Haggis Baggis

Haggis Baggis was a game show that was on for one year — from June 20, 1958 ’til June 19, 1959 — during which time it almost had more hosts than viewers. There was a prime-time version hosted by Jack Linkletter and a daytime version hosted by Fred Robbins and then Dennis James. Contestants faced a game board with a celebrity’s photo concealed behind 25 squares. They could uncover portions of the photo by naming item in different categories and the first person to identify the celeb won…and if it sounds kinda silly, it apparently was. Dennis James, who hosted an awful lot of game shows, once called it the worst one he’d ever worked on. When you consider how bad some of those programs were, you get a hint as to why, in addition to the weird name, Haggis Baggis wasn’t around for very long.

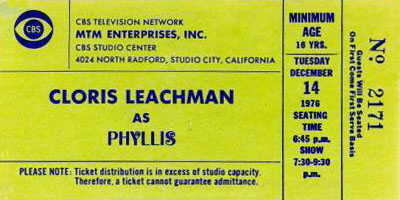

Phyllis

Rhoda got a spin-off series from The Mary Tyler Moore Show so why not Phyllis? Rhoda started in ’74 and Phyllis, starring Cloris Leachman, debuted on September 11, 1975.

The premise: Her husband Lars had died. She and her daughter Bess (played by Lisa Gerritsen) moved from Minneapolis to her old home town of San Francisco, where his mother (played by Jane Rose) and stepfather (played by Henry Jones) still resided. Beyond that, the supporting cast changed from time to time as the writers struggled to find the kind of “family” that was the norm in sitcoms from the MTM Company. They never quite made it. Even with occasional cameos from the old Mary Tyler Moore Show cast, Phyllis only lasted two seasons…and probably would have run one, had it not come with such a promising pedigree.

My favorite moment in the series occurred in the first series when the cast included Richard Schaal, playing a guy who wasn’t the brightest of bulbs. In one episode, Bess was dating (and talking about marriage to) a boy of normal height but whose parents were played by well-known “little people” Billy Barty and Patti Maloney. Phyllis was creeped-out at the genetic possibilities if Bess and the lad married and had children and was acting more nervous than usual. Schaal’s character asked her what was wrong. She replied, “Bess wants to marry a boy whose parents are midgets!”

Schaal responded, “Well, I hope she finds one.” Big laugh.

Cloris/Phyllis said, “No, no. Bess is dating a boy whose parents are midgets!”

Schaal: “Well then, there’s no problem!” Even bigger laugh. If they’d had more like that, the show might have lasted longer.

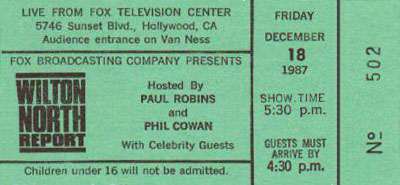

Wilton North Report

The Late Show With Joan Rivers was the first attempt by the then-new Fox Network to launch late night programming in competion with the seemingly-indestructible Johnny Carson. When Ms. Rivers crashed and burned, she disappeared suddenly from the show and was replaced by a couple of guest hosts while Fox scurried to come up with something else for the time slot. Just when Arsenio Hall began clicking as host of The Late Show, the new program was ready…and Arsenio fled elsewhere, becoming (for a time) a lot more successful than his replacement on Fox and giving Mr. Carson a brief, unprecedented dosage of competion.

The new Fox show was the Wilton North Report — which, like the earlier mock sitcom Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, drew its name from the geography near the studio. Ms. Hartman lived in Fernwood, a street which bordered the KTTV Studios. Wilton was another such street and it seemed like a dandy name to hang on a show of fake news. Similar in concept to the later, successful Daily Show on Comedy Central, the Wilton North Report didn’t look like such a hot idea when it debuted. Its hosts, Phil Cowan and Paul Robins, were disc jockeys with little TV experience. The producer, Barry Sand, had plenty having once produced David Letterman’s show in New York. The writing staff (which included a novice named Conan O’Brien) later faulted Sand for watering down the show and chopping out the best and most controversial moments.

The Wilton North Report debuted December 11, 1987. It was gone less than four weeks later but its ticket remains.

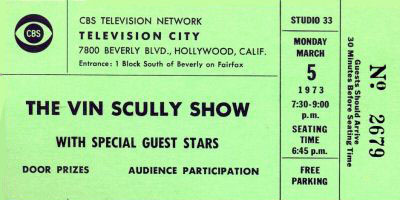

Vin Scully Show, The

In 1973, CBS tried to compete with the popular afternoon talk show then hosted by Mike Douglas. Their candidate to take on Mike? Vin Scully, then (as now) the voice of the Los Angeles Dodgers…a man often called the best sportscaster in the business.

Scully was much-loved in Southern California and a seasoned broadcaster. The only argument against him as the host of such a show was that when summer rolled around, he’d be off calling play-by-play and unavailable to tape shows on a daily basis. Reportedly, the folks at CBS thought he was such a good candidate for the post that they decided not to let a little thing like that dissuade them. The show went on the air in January of ’73 (January 15 to be exact) and the thought was that they’d worry about conflicts in Mr. Scully’s schedule later.

As it turned out, it wasn’t necessary. Scully’s show only lasted thirteen weeks, exiting the CBS daytime lineup on March 23 with new game shows taking over the time slot. The Old Redhead, as some called Scully, wasn’t all that comfy interviewing folks who didn’t have a good fastball. When sports figures came on, he was fine. With comedians and movie stars? Not so fine. So Vin scurried back to the broadcast booth and the show was quickly forgotten.

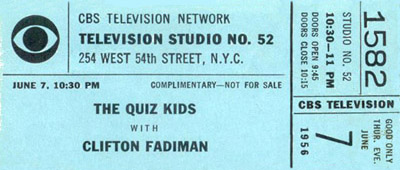

Quiz Kids (1949-1956)

Quiz Kids was a radio show that lasted an amazingly long time when you consider that people really don’t like to listen to smart children. But that’s what it was all about: A quiz program with a panel of very bright kids who often seemed more intelligent than most of the adult viewership.

The radio version debuted in 1940, broadcast from Chicago, and continued until 1953. The TV version started in 1949 and lasted until 1956. Both versions were on and off the air multiple times and even changed networks at least once, and the host was changed several times. It was often used as a replacement show, either as a summer replacement or as a quick substitute for something that had to be cancelled in a hurry.

The kids, of course, changed from season to season. The original rules gave sixteen as the maximum age but at times, the producers would decide that younger contestants were more interesting and they’d “retire” a player well before his or her birthday.

The above ticket is from 1956, near the end of the show’s TV run. By this point, it was on Thursday evenings at 10:30 PM, requiring the kids to stay up pretty late. The host then was Clifton Fadiman, a literary figure who gained great prominence in the forties for hosting or occasionally appearing on the panels of game shows. His biggest hit on radio, which he emceed, was Information Please, one of those quiz programs where you really had to know something in order to win. On TV, he hosted many shows but the most popular was This is Show Business.

Quiz Kids was revived several times after, including a 1978 version hosted by Jim McKrell, a 1981 version hosted by Norman Lear and a 1990 version hosted by Jonathan Prince.

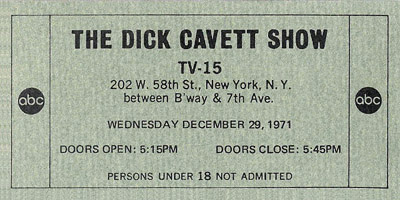

Dick Cavett Show, The (1969-1974)

There have been quite a few programs called The Dick Cavett Show but with the exception of one ill-fated attempt at variety, they were all pretty much the same: Cavett sitting around, talking to interesting people. Cavett had previously worked as a writer for both Jack Paar and Johnny Carson, and he seemed to have absorbed the better qualities of each without the worst. He had Paar’s love of conversation but not the same penchant for feuds and self-pity, and he had Carson’s comic instincts without the occasional leering qualities. On the downside, he sometimes had an “I’m smarter than you” attitude that alienated some viewers and there was often the subtext of, “Look at all the famous people I hang out with.” Neither was fatal and on the whole, Mr. Cavett did a very fine show.

It’s unfortunately lumped in with the long list of talk shows that tried to compete with Johnny and failed, and some of the articles about Cavett make it sound like he was in and out of the time slot in thirteen weeks or less. He was actually on for almost five years which, given how highly competitive it was to be on then at 11:30, is quite an accomplishment. The show was also critically-acclaimed and won awards at a time when that could be said of very little on ABC.

In 1973, ABC was enjoying some ratings success in prime-time and the execs there became infatuated with the idea that they could also win in late night. They began monkeying with the 11:30 slot, moving Cavett into a rotating format that performed worse than what it replaced. The other main component of this round-robin was Jack Paar Tonite, which failed and took Cavett’s show with it, which was our loss. Cavett went on to other, similar shows in other venues.

The above ticket says the show was done from something called TV-15. It was one of those theaters in New York that changed names and functions from year to year. It started life as the John Golden Theater in 1926 and was the Elysee the last time it housed plays. Dozens of different TV shows (including one of Merv Griffin’s) were done there in the fifties and sixties. Not long after Cavett vacated, it was turned into a church (which it had been occasionally before) and it was finally demolished in 1985.

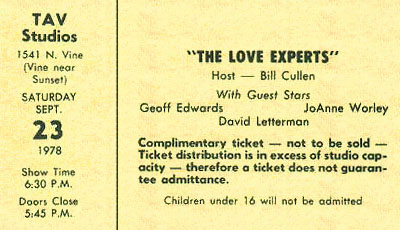

Love Experts, The

Another in the endless series of game shows hosted by Bill Cullen, The Love Experts was an awkward attempt to combine a game show with a talk/advice show. In each episode, three contestants would appear — one after the other — to talk about their romantic problems and to seek advice from that day’s panel of four celebrities. The expertise was a little dicey. Even assuming you’d want to talk about your love life on national TV, would you want counsel from Joanne Worley? Soupy Sales? Elaine Joyce? Nipsey Russell? Peter Lawford? At least some of those people should have been seeking advice instead of giving it.

As you can see from the above ticket, even David Letterman was one of the alleged experts. This was from a brief period when Mr. Letterman was making the rounds of game shows, usually acting like he didn’t want to be there, wherever he was. I suspect his advice to the lovelorn, even if he didn’t express it on the air, was to not seek advice from people like himself.

Producer Bob Stewart had previously taped and been unable to sell a pilot of this show hosted by Jack Cassidy…and hey, there’s a guy who didn’t have a single problem in his love life. When Cullen was brought in, he was doing double-shifts, simultaneously hosting The $25,000 Pyramid, also produced by Stewart. Bill did his best to keep the proceedings moving, and the show actually lasted a whole year in syndication (September of ’78 through September of ’79) though it didn’t air in many of the major markets. The “game” part came at the end when the celebs would vote to award a big prize to the person who had the most interesting story, which generally meant the most pathetic one. My main recollection of the program is that the romantic problems that the contestants offered up sounded phony and contrived. If they weren’t fabricated by the show’s producers, they were probably phonied up by the contestants hoping to win the big prize.

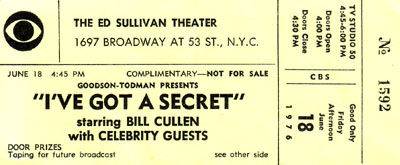

I’ve Got A Secret (1976)

In 1976, CBS revived the long-running game show I’ve Got A Secret for what turned out to be a short-running “filler” in their schedule. Bill Cullen, who’d been a panelist on the first version, moved over to the host’s chair. Henry Morgan, who’d also been a panelist on the original version, returned to his old chair and he was joined by Richard Dawson, Elaine Joyce and New York entertainment reporter Pat Collins. In format, it was identical to I’ve Got A Secret as hosted by Garry Moore but the longevity was not there. The Cullen version lasted but six weeks and since it was on opposite Happy Days at the peak of that show’s popularity, almost no one tuned in or even knew it was on.

Cullen was, of course, a fine host…probably the best choice they could have made since Garry Moore, who was then hosting the daytime To Tell The Truth, declined the post. (Not long afterwards, Moore retired completely from television.) On the old show, Cullen and Morgan had occasionally filled in for Moore but neither had gotten the position when ol’ Garry left that version. Morgan, it was felt, was better suited to be a panelist where his acerbic remarks — which occasionally suggested that something on the show was stupid — were more appropriate. Cullen was, of course, a great host but at the time of Moore’s departure from the original show, Bill was also hosting The Price is Right on ABC. That network didn’t mind him continuing as a panelist on a rival web’s show but discouraged him hosting over there…so Steve Allen took over I’ve Got A Secret.

There had also been another problem with having Cullen take over for Moore. It was a poorly-kept secret that Bill Cullen, star of countless TV programs, had a bad limp, the result of a childhood bout with polio. He didn’t demand that it never be mentioned (although some articles and bios did blame it on an auto accident) but suggested that no special attention be called to it, and that, of course, he not be placed in situations where he’d have to stand or walk a lot on camera. The shows he did were generally designed to accommodate this. He would usually not make an entrance at the beginning of the show or if he did, it would only be a step or two. If he had to walk — as he did when he entered as a panelist on the Moore-hosted To Tell The Truth — the director would cut around the action as much as possible so as to not show Cullen limping about the stage.

The producers of the original I’ve Got A Secret used Cullen once or twice as a fill-in host when Moore was away but it was not satisfactory. The nature of the show, with stunts and demonstrations of various contestants’ secrets, demanded a host who could work on his feet. When the ’76 version of the show came about though, it seemed more important to try and recapture the spirit of the earlier series so they decided to have Cullen preside even if that meant limiting the physical segments. It probably seemed like a good trade-off but in the end, it really didn’t matter. Nobody was watching.

Thanks to Kenneth Johannessen for the ticket scan.

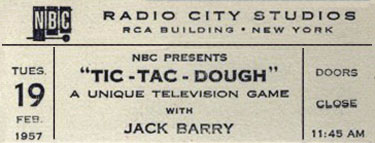

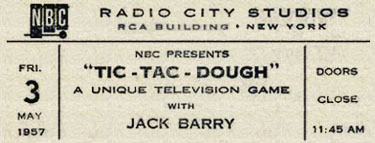

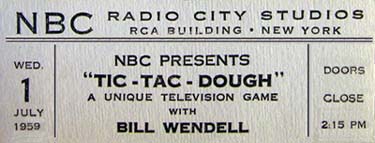

Tic-Tac-Dough (1956-1959)

Tic-Tac-Dough had a long, checkered history. Produced and originally hosted by Jack Barry, it debuted on NBC daytime on July 30, 1956. Barry was busy with his company’s prime-time hit and he eventually handed hosting chores off to Gene Rayburn. Announcing Legend Bill Wendell was the announcer and when Rayburn moved on in 1958, Wendell took over as host, continuing until this run of the show did its final broadcast on October 23, 1959. A prime-time version, hosted by Jay Jackson and later by Win Elliot, ran from September 12, 1957 until December 29, 1958.

What killed Tic-Tac-Dough was the scandal that Barry and his line producer, Dan Enright, were rigging their shows. Most of the outrage was over their other prime-time series, Twenty-One, but there was plenty of evidence that the outcome of many a game of Tic-Tac-Dough was prearranged. In particular, a Tic-Tac-Dough contestant named Kirsten Falke was subpeonaed by a government investigation and she admitted that one of the show’s producers, Howard Felsher, coached her on how to win and gave her answers in advance. The prime-time version was yanked off the air but NBC attempted to keep the daytime version around for a time, swearing that it had been cleaned up and was now on the level. It may have been but audiences stopped watching. Perhaps they didn’t believe that the show was now honest or maybe it just reminded them how they’d been deceived.

But that was not the end of Tic-Tac-Dough. It came back in a daytime version on CBS in 1978 and when that was cancelled, it shifted to syndication where it had a long and healthy run from 1978 through 1986. It then came back again for a brief run in 1990.

How did one play Tic-Tac-Dough? Simple. Two contestants competed, one designated as “X” and one designated as “O,” just as in tic-tac-toe. Each of the nine boxes on a tic-tac-toe grid had a category assigned to it and a player could “win” that box by correctly answering a question in that category. Get three in a row and you win. It was very simple, which perhaps explains the game’s long run.

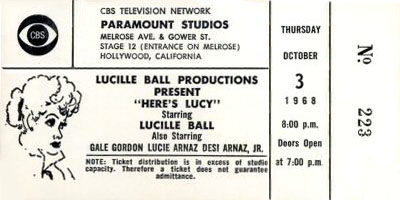

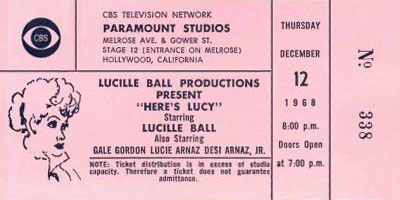

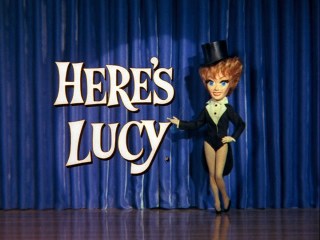

Here’s Lucy

Lucille Ball’s third sitcom, Here’s Lucy, debuted on September 23, 1968, a full six months after her previous series, The Lucy Show, had left the network. One might wonder why the change since her new character, Lucy Carter, wasn’t all that different from her character on The Lucy Show, Lucy Carmichael, and both had Gale Gordon playing the “foil” in her life. Mr. Gordon’s character didn’t change a lot, either, nor did the show’s Monday night time slot. Depending on who you asked, you could get any number of reasons for the conversion…

The old format was tired. After 156 episodes, Lucy needed some sort of change in her show, however minor.

Lucy wanted to work with her kids, Lucie and Desi Jr. Rather than find an awkward way to insert those characters into the life of Lucy Carmichael (which would mean they would not play her children), it was easier to change Lucy to Lucy Carter and just make them that character’s offspring.

Starting a new show would mean that the old show would be freed up for unrestricted syndication and money could be made off those 156 episodes.

Lucy had owned The Lucy Show by virtue of her ownership of Desilu Studios, the company that produced it. In 1967, she sold Desilu to Gulf+Western, the conglomerate which the year before had acquired Paramount Pictures. Lucy didn’t want to keep doing a TV show in which she had no ownership position so she ended The Lucy Show and started a new show which could be owned by her new company, which was co-owned by Gary Morton. Here’s Lucy was produced by Lucille Ball Productions.

And there may have been other reasons as well, but all of the above were probably valid to some extent. How was the new show? About the same as the old show. It had memorable times, like the 1970 episode which guested Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. It had poorer moments, like most of the 1972-1973 season wherein Lucy Carter was in a wheelchair owing to the real Lucy’s leg fracture from a skiing accident. Ms. Ball’s physical comedy was scaled back after that, even after the cast was removed. (They probably would have had to do that even if she hadn’t fractured her leg. Lucy was 61 years old in 1972, a bit aged to be doing some of the things she’d been doing…including skiing when she wasn’t performing.)

Even though Lucy no longer owned the place, Here’s Lucy filmed on the Paramount lot, and the filmings were said to be a love fest to her, with Lucy-loving audiences. Gary Morton often did the warm-ups and gave her the full star treatment, and guest stars abounded. All of Lucy’s old pals — Jack Benny, George Burns, Milton Berle, Phil Silvers, Carol Burnett, et al (even Vivian Vance) — dropped by one or more times. In addition to her kids and Gordon, she was joined in the cast by Mary Jane Croft, who filled Vance’s old function of playing Lucy’s best friend.

The show had good ratings throughout its run and its cancellation (the last one aired March 18, 1974) was met with some controversy. Prime-time TV, especially on CBS, had changed with the coming of shows like All in the Family, M*A*S*H and The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and others that were believed to attract a younger, hipper viewership. Lucy’s act, which hadn’t changed much since the days of I Love Lucy, didn’t seem to fit in. Her “retirement” from weekly television after nearly 23 years was announced as her idea but it was rumored that CBS had the idea first, and that an attempt to place the series with another network had failed. Lucy went on to do guest appearances and specials and even made one return to the world of the weekly sitcom — Life With Lucy in 1986.