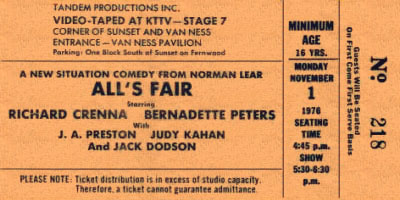

All’s Fair

The premise of All’s Fair — a show which almost no one remembers — was that Richard Crenna played a very conservative political columnist in Washington, and Bernadette Peters played his lady friend who was, of course,very liberal. I only watched a few episodes but it seemed to me — like most political discussions in today’s non-sitcom world — a little too pat, in terms of everyone mouthing knee-jerk positions and coming quickly to realize the flaws in their position. Unlike the real world (except at the residence of James Carville and Mary Matalin), Crenna and Peters usually managed to find a way to resolve or compromise their arguments before bedtime. This show lasted for a year and went through a few storyline changes (and the addition to the cast of Michael Keaton) but it never quite caught on.

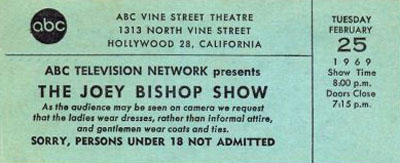

Joey Bishop Show, The (1967-1969)

For decades, ABC and CBS tried over and over to establish a berth in late night television and to compete successfully with Johnny Carson on NBC. In 1967, after giving up on a news-oriented discussion program called The Les Crane Show, ABC dropped Joey Bishop into the time slot with a 90 minute talk show that was pure, Tonight Show-style entertainment. Bishop was a natural choice: He’d served well as a guest host for Carson and for Jack Paar before him. And the public seemed to like him. They’d watched the previous Joey Bishop Show — a situation comedy — in sufficient number to keep it on the air from 1961 to 1965. On it, Bishop played a talk show host so, in yet another case of life imitating art, he became a real talk show host.

Bishop’s new show had many things going for it. Regis Philbin was a fine announcer and sidekick who sometimes managed to steal the spotlight from his boss. Johnny Mann was the bandleader and he gave the show a good sound. The whole thing emanated from Hollywood at a time when Carson was still based in New York. That — and Bishop’s many show biz friendships — seemed to guarantee a steady stream of big name guests, though operating on the West Coast did have one big disadvantage. As you can see from the ticket, The Joey Bishop Show taped in the evening. That meant a one-day delay in being broadcast. With so much in the news, Carson’s monologues and guest chats were becoming more topical and Bishop was lagging a day behind. If as sometimes happens in comedy writing, the same joke occurred to both writing staffs at the same time, Joey would be uttering it twenty-four hours after America had heard it from Johnny.

In fact, the biggest plus Bishop had when his show debuted on April 17, 1967 was that he wasn’t opposite Johnny Carson, who was then engaged in a battle with NBC over compensation and control. Johnny was off the air for several weeks, leaving The Tonight Show to a series of guest hosts — primarily country-western singer Jimmy Dean — and the late night audience to Joey. For a brief time, it looked like ABC was establishing its foothold in the time slot and that may have stampeded NBC into acceding to Carson’s demands, which they did. When Johnny returned to his natural habitat, Joey’s ratings dropped significantly. Thereafter, he trailed and the gap grew slowly wider…not that there weren’t moments when it looked like Joey was clawing his way back. Johnny took a lot of vacations, and they always gave Joey a little bump. And when his numbers dipped and rumors of cancellation began to swirl, Joey could usually manage to land a superstar guest and bring some audience back.

One of his highest ratings came after a taping when Regis Philbin abruptly announced that he was quitting the show. The one day delay worked to the show’s benefit that time. The news spread and much of America tuned in to hear Philbin announce — apparently stunning Joey — that the network had never wanted him in the first place and that he had endured too much criticism from them that he was dragging down the show. A few nights later, everyone watched again to hear Bishop announce that everything had been smoothed over, after which he welcomed Regis back to the show. The incident gave Joey two of the few nights he beat Carson but several TV critics suggested it was all an arranged stunt.

Finally though, ABC had to accept the reality of atrophying ratings. In late ’68, CBS announced that Merv Griffin would host an 11:30 talk show to commence the following March. Recognizing that this would split the already-small audience of folks who didn’t choose to watch Johnny, ABC decided to see if Dick Cavett could succeed where Bishop hadn’t. Sure enough, when Merv went on, Joey’s numbers plunged. Bishop didn’t even host the final weeks of his program, leaving it to guest hosts until it was replaced by Cavett in May. Not long after, Carson enlisted Joey as his main guest host and Joey wound up sitting behind Johnny’s desk 177 times, which was the house record until 1983 when Joan Rivers was named “permanent guest host.” It was a great example of the old show business maxim” “If you can’t beat ’em, fill in for ’em.”

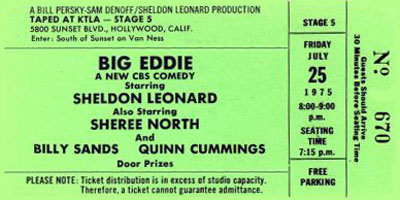

Big Eddie

Sheldon Leonard spent most of his early acting career playing gangsters, race track touts and other shady individuals. In the sixties, he turned to producing and directing but could always make time for the occasional mobster role. In 1975, he even starred in a short-lived situation comedy about a former tough guy. Big Eddie featured him as Eddie Smith…and one suspects the innocuous surname was chosen to make sure there was no connect to any ethnic group. Smith had made the move from the rackets to an almost-respectable life operating a New York sports arena. Past associates and old, unfinished business from his past life had an annoying way of turning up, though all Eddie wanted to live an honest life with his spouse (a former stripper played by Sheree North) and their granddaughter (played by 12-year-old Quinn Cummings, who would go on to steal the movie, The Goodbye Girl, two years later). Eddie also had a thing about bubble baths and could often be found luxuriating in one.

The show went on the air August 23 of 1975 with solid writing/producing from Bill Persky and Sam Denoff, who’d worked with Leonard on The Dick Van Dyke Show among other triumphs. CBS didn’t seem to have a lot of faith in it. After only three broadcasts, they moved it to another night — never a promising sign — and wound up shutting it down after only ten episodes. It was a bad year for Persky and Denoff, who were simultaneously launching a sitcom for NBC called The Montefuscos. They made thirteen of those but the network only aired eight or nine of them.

I remember Big Eddie as a pleasant show that kept hitting the same note over and over…Eddie trying to convince people that he’d changed and had put the old days behind him. I also seem to recall that it was never quite clear how nefarious those old days had been; like early on, the idea had been that he’d been the kind of hood who had people rubbed out but someone — the network or the producers or someone — had said, “No, then he’d be a murderer who got away with it and audiences wouldn’t like him.” So they softened his backstory down to the point where he was almost a businessman who’d occasionally dealt with the wrong people, thereby removing what might have been more interesting about Eddie Smith. Still, it was a nice, albeit short star turn for Sheldon Leonard, who was very good in the role. He didn’t do much acting after that but did manage to get cast as J. Edgar Hoover in a TV-Movie just before he retired. That might have been the sleaziest character he every played.

Lloyd Thaxton Show, The

Lloyd Thaxton was a fixture of Los Angeles TV for much of the sixties, primarily for an afternoon dance party show not unlike Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Thaxton’s had a couple of different names — Lloyd Thaxton’s Record Shop, The Lloyd Thaxton Show, Thaxton’s Show and others — but they were all Lloyd with a bunch of local teens, a few musical guests and a lot of clever games and stunts.

Working with almost no budget in the shabby studios of KCOP, Channel 13, Thaxton came up with ingenious ways to keep viewers interested when all he did was to play current hits and let kids dance to them. Recording artists would come on and lip-sync their records…and I always liked the fact that they usually wouldn’t assume we thought they were playing and singing live. They’d own up to the miming…and if the performer didn’t seem to know the lyrics to their own song, as was sometimes the case, Thaxton would run over and mix up the cue cards to throw them further off. He’d also get up himself and lip-sync to a Bobby Darin or Bobby Vinton record. Teenagers who showed up with tickets like the one above would dance or participate in games but Thaxton would also select some of them to get up and pretend to be Chad and Jeremy or Sonny and Cher or someone and lip-sync to those performers’ hits. Sometimes, Lloyd would take a photo of a singer or an album cover with a close-up of the artist’s face, cut out the mouth area, insert his own lips and “sing” the song that way.

What made it all work was Thaxton himself. He was unpretentious, self-effacing and funny…more than could be said for most of those who went up against him with similar shows. There were a number of them because they didn’t last, while Thaxton went on and on…all the way until around 1968 when all the local stations were getting out of producing their own shows. For the last few years, he was also syndicated and the show did well in other cities, as well. The trouble was that with the rise of afternoon talk shows and stations expanding their news broadcasts, there were no time slots for it. Thaxton moved on to host a few game shows that didn’t last, then moved to the other side of the camera as a producer and writer.

I used to see him in the hallways at NBC when I was writing a show that taped there and he was producing a series with consumer advocate David Horowitz. He always looked so busy, rushing to some meeting or something, that it was awkward to stop him and tell him how much I’d enjoyed watching his show. Finally one day, I approached him and got about six words into what I wanted to say before someone came running down the hall to tell him there was an urgent phone call. He excused himself and ran off and I never got to finish. I thought of calling his office and leaving it on his voice mail but I was afraid he’d just lip-sync to it.

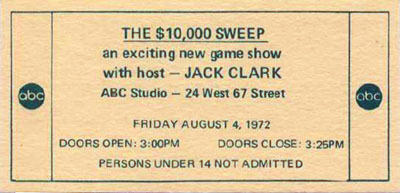

$10,000 Sweep, The

You probably haven’t heard of The $10,000 Sweep because it was an unsold game show pilot. The way it worked, two pairs of contestants competed against one another to answer questions. If a team won one game, they earned $2000. If they won two, they got $4000 and so on, for a total possible winning of a then-staggering ten grand. ABC didn’t buy the show but the notion of giving away ten thousand dollars stayed with producer Bob Stewart who soon sold The $10,000 Pyramid to CBS with Dick Clark as host. Sweep was hosted by another, unrelated Clark — Jack Clark, a frequent game show announcer and an occasional an on-camera host. He passed away in 1988 and probably still holds the record for hosting game shows that didn’t get on the air.

Not only did he preside over an amazing number of unsold pilots but he was one of the first people many producers called when they needed someone to host an untaped “run-through” of a potential program. Many shows go through dozens of such rehearsals and tests before they get anywhere near an actual pilot, and Jack Clark was the guy who — assuming he wasn’t working for pay somewhere that day — would always come over and host your run-through for little or no money. Around 1981, I worked with him on an unsuccessful effort to revive the show Rhyme and Reason in a new format. It led up to a run-through for NBC execs (and went no further) but I was impressed with Clark’s obvious experience and with how utterly cooperative he was. Charlie Brill and Mitzi McCall were the celebrity panelists and though we were doing it just once in a dingy rehearsal hall for an audience of about ten, Clark performed like he was hosting a real TV show on a real set with a full house and all of America watching. A very nice man and, as they say, a true professional.

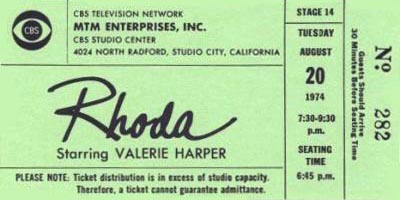

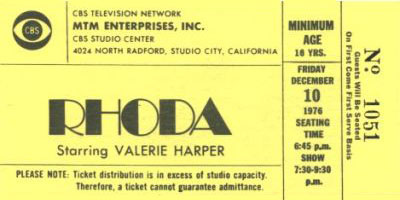

Rhoda

Valerie Harper appeared in (and darn near stole) the first episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1970 and many thereafter. Her Jewish, agonizingly-single character of Rhoda Morganstern provided a nice contrast to Mary’s white bread niceness. And after veteran character actress Nancy Walker began appearing occasionally to play Rhoda’s mother, you had another sitcom just waiting to happen. Finally, in 1974, it spun off on its own, largely under the creative direction of writer-producers Lorenzo Music and David Davis.

Harper and Walker were at the center of it all, joined by Julie Kavner as Rhoda’s younger sister, Harold Gould as her father, and a number of characters who were probably intended as regulars but didn’t stick around long. This included David Groh, who played a man who wooed and eventually wed the title character. Though the wedding episode drew monster ratings, the show lost a great deal of its edge with a married Rhoda. Eventually, they separated and the show never quite regained its pre-marital momentum. In all, it lasted five seasons.

The most interesting character on the show, and maybe the most popular, was never seen. It was Carlton, the perpetually-inebriated doorman of the building in which Rhoda lived — a man heard primarily over that building’s intercom. He did make a few on-camera appearances but something always got in the way, preventing the audience (and even Rhoda) from seeing his face. Carlton was so popular that when Rhoda got married, the producers made sure the newlyweds made their new home in the same apartment house. (One of those producers, Mr. Music, provided the voice of Carlton. In 1980, Carlton was finally seen — in the pilot for what was intended as a weekly, prime-time animated program, Carlton, Your Doorman. The one episode produced won an Emmy as that year’s Best Animated Special but failed to become a series.)

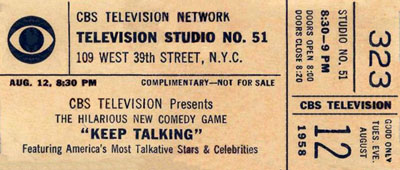

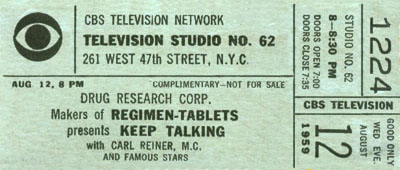

Keep Talking

Keep Talking was a prime-time game show that ran from 1958 to 1960. Each week, two teams would compete, each team composed of three celebrities. The rules changed from time to time but basically, the idea was to keep a story going with the panelists handing it off each time a bell rang, improvising wildly. Somewhere in there, they had to incorporate a secret word and the other panel had to guess the word…and as I recall from my vague memories, no one cared all that much about the scoring. The fun was in how one panelist would take the story off in some odd direction and then the next would have no idea what to do with it. Frequent players included Paul Winchell, Danny Dayton, Morey Amsterdam, Peggy Cass, Pat Carroll, Orson Bean, Audrey Meadows and Elaine May.

The show went on the air in July of 1958 and its first host was Monty Hall, a Canadian who was then fairly new to American TV. He was replaced in October because, if we believe his autobiography, the comedians on the show were complaining about him making funny remarks and competing with them. This seems unlikely, especially since his replacement was Carl Reiner, who was probably funnier than anyone on the panel. When Reiner left to do other things, Merv Griffin took over for the final season.

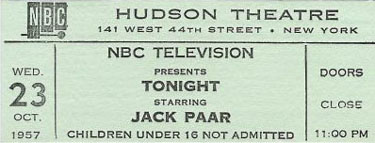

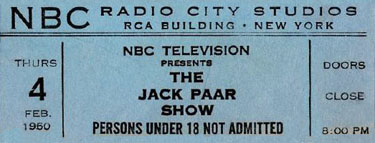

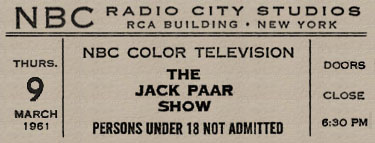

Tonight (1957-1962)

Steve Allen hosted his final episode of Tonight on January 25, 1957. The following Monday, NBC debuted a new multi-hosted, “magazine” show in the time slot…Tonight: America After Dark. It was an instant flop and they hurriedly began searching for someone who could do a new version of Tonight more like the old version. The logical choice might have been Ernie Kovacs, who’d hosted two nights a week during the final months of Allen’s run…but Kovacs was off in Hollywood appearing in movies and therefore unavailable. Instead, they picked Jack Paar, who had hosted a dizzying array of short-lived programs for all the networks in the preceding years. He took over NBC’s late night time slot on July 29, 1957.

The early Paar Tonight program was a mess. At one point before its debut, someone at NBC got the brilliant idea that it should consist of three separate game shows. Each night, the contestant who won the first would move on to appear on the second…and so forth. This notion was discarded, in part because America After Dark was sinking fast and there wasn’t the time to develop three new game shows. So they went with the idea of conversation/chat show but even then, NBC wanted to save a tiny amount of money by booking guests a week at a time — the same people for five nights in a row. This too was discarded but for the initial weeks, Paar struggled to make conversation with eccentric guests in whom he had no interest. Further souring the proceedings was the man selected as Paar’s sidekick, veteran comic actor Franklin Pangborn. Pangborn had been funny in scripted film parts but on a live, ad-lib show he was a disaster.

For several months, Paar teetered on the brink of cancellation but then everything miraculously came together. Pangborn was eliminated and eventually, the show’s announcer — Hugh Downs — expanded his role to full sidekick status. And Paar found his style and the right kind of guest to have on. He soon had a whole stock company of recurring visitors that included Alexander King, Oscar Levant, Dody Goodman, Jonathan Winters, Peter Ustinov, Hans Conried, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Elsa Maxwell, Cliff “Charlie Weaver” Arquette and Peggy Cass.

In these tickets, one can see things changing. Paar didn’t like staying up late — he once said he’d never watch his show if he hadn’t been on it — so when taping became more practical, it went from a live show to one recorded earlier and earlier in the evening. For some reason, as they moved it earlier, they decided to raise the minimum audience age from 16 to 18.

But the big change was in the name. Few recall that there were a few years there when Tonight ceased to exist and it became just The Jack Paar Show, though many people, Paar included, continued to refer to it as “The Tonight Show,” which technically had not yet been its name. It was just Tonight. As you can see from the above ticket for 2/4/60, it was The Jack Paar Show then. Exactly one week later — 2/11 — Paar did his famous on-air resignation because the network had censored an innocuous joke about a “water closet” and what he said when he quit for several weeks was, “I’m leaving The Tonight Show.” Before that, there had also been a brief interim period when its title had been Jack Paar Tonight. (Paar’s unsuccessful attempt to return to the format in 1973 would be called Jack Paar Tonite.) In Paar’s final months, NBC did all it could to get the word “Tonight” back into promotions and TV Guide and to pretend that that had been the name all along.

Paar did his final show in the time slot on March 30, 1962, and the show was handed over to guest hosts for six months to await the arrival of Johnny Carson. After a brief hiatus, he returned to NBC with a shorter but largely identical weekly prime time series called The Jack Paar Program that ran until 1965.

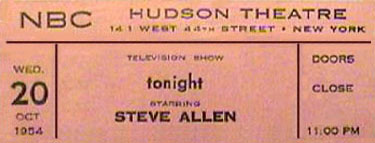

Tonight (1954-1957)

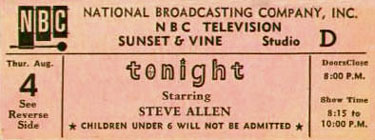

In 1954, NBC exec Sylvester “Pat” Weaver was looking for a show that could open up the late night time slot for network programming. He’d previously tried a raucous variety show there — Broadway Open House, hosted some nights by Morey Amsterdam and others by Jerry Lester. This time, his search led him to The Steve Allen Show, which the New York NBC station had recently begun airing. That show was acquired, retitled and expanded…and it debuted on September 27, 1954 as Tonight! Histories note that the exclamation point was soon deleted…and we can see there is none on the earliest ticket above, which is from October 20.

Tonight did everything it could to fill the time: There were games, interviews, sketches, songs…even, for a brief time, a nightly (real) news round-up. Steve played piano, chatted with eccentric guests and audience members and put up with stunts which he sometimes described as “plots by the staff against my life.” Gene Rayburn was the announcer and sidekick, Skitch Henderson led the band and the regulars included singers Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Pat Marshall and Andy Williams. Allen also developed a “stock company” of talented comedians like Don Knotts, Louis Nye, Tom Poston and Dayton Allen, though some of these didn’t join him until his post-Tonight ventures.

Most of the time, as the above tickets show, Tonight came from the Hudson Theater in New York. The one ticket above for a broadcast from the West Coast is for August 4, 1955. For eight weeks that year, Tonight emanated from Hollywood where Steve Allen was filming the title role in the movie, The Benny Goodman Story. Most performers would consider it a tiring full-time job to either host a late night show five evenings a week or to star in a major motion picture. Somehow, without missing a day on either, Allen managed to do both…though right after, he did take his first two-week vacation from Tonight, turning the festivities over to guest host Ernie Kovacs.

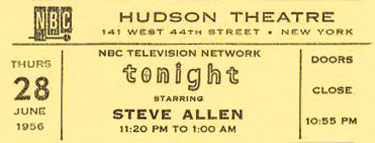

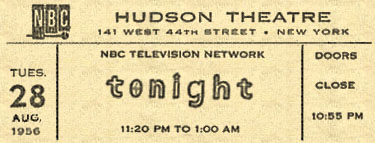

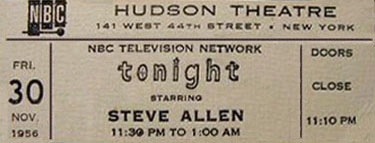

The August 28, 1956 ticket lacks the name of Steve Allen because it was for a Tuesday night. In June of that year, Allen and his crew had added a prime-time Sunday night series to their workload, competing on NBC against Ed Sullivan’s popular CBS program. The burden became too great and soon after, the Monday and Tuesday night broadcasts of Tonight were turned over to a roster of ever-changing guest hosts, including Ernie Kovacs, Jack Paar, Henry Morgan, Bill Cullen, Gene Rayburn, Rudy Vallee, Tony Randall, cartoonist Al Capp and even, from the old Broadway Open House, Morey Amsterdam and Jerry Lester. It is not known who was hosting on the eve of the above ticket, but Kovacs became the regular Monday-Tuesday host in October.

He continued, with Allen hosting the rest of the week, until the end of January, 1957 when Allen decided to give up the late night show. The entire thing was replaced by a famous disaster — a multi-hosted “magazine” show called Tonight: America After Dark. When that didn’t work, they went scurrying to find another single host who could do something more like what Steve Allen had done. The result was the Jack Paar era of Tonight.

The Steve Allen years remain legendary but largely lost: As with many shows of the day (including the Tonight run of Paar and the early years of his successor, Johnny Carson) few tapes or kinescopes exist. Allen went on to do more shows, some of which were in a similar enough format that many people remember them when they think they’re remembering his years on Tonight. This can get you to wondering if the lost shows are legendary in part because they are lost, and are appraised only through rose-colored memories. Judging from what does exist — and from those later shows — that’s not the case here. Steve Allen’s Tonight does seem to have been as unpredictable, spontaneous and innovative as everyone remembers…the kind of show you dared not miss because the next day, everyone would be saying, “Did you see what happened on that show last night?” Talk shows aren’t like that anymore. They don’t have anyone as brave and as willing to soar before millions without controls and preparation as was Steve Allen.

We do have a mystery with these tickets. Every single history of Tonight says that for its entire run, the Steve Allen version was an hour and 45 minutes in length, commencing at 11:15 PM in the East. Yet here, we see that the 6/28/56 and 8/28/56 tickets give an airtime of 11:20 PM to 1:00 AM, and the 11/30/56 ticket says 11:30 PM to 1:00 AM. If there’s an explanation for this, I’d love to hear it.

Steve Allen Show, The (1953-1954)

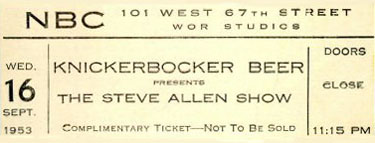

In 1953, the local NBC station in New York was WNBT and its late night movie program was getting clobbered by a better package of films being broadcast every night on the CBS affiliate, WCBS. Knickerbocker Beer, which was then a major brand, decided it wanted to sponsor something else on WNBT…say, a variety show. Ted Cott, a successful radio executive who had recently moved into television at the NBC affiliate, suggested Steve Allen as host.

Histories say that Allen debuted in the Fall of ’53 with a 45 (or 40 in some accounts) minute program every night called The Knickerbocker Beer Show, and that after thirteen weeks, its name was changed to The Steve Allen Show. The above ticket suggests that the name change came much more rapidly than that.

Done at first without writers and always without much of a budget, Allen’s local show was an immediate success, garnering both critical acclaim and the desired higher (than WCBS) ratings. On it, Allen would play the piano, chat with audience members or guests or sidekick-announcer Gene Rayburn, bring on Steve Lawrence and/or Eydie Gorme to sing a song — the bandleader was Bobby Byrne — and basically lay the foundation for talk shows to come. Less than a year later, most of the operation would be moving over to do a network show called Tonight.