tried too hard to differentiate it from What’s My Line? It had an awkward courtroom set in which the panelists would walk up and interrogate the contestants seated in a witness stand. After the first broadcast, Goodson ordered the set scrapped and a new one built which would be a mirror-image of the What’s My Line? set. Also after the first broadcast, one of the show’s two sponsors cancelled so for the remainder of its first season, Secret only aired every other week, alternating with Racket Squad.

By the end of the year, the producers had gotten most of the bugs out of I’ve Got A Secret and it built up enough of a following to return to weekly status. The show had many things going for it. The program staff (mainly Allan Sherman, until he got himself fired in 1958) was fearless about trying different things and taking risks. On What’s My Line?, the panel was prim and proper and dressed in tuxedoes and evening gowns…and if the contestant’s secret occupation was that he shot apples off someone’s head, you never got to see him do it. On I’ve Got A Secret, the game would be followed by him shooting an apple off some panelist’s noggin. The show, though broadcast live, was willing to be wildly unpredictable with its odd stunts and clever “secrets.”

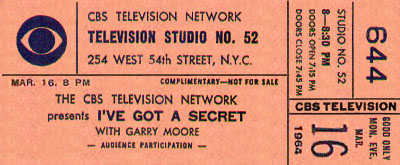

The producers also managed to eventually assemble a great panel, anchored by Bill Cullen and Henry Morgan, two of the wittiest men in television. They were good opposites: Cullen was cheery and optimistic; Morgan was acerbic and if something on the show was silly, likely to say so. The women changed from time to time but included Jayne Meadows, Faye Emerson, Betsy Palmer and Bess Myerson, all of whom were quite charming. Best of all, the show had Garry Moore as its host. A great ad-libber, he could handle any disaster — a fact which no doubt encouraged the producers to try more daring segments. Moore did a terrific job of keeping the game moving and setting up the panelists to be funny. It all made for a great weekly party, right up until 1964.

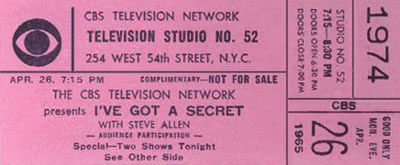

That year, CBS programming was in the hands of a man named Jim Aubrey who was known for his ruthlessness. “The Smiling Cobra,” as some called him, cancelled The Garry Moore Show — the other show Moore was doing for CBS — in such a nasty confrontation that Moore decided to also give up the game show and retire. Steve Allen was selected as his replacement on I’ve Got A Secret and he kept things afloat for three more seasons…but the chemistry wasn’t the same. Allen dominated the show more than Moore had, and you could sometimes sense that he and Henry Morgan weren’t getting along well. Also, since Steverino lived in California and commuted to New York to do the program, they began doing two shows every other week — one airing live that night, one taped to air the following week. (Note on the above ticket for an Allen-hosted episode, it says “Two shows tonight.”) In his 1994 autobiography, Henry Morgan recalled the show as hitting a ratings decline when Allen took over and being cancelled soon after. In truth, it lasted three years with Steve…but Morgan’s mistake says a lot about how it must have felt to one of the key panelists.

The original CBS version of I’ve Got a Secret was cancelled in 1967, the same year that What’s My Line? bit the dust. It was revived in 1972 for a syndicated version, also hosted by Steve Allen, which ran one year. It was revived again in 1976, hosted by Bill Cullen, for a brief summer fill-in run. It was revived again in 2000 for the Oxygen Network in a version hosted by Stephanie Miller. And yet another version, hosted by Bill Dwyer, ran on GSN in 2006.

[NOTE: The second ticket above was donated to this site by Brian Gari. Had you used it to attend the broadcast on 3/16/64, you would have seen special guest star Olivia DeHaviland try to stump the panel with a secret.]

Walter Winchell Show, The

By 1956, when The Walter Winchell Show went on the air, its star was no longer the all-powerful newspaper columnist he had once been. There had been a time when a mention in Winchell’s syndicated gossip/news column would make a career and a pan would destroy it. But newspapers were losing their clout and TV networks were establishing real news divisions. Winchell’s excited delivery had sounded gripping on his radio broadcasts but when he transferred his act to television, he looked silly — an old man reading copy and yelling, pounding randomly on a telegraph key.

Another newspaper columnist, Ed Sullivan, was a success with a variety show on CBS. Sullivan and Winchell loathed each other from past feuds, and some said Winchell was consumed with envy that his old rival was a hit where he was not. The Walter Winchell Show was supposed to rectify that but it was a flop from its first broadcast on October 5, 1956. Unlike Sullivan, who introduced the top acts and then got out of the way, Winchell fancied himself a hoofer and insisted on performing. He also found himself unable to get big stars to appear, as he’d promised the network he could. Ten years earlier, he could have snapped his fingers and had anyone in show business. By ’56, not only did few stars see any reason to curry favor with Winchell (and perhaps alienate Sullivan) but many were still mad at him for things he’d printed about them in the past.

The above ticket is probably from the show’s last New York telecast. In desperation, it was moved to Hollywood in the hope that he could round up stars on that coast. John Wayne showed up, telling reporters who asked, “Walter’s been nice to me for years. It’s about time I kissed his ass.” But Wayne was about the only biggie who appeared and the series was cancelled after thirteen weeks — a humiliating failure. The following year, Walter tried again with The Walter Winchell Files, a cop show anthology based allegedly on cases Winchell had covered in his newspaper days. Another one season disappointment. For all his fame in newspapers and on radio, Walter Winchell was only involved in one success on television. From 1959 to 1963, he was the narrator of the TV series, The Untouchables.

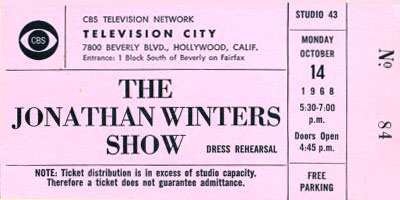

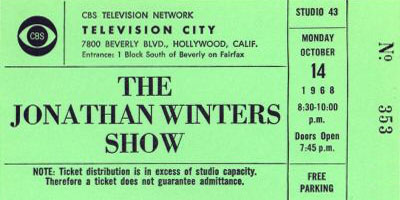

Jonathan Winters Show, The (1967-1969)

I doubt there’s a comedian anywhere who doesn’t hail Jonathan Winters as one of the greats, and whenever I’ve been around the man, I’ve seen an unending stream of people stop to tell him he’s the funniest man alive. With such unanimity of opinion, it’s amazing that Winters hasn’t had more steady work on television. What he does, he does better than anyone…but producers have sometimes been unable to package it in a format that fit neatly into a TV schedule.

The first Jonathan Winters Show was a fifteen-minute program that ran from 1956 to 1957 on NBC, following the evening newscast which then was fifteen minutes in length. It lasted about nine months.

In the mid-sixties, Winters starred in a string of network specials that got high ratings and good reviews, and appeared as a semi-regular on The Andy Williams Show. It all led to CBS, in 1967, installing him in the second Jonathan Winters Show. Most of the show consisted of sketches in which Winters played characters from his repertoire, especially the irrepressible Maude Frickert. Comedian Dick Curtis appeared in most sketches, usually as straight man, and one of the show’s producers, John Aylesworth, functioned as announcer and occasional performer. In addition to them, a number of stars turned up often enough to be considered semi-regulars: Abby Dalton, Paul Lynde, Alice Ghostley, Minnie Pearl and Cliff “Charley Weaver” Arquette.

The highlight of most episodes was the opening, which pretty much consisted of Jonathan standing on stage, letting the audience suggest characters and scenes for him to improvise. Folks at the network suggested that the staff devise some good premises and have them planted among the legitimate suggestions, but Jonathan insisted that not be done. A friend of mine who worked on the show said it wasn’t done and it wasn’t necessary…though of course, they did tape much more than was needed and edit it down for air.

The two above tickets are for the dress rehearsal and taping for the episode produced on October 14, 1968, midway through its second and final season. Later, Winters starred in several other shows, specials and unsuccessful pilots but there never seemed to be a permanent home on TV for the funniest man alive. Our loss.

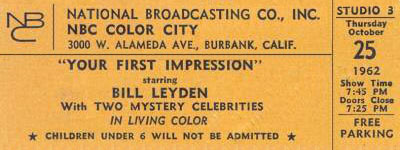

Your First Impression

Monty Hall sold his first game show as a producer to NBC in 1962. It went on the air in January of that year, more or less replacing It Could Be You, inherting the host of that show, Bill Leyden, and its producer, Stefan Hatos. Your First Impression was based on the semi-psychological exercise of asking people questions to which they’re expected to reply with the first thing that comes into their minds. A typical question might be to finish the sentence, “The thing I don’t do well is…” Or “If I could do any other job in the world, I’d be a…”

There were occasional variations in the format but the main game involved bringing on a mystery celebrity and asking him or her questions of that nature. A celebrity panel was given the name of five possible contenders and based on the responses, they had to figure out which of the five was present in the studio with them. Once, the mystery celeb was Richard Nixon, who was asked to complete the sentence, “I wish I’d been…” and who gave it away when he came back with “…the captain of a P.T. boat.”

Leyden was a cheery, laid-back gent who kept things moving nicely but who had health problems that caused him to miss the show from time to time. Monty Hall filled in occasionally and then Dennis James, who was often on the celebrity panel, took over as host for an extended period. The show went off the air in 1964, by which time Mr. Hall was quite busy. In the interim, he and Stefan Hatos had formed a production company together and sold a show called Let’s Make a Deal.

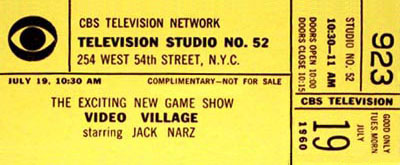

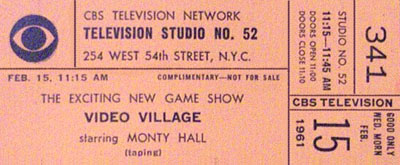

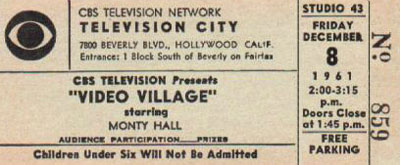

Video Village

Game shows of the MTV generation usually look for physical player involvement, so I’m surprised no one has thought to revive Video Village, a silly but fun series that ran from 1960 to 1962 on CBS daytime, with a brief foray into prime-time hours. Format-wise, it was pretty simple: Two players competed as life-size “pieces” on a studio-sized game board. Each would bring a friend or relative along to roll the dice for them and, based on that roll, contestants would move one to six spaces along the “street.” Some spaces paid little prizes — merchandise or money — while some spaces cost you a turn or took your prizes away. On the last of the three “streets,” the prizes became considerable…and, of course, the object of the game was to reach the finish line before your opponent.

There was also a kid’s version of the show briefly on Saturday morning. As I recall, it was called Video Village Jr. in the TV Guide and it was called Kideo Village on the show itself — or perhaps it was the other way around. I was ten at the time and bothered more than anyone should have been by this discrepancy. Years later, when I met Monty Hall, I saw my chance to finally get this age-old riddle answered and off my widdle mind. I asked him why the show had one name in TV Guide and another on the air. His reply was, “It did?” Thank you, Monty Hall. (In 1964, the same production company, Heatter-Quigley, did another kids’ version of Video Village. This one was called Shenanigans and was hosted by Stubby Kaye.)

As you can see from the tickets above, the first host of Video Village was Jack Narz and the show was done in New York. Mr. Narz then had a home and marriage in Los Angeles and both were breaking up due to his being on the opposite coast so much. As the story is told, he begged CBS to move Video Village to Hollywood and they said this was not possible…so he quit. He departed so abruptly, in fact, that the production company had to scramble to find someone to host the next day’s show. They got Monty Hall, who had never seen the program, but he learned it well enough to take over for a few weeks. There was talk of letting him keep the job but some high exec at CBS owed a favor to a performer named Red Rowe, who had drifted about their schedule, hosting various talk and game shows. Rowe took over for a while but he didn’t work out and Hall was brought back for the rest of the run.

As one can also note above, the show was done in New York at CBS’s Studio 52, which was one of their busiest. It was broadcast live when Mr. Narz was the host and it must have been a pain to put up that huge set every morning and then strike it so that something else could be done on that stage later in the day. They went to taping five a day at some point during Monty’s tenure but things still got so crowded in the various Manhattan facilities that CBS did what they’d told Jack Narz they couldn’t do: Move the show to Los Angeles. The final months were taped at Television City in Hollywood and while he was out here, Monty set up a production company and sold his first show, Your First Impression, to NBC. Other programs, including Let’s Make a Deal, would follow.

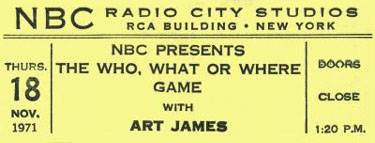

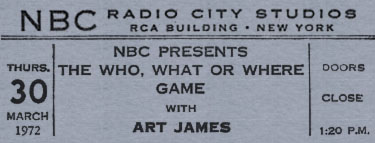

Who, What or Where Game, The

Someone described The Who, What or Where Game as Jeopardy! Lite. It was a pretty good quiz show with three contestants (usually one of them, a returning champion from the previous episode) answering not-the-easiest questions.

Host Art James would reveal a category like “Chocolate” or “World War II.” For each category, he had a “Who” question, a “What” question and a “Where” question and each question had posted odds based on its difficulty. A real tough question might have 5-to-1 odds. A real simple one might be 2-to-1 or even money. Each player would select an interrogatory pronoun and lock in a secret wager of up to $50 that he or she could answer the as-yet undisclosed question associated with it. Then the bets would be revealed. If you were the only contestant to wager on one question, you got to answer it and if you were right, the dollar amount — multiplied by the announced odds — would be added to your total. If two or three players bid on the same question then it went to the person who made the highest wager. If the wagers tied, then there’d be an auction. All the wagers would be blanked out and the players could bid for the question up to the total amount of money they had in their accounts at that moment. Totals went up and up and at the end of the show, they all got to keep what they’d won and they guy who’d won the most got to come back and face two new contestants.

There was a little more to it than that but that’s already more than you need to know. The show moved at a brisk clip and Art James was a pretty good host. It went on the air in the last week of 1969 and stayed on ’til the first week in ’74. It was one of the last game shows done on a tiny set with no bells, no whistles, no cars on stage, no prize models and minimal lighting effects. Some of that was present in The Challengers, a very similar game show hosted by Dick Clark from 1990 to 1991.

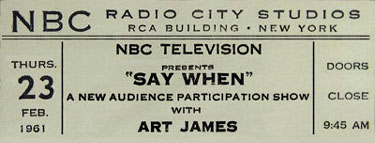

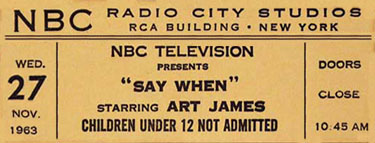

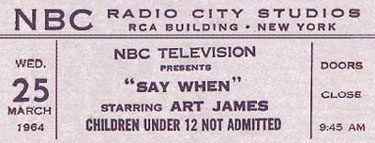

Say When

Say When was a good but unmemorable game show that seems to have been invented because The Price is Right was doing well and someone said, “Hey, people like to guess what things cost.” On Say When, two contestants would compete. Host Art James would announce a Target Price for each game and then trot out different prizes for the players to “buy.” The object was to estimate the manufacturer’s suggested retail prices for each item and select as many as possible so that your total came closer to the target price that your opponent’s picks, without going over. Along the way, you might encounter a “blank check” for some simple supermarket item like Rice-a-Roni or Buitoni spaghetti. If you got one, you could fill it out for any amount of the product up to one hundred. If you knew how much the item cost, you could “buy” just enough to get very close to the Target Price.

Among collectors of old TV shows, Say When is best remembered for the time Art James was doing a live commercial for Peter Pan peanut butter. When he put the knife in the jar to scoop out some of the product, the bottom fell out of the jar and the knife plunged through it to the floor. The audience got quite hysterical and James, trying hard not to laugh, pressed ahead with the ad pitch, adding in the suggestion that someone had been digging so fervently for this great peanut butter that they’d weakened the jar.

Say When went on the air January 3, 1961. A little more than four years later, NBC decided to say “When” and it had its final broadcast on March 26, 1965. James went on to host many other game shows, including The Who, What or Where Game and The Magnificent Marble Machine.